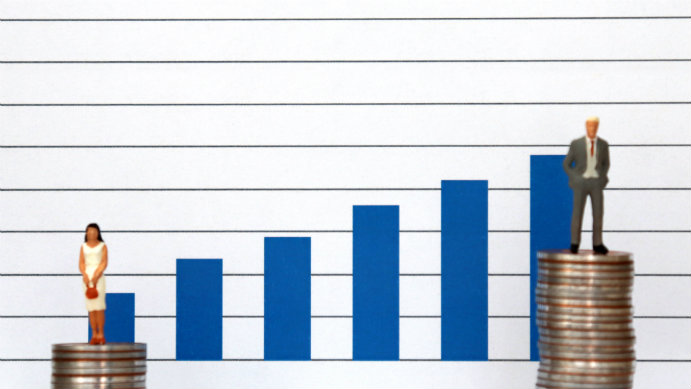

The gender pay gap in the United States persists across all demographics and industries, according to the American Association of University Women (AAUW), a leading voice in promoting equity and education for women and girls.

The organization’s fall 2018 edition of its report The Simple Truth About the Gender Pay Gap, states that women, no matter their age, state of residence or profession, continue to get paid less than men, even in female-dominated professions such as nursing.

“Some attribute the pay gap to perceived gender differences in wage contract negotiations,” says Holona Ochs, associate professor of political science at Lehigh University, “or, to a belief that women undermine their own bargaining position by extending too much trust to others in negotiations.”

In other words, some perceive men as more effective negotiators than women and assign this as a factor to explain the wage gap, in whole or in part.

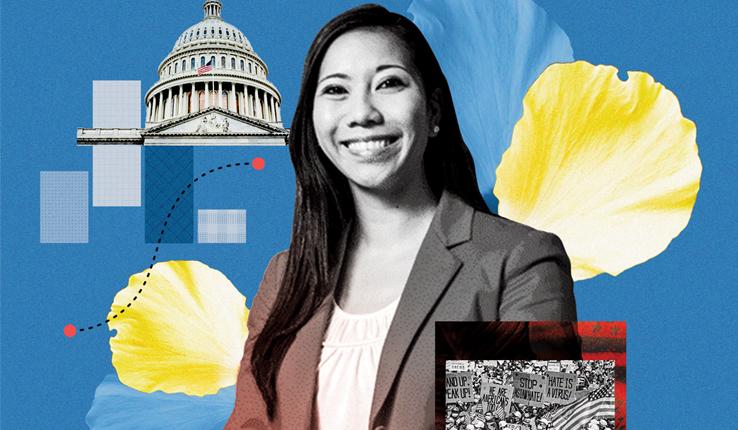

The findings from a new study, co-authored by Ochs, suggest that these notions are misleading. The study is described in a paper called “Experimental tests for gender effects in a principal-agent game.” It is co-authored by Andrew B. Whitford, professor of public administration and policy at the University of Georgia and appeared online yesterday, January 8, 2019, in the Journal of Behavioral Public Administration.

It is the first study to look at gender differences in trustworthiness and perceptions of benevolence in the context of hierarchical negotiations, such as wage-labor agreements. And it finds that women and men reach very similar negotiations outcomes in a neutral setting. In the paper, the authors apply their findings to the public administration sector, though it is relevant to industries across the board.

“Our findings suggests that the gender stereotypes that lead to the perception that men may negotiate better wage contracts than women are misleading, and that individual behavior in hierarchical negotiation settings like between a boss and employee — is more likely affected by the context, than by gender differences,” says Ochs.

The authors write: “...our research report shows how institution-free environments (like experiments) which do not exist in the real world – provide a baseline to measure how institutions shape the behavior of real public workers in real agencies.”

Ochs and Whitford conducted experiments in which people randomly assigned to the role of principal (boss) and agent (employee) negotiated a wage labor agreement that determined the payment each received for their participation. Participants were also administered surveys to assess perceptions of generosity, trust, trustworthiness, and negotiation strategies.

An analysis of the data reveals that:

- Women do not obtain negotiated outcomes that are significantly different from men, indicating that persistent wage differences between women and men are not due to differences in the contracts negotiated.

- Women are not necessarily more generous than men and are equally motivated toward self-interested behavior in economic incentives.

- Women are no more or less trusting than men of their superiors or subordinates.

Women are more likely to be extended trust, and the likelihood that women extend trust to men is not significantly different from that of men.

“The data and tests we report suggest that stakeholders pay attention to the broader institutions that shape opportunities for and constraints on women as the context is more important for achieving equity than focusing on negotiation skills,” says Ochs.