When seeking answers to societal questions, the old adage implores investigators to follow the money. But where has that approach led researchers examining why different countries experienced widely differing COVID-19 mortality rates?

So far, in some different — and perhaps contradictory — directions, according to Todd A. Watkins, professor of economics and executive director of the Martindale Center for the Study of Private Enterprise at Lehigh University.

"Studies specific to COVID-19 health outcomes reveal major inequalities among population groups and identify key contributing factors including poverty, lack of household resources, affordability of prevention measures, and limited access to various health and social services," Watkins said. But teasing out the impacts of various economic measures is “an interesting and remaining puzzle in this literature.”

It would track a basic logic that countries with more money and more developed economic systems would see better health outcomes during COVID-19. In some cases that logic has held true. However, studies on some specific money-related matters point to opposite conclusions.

Wealthier Nations Not Better Equipped to Combat COVID

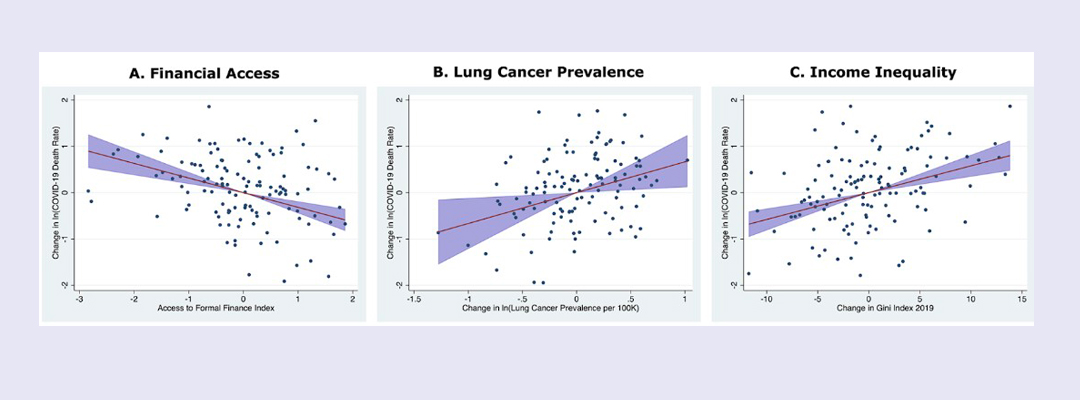

For example, income inequality has consistently proven to be a strong predictor of inequitable health outcomes during COVID-19. As might have been expected, nations with higher degrees of income inequality experienced significantly higher COVID-19 mortality rates. (Those with income inequality one standard deviation above the average level would have roughly 40%-50% higher mortality rates, according to Watkins’s study.)

Yet nations with greater per capita income did not experience a reduction in COVID-19 mortality, as might have been expected. In fact, studies have indicated that the opposite is true.

In both Watkins’ study and previous studies by other researchers, nations with higher per capita income had significantly higher mortality rates, even after controlling for characteristics associated with wealth, like aging, obesity and health care infrastructure.

“Our assumption as economists would be that wealthier nations should have been able to deal with COVID better than poorer nations and poorer populations. And the opposite has turned out to be true in regard to GDP per capita,” Watkins said. “Clarifying what drives this counterintuitive correlation has so far been frustratingly difficult and remains a work in process.”

Creative Inquiry Undergraduates Contribute to Findings

With the help of five undergraduates in Lehigh’s Data for Impact Summer Institute (D4I) and supported in part by the Martindale Center, Watkins sought to add another missing piece to the pandemic-finance puzzle: determining the effects that access to formal financial services such as savings, credit and money transfer services had in relation to COVID-19 mortality rates.

The D4I program is a 10-week Mountaintop Summer Experience facilitated by the Office of Creative Inquiry. In it, Lehigh undergraduate students work with faculty members and external partners to learn data science and practices and apply them in interdisciplinary projects with aspirations for contributing to sustainable impact.

Under Watkins’ guidance, undergraduate students in computer science, statistics, management and economics collaborated to build a database containing data on COVID-19, health outcomes and a variety of economic measures from 142 countries.

COVID-19 mortality data came from Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Systems Science and Engineering. To measure access to and use of formal financial services among countries, the team developed financial inclusion indices using metrics from the World Bank’s Global Findex Database. Data for several other variables came from the United Nations, World Health Organization and the World Bank.

They then ran a number of statistical analyses to discover relationships in the complex web of data points.

The results were surprising even for Watkins, whose past research has focused on the effects of microfinance, fintech and inclusive financial services for the poor.

Access to Financial Services Linked to Reduced COVID Mortality

Access to formal financial services (such as having an account at a financial institution, having a credit or debit card, or having received loans from a financial institution) had a strong reductive effect on COVID-19 mortality rates—as strong, in fact, as the effect income inequality and several known comorbidities had on increasing COVID-19 mortality rates.

“The reduction is surprisingly large, similar in magnitude to, but opposite in direction from, the mortality risks associated with higher rates of lung cancer and hypertension,” Watkins said.