“Her husband, for example, would show up when they were separated,” explains Dolan. “He would see she had a book coming out, he would show up at the publisher, and say, ‘Okay, pay up.’ And it was his legal right. So she solved that problem by sending the publisher her butcher bills, her coal bill, et cetera, so she was always in debt with the publisher. When Benjamin turned up, there was no money. She always owed the publisher. It was genius.”

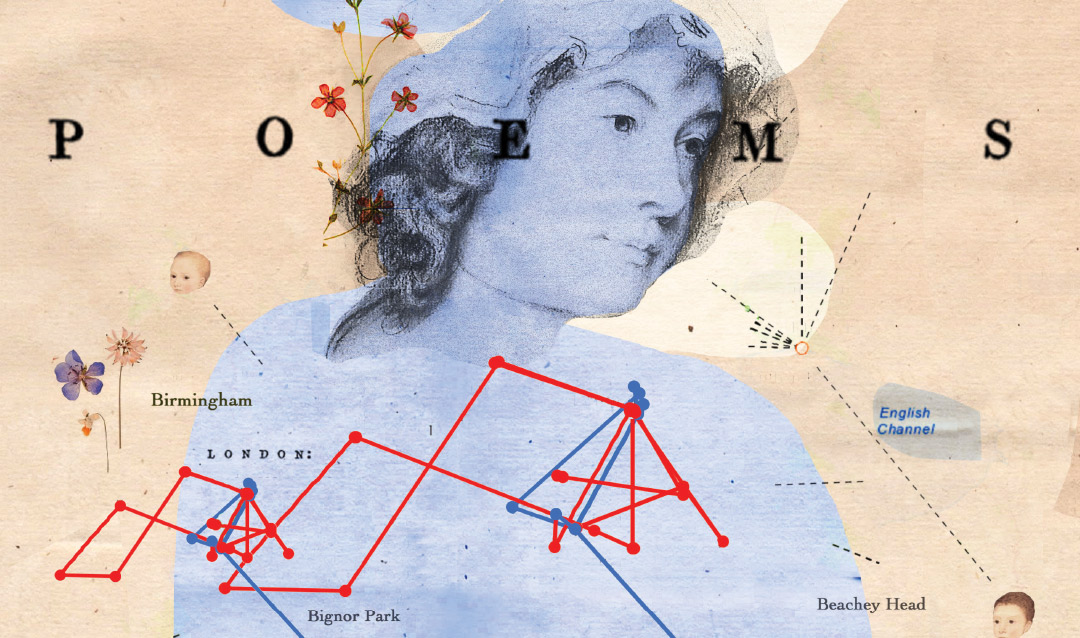

Smith’s strength and resolve caught Dolan’s attention. For example, she says, letters Smith wrote indicate that when Smith was writing Beachy Head, her complex 731-line blank-verse poem, she was dying of uterine cancer, her hands gnarled from rheumatoid arthritis.

“She could barely write or walk, but she wrote this beautiful, life-affirming poem,” says Dolan. “It’s incredible.”

Uncovering Life Stories

In her current project, funded by a Faculty Innovation Grant, Dolan follows the breadcrumbs of Smith’s children’s lives, whose paths reveal much about their mother as well. Dolan finds their life choices interesting, particularly in terms of race and class. For example, one son, Nicholas, moved to Persia and married a Persian woman. The pair sent their mixed-race children to England to be educated by Smith—a move some at the time might have considered unusual, Dolan says.

Although Smith was unable to provide her children with the gentry-class education she wanted for them, several found success. Two sons joined the East India Company and three joined the British Army. One son, Sir Lionel Smith, became governor of Barbados and the Windward Islands, and later of Jamaica after the passing of the Abolition Act, where he was tasked with bringing about an end to slavery in the region.

Dolan visited the National Archives in London, where she read all of Lionel Smith’s letters.

“Their lives unfold in the early British empire, and it’s interesting to me how Charlotte Smith’s financial struggles as a woman and a mom pushed her sons into the empire. They became empire makers because that was their best option. That’s just an interesting dynamic by itself,” Dolan says.

Not as much is documented about Smith’s daughters. One went to India in search of a husband, but contracted malaria and returned to lead a difficult life. The courage it took for her to make that trip in the first place, says Dolan, indicates that Smith’s daughter likely shared her moxie.

“To take that 16-week boat ride to India—that takes guts,” says Dolan.

Dolan has followed where letters and historical documents have taken her, and, as a result, the stories of peripheral characters have surfaced. Dolan has written articles about each.

“Along the way, reading Lionel Smith’s letters in Belfast, Ireland, I found this amazing document written in Arabic and addressed to Lionel Smith,” says Dolan, who worked with a scholar at Purdue University to translate it. “It turns out that it’s an address to Lionel Smith by an emancipated Muslim slave, thanking Smith for his role in emancipation. The letter writer, Mohammad Kaba Saghanughu, used the occasion of emancipation to tell his own life story and enter it into the imperial record. That’s really, really neat.”

Another, a slave owned by the Smith family in Barbados, appeared repeatedly in documents in the Barbados National Archives.

“The way the deeds and letters mentioned Fibbah was different than references to other enslaved people, and so I traced her through the record as far as I could get,” Dolan explains. “This woman’s name just kept coming up. … She was protected from a sale, and then she was willed to one of the sons. It was strange. And so I think … her children might have been Benjamin Smith’s father’s children. … I don’t know. But she had some kind of special status. … She was mixed race, as were her children. I just got curious about her.”

In a way, Dolan says, she sees her work as allowing people who might be left silent by history to be heard. From Charlotte Smith to her children to those whose lives were touched indirectly by Smith’s legacy, Dolan is unearthing stories that might otherwise go untold.

“To be able to follow that curiosity, it is the biggest privilege. I love that part of this work.”