“The new part is that this isn’t in the literature,” she said. “In our line of work, we get asked questions about contemporary Native identity all the time, and we can respond based on our experiences working with Native communities, but it’s hard to find something in the literature to cite.”

Hilary Weaver, professor emeritus at University of Buffalo, said in a review that the book “makes an important contribution to a literature of Indigenous identity that had previously been primarily theoretical or grounded in personal experience without systematic organization or analysis.” The book, she said, presents “a clearly articulated multitude of voices describing complex, nuanced, and sometimes contradictory perspectives on Indigenous identity.”

For researchers in American Indian studies, questions of identity pervade grant applications, data sources and decisions about who qualifies as “Native” for the purposes of research. Some reviewers request that study participants’ Native identity be validated through the use of tribal enrollment cards or Certificates of Degree of Indian Blood.

The Daleys disagree with these methods, seen by many as antiquated relics of colonization. In no other contemporary ethnic group is an individual required to “prove” their identity in these ways, they say.

Rather, they have relied on Native self-identification in their participatory research projects, including the Native 24/7 study on which the book is based.

“There is no question that can be asked that tells you if your participants are really Native,” the authors write. “There is no scale that can adequately measure Indigeneity because there is no one way to be Indigenous.”

Beginning with a “convenience sample” of participants known to the researchers, the study used a “snowball” strategy, through which participants helped recruit others in their social networks. In addition, researchers conducted interviews and surveys at a variety of events affiliated with Native communities.

Interviews were conducted by Native members of the project team, which helped establish rapport with participants and achieve a depth and breadth rare in contemporary studies of Indigenous communities.

Ultimately, study participants represented broad diversity within the Indigenous community, including geographic location, race, enrollment in a federally recognized tribe, and experiences being raised on or off of a reservation or tribal land.

The Daleys, who do not identify as Native, have worked with Native populations for almost 30 years. In addition to conducting research with Lehigh’s Institute for Indigenous Studies, the Daleys co-direct the American Indian Health Research and Education Alliance.

The book comes at a critical inflection point. Between 2010 and 2020, the U.S. Census Bureau reported an 85% increase in people identifying as American Indian and Alaska Native, coinciding with a national reckoning over the country’s treatment of people from minoritized racial and ethnic groups.

Examining identity through several different components, including culture and history, family and community, religion and spirituality, and the politically charged concepts of blood quantums, stereotypical imagery, and ethnic terminology, the book illuminates a wide range of viewpoints informed by participants’ own experiences.

While highlighting several relevant trends that emerge from the data, the authors stop short of drawing broad conclusions regarding collective Native identity or along particular demographic lines. Rather, the book aims to provide space for individuals to describe in their own words the most important facets of their Native identities.

“We decided that the most important information in these interviews and surveys was tied to the words of our participants. We did not want to reduce their views on their own identities into a mere statistical measure,” the Daleys write.

Respondents used a wide range of terminology in describing their own ethnicities, 755 by the authors’ count. Preferences included an array of collective terms such as “Native American” and “American Indian” as well as specific tribal names and various combinations of terms.

Interviewers first asked respondents how they prefer to be addressed, and used that terminology throughout the rest of each interview. In recognition of that diversity, both the book and this article use a variety of terms in referring to the individuals who participated in the research.

“Clearly, the question of what to call people whose ancestry lies in Pre-Columbian U.S. territory is not a simple one and not one that can be answered with a single study on preferences. The heterogeneity of what people want to be called is an indicator of the complexity of identity,” the Daleys write.

While the book will benefit the broader public’s understanding of the complexities of Native identity, it also specifically aims to inform policymakers’ and other researchers’ approaches to understanding Native cultures.

“At last! A detailed report illuminating the demographic, geographic and cultural characteristics of the diverse category of tribal citizens and non-citizens who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native,” said Eva Garroutte, research professor of sociology at Boston College, in a review. “Grounded in many hundreds of qualitative and quantitative interviews, this welcome addition to the research literature also invites its participants to discuss what lies behind their shared identity assertion.”

Christine Makosky Daley is a professor and chair of community and population health at Lehigh whose primary area of research interest is reducing American Indian health disparities. She is co-director of the American Indian Health Research and Education Alliance, a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization dedicated to improving health and educational attainment in American Indian communities through quality participatory research and education.

Sean M. Daley, an associate professor of community and population health and director of the Institute for Indigenous Studies at Lehigh, is an applied sociocultural anthropologist and ethnographer whose research lies primarily at the intersections of religion, spirituality and health. He has also worked in the areas of Native law and policy, identity, education and the environment.

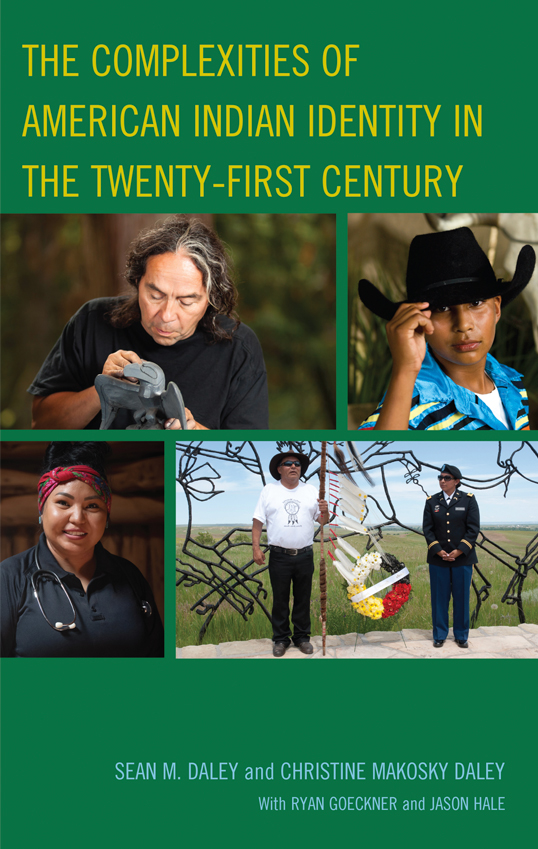

The book was authored with Ryan Goeckner and Jason Hale. The research team included Charley Lewis (Paiute/Navajo), a senior research scientist in the Institute for Indigenous Studies; and Joseph Pacheco (Quechua/Cherokee), an assistant professor in Lehigh’s Department of Community and Population Health and faculty member in the Institute for Indigenous Studies.

Story by Dan Armstrong