Creating the bronze castings for all the pieces was a complex process, explains Heiss. First, the objects were 3-D modeled and files were sent to be printed in wax at an industrial prototyping facility.

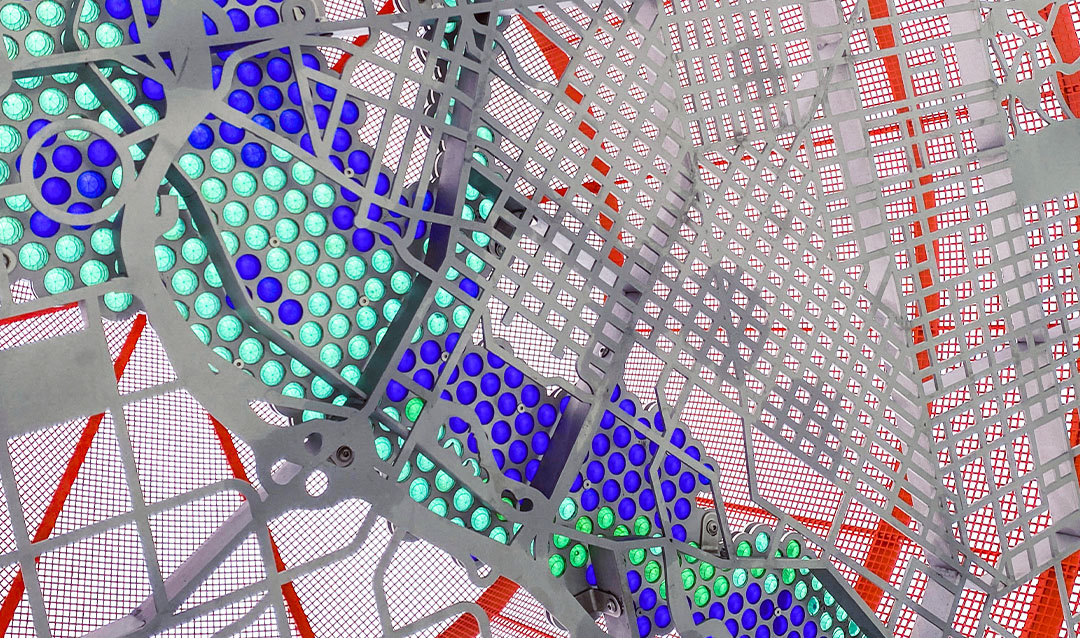

“We had to go through a commercial prototyping process rather than just carving objects like a traditional sculptor as the inside turned out to be just as important as the outside,” says Heiss. “Normally, with a bronze casting process, you sculpt the object out of clay, make a mold of that, cast a wax duplicate of the original, coat the wax version in ceramic material and then pour molten bronze inside the ceramic shell-burning out the wax. What you end up with is the bronze cast where the outside of the object may be correct but the inside is either solid or an uncontrolled shape. We needed the inside of the object to precisely fit the optical components, and it turned out companies that prototype things like bronze plumbing fittings could help us where artist foundries couldn’t.”

When people look through the various instruments, they see a combination of the current streetscapes and an overlay of some historical aspect of the site. For example, looking through one of the objects, one sees the streetscape of a town square as it is now overlaid with an image of a woman walking a tightrope between two of the buildings, an event that occurred there in 1805.

“What I love about these projects is that the more time you spend in a place looking for what makes a place special, the more you find that just about anywhere in the universe has an overlooked story to be found,” says Heiss.

Though public art seems like a natural match for Heiss’ background as an architect, it is not where his art career began.

“If, 15 years ago, you were to say ‘public art,’ I might have cringed,” says Heiss. “Those two words sound evocative of nothing I would want to be a part of and remind me of large ego-driven sculptures dropped off in public spaces that no one seems to care about or understand. But now I seem to have slipped into this practice as I have most of my career: from the side.”

Still, Heiss relishes the accessibility that public art offers, interactions that occur even before a piece might be installed. For example, one night, before being loaded onto a truck headed for Denver, one of the huge Markers sculptures sat on a street outside Heiss’ downtown studio in Allentown, Pennsylvania, attracting the attention of a local police officer who inquired what Heiss was doing. Heiss got nervous. Did he need a permit? Was he blocking the sidewalk? A conversation ensued and the officer revealed that he was simply interested in the art.

“Turns out he’s a really good artist and takes amazing photographs,” says Heiss. “I ended up talking with him for an hour. It’s really exciting to be in the city and actually engaging with it rather than just being holed up in a studio where nobody knows what’s going on. Curious people stop in to the studio all the time. Sometimes that slows the creative process down, and sometimes, those conversations are the process.”

It is the interactivity, the making of art that is a part of people’s daily lives that seems to attract Heiss most of all to this work.

“It’s hard to predict what anyone will get out of a work of art,” says Heiss. “As an artist, you put things out in the world, and what they become is dependent on those that interact with them. The work always takes on a life of its own, but I hope by engaging the community in the process and focusing on local stories, places and people, these projects end up meaning something to those who see them most.”

Wes Heiss is a designer and visual artist whose work explores humanity’s relationship with technology. He earned his M.Arch from Rice University and his bachelor’s in architecture and ceramics from Bennington College.