Krepps wasn’t sure what she wanted to focus on until a meeting with Bill Hunter, director of the Office of Fellowship Advising. He referred her to his wife, a food scientist for Mars Incorporated. She switched from environmental science and electrical engineering to a biochemistry path. Sabrina Jedlicka, associate dean for academic affairs for the engineering college, connected her with Snyder and Schultz.

“I’ve always been interested in food. Food was really important for my family growing up—that was where we decompressed at the end of the day. Food is a really important part of how we socialize,” says Krepps.

“My mom has always loved to cook. When I was born and she decided to stay home, she watched the Food Network. Ever since I was old enough to be safely in the kitchen, she taught me how to bake and cook. That’s how we bonded.”

Krepps had never heard of cultivated meat before the research opportunity was presented.

“It sounded very strange. It still kind of sounds pretty futuristic when you describe it,” she says. “Even in the scientific community, it is still a very new subject.”

Krepps read some of Schultz’s and Snyder’s research and says, “It makes a lot more sense to me now.”

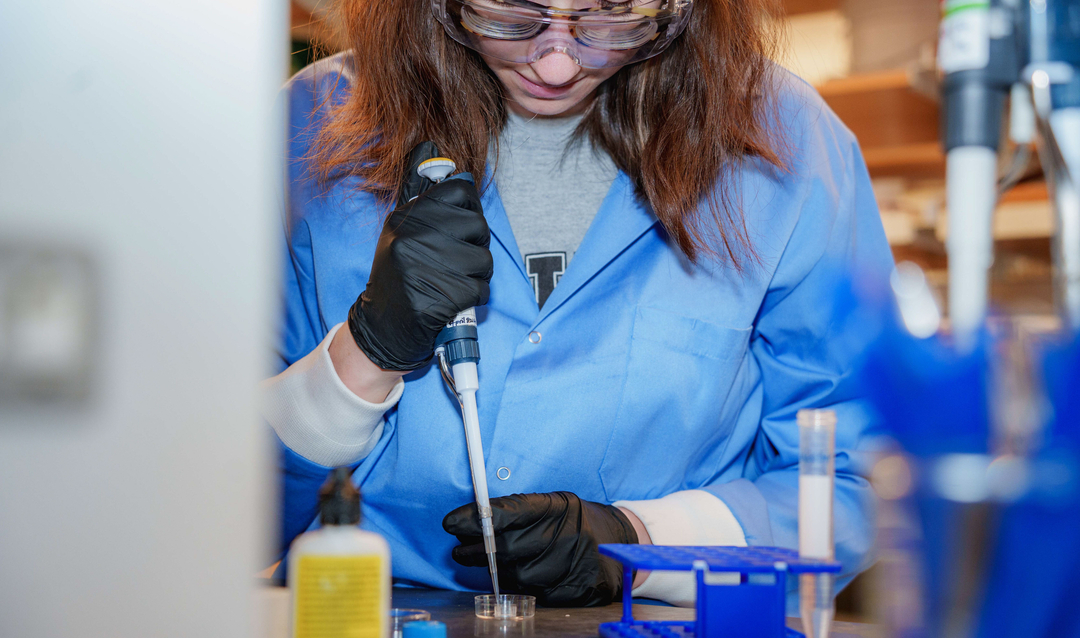

Krepps has been working in the labs since last June. Her job is to make long, thin molds in different shapes. This is done to mimic confinement that cells experience in the native muscle environment. By mimicking this environment she hopes to be able to measure the formation of fiber structures by the cells, which is similar to the structure of animal muscle or meat. She designs the molds, which are created by a 3D printer. Krepps polymerizes hydrogels into the molds. Fluorescent probes are then injected into the scaffold to characterize the material. The probes are easy to see through a microscope as they move. Ultimately, cells will also be incorporated. Krepps expects to perfect her mold making and gel fabrication skills enough to advance to working with living cells this summer.

It’s all very meticulous and laborious. Krepps had never done lab work and had to learn many new skills, including using the equipment, storing the materials and samples at appropriate temperatures, operating a microscope, taking images and analyzing the results.

“There’s a lot of technique that needs to be used so you don’t contaminate or kill the cells,” she says.

Schultz says Krepps’ work is a huge piece of the research puzzle that could lead to the development of real, tasty meat at prices affordable to the average person.

“We really don’t have enough of a fundamental level of understanding as to how cells behave in confined narrow spaces so we chose the long, thin shape because it’s similar to muscle fiber. Once we have a general understanding of what cells do in that environment, then we would be able to ask more complex questions,” she says.

Krepps will continue the project through her graduation in 2024 with a bachelor’s in Integrated Degree in Engineering and Arts & Sciences. In April, she presented at the IDEAS symposium. She also will present her findings at the 2024 David and Lorraine Freed Undergraduate Research Symposium.

“I think most likely the career I am looking into has a large research component and the scholarship is an amazing step of getting to that place,” she says. “Probably something in food science, something with a tangible impact—that’s very important to me. I like to be able to see that what I’m doing has a positive effect somewhere.”

--Story by Jodi Duckett