Titanocene Complex Reduces Carbonyls to Alcohols

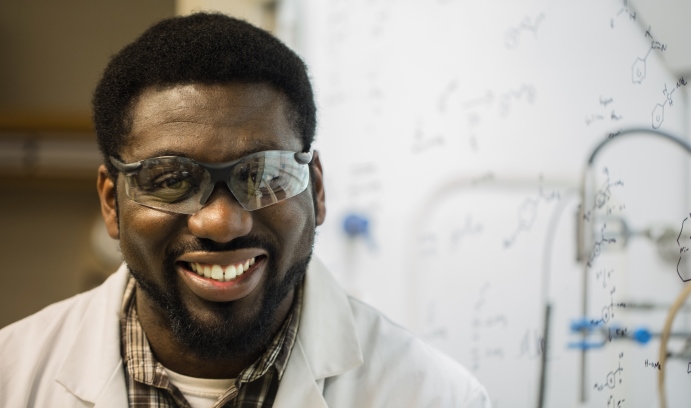

Godfred Fianu, who successfully defended his Ph.D. thesis in August, developed a method of carrying out simple reductions of carbonyls such as ketones and aldehydes to obtain alcohols. (Photo by Christa Neu)

Last August was a memorable month for Godfred Fianu. In the space of two weeks, he defended his thesis, earned a Ph.D. in chemistry and published the cover article in Catalysis Science and Technology, a journal of the Royal Society of Chemistry.

The article described the successful efforts by Fianu and his group to develop and test a new way of catalyzing a critical reaction that produces alcohols in aprotic media. Titled “Catalytic carbonyl hydrosilylations via a titanocene borohydride–PMHS reagent system,” it was coauthored with Kyle C. Schipper ’18, a chemical engineering major, and Robert A. Flowers II, professor of chemistry and Fianu’s adviser.

The cover image for the August issue of Catalysis Science and Technology was designed by Christopher Herrera, a graphic artist in the College of Arts and Sciences.

In the article, Fianu described how he and his group used catalytic titanocene (III) borohydride (titanium bound to two cyclopentadienyl [Cp] ligands and borohydride), in concert with a stoichiometric silyl hydride to carry out simple reductions of carbonyls such as ketones and aldehydes to obtain alcohols.

“Titanium as a transition metal has a number of oxidation states,” says Fianu. “I studied titanium complexes in the plus-3 oxidation state, which are known to react with epoxides to facilitate radical transformations. With this radical chemistry, you can make complex molecules fairly easily under mild conditions and get desired products.

“One of the main focuses of my work is to study reactions that are sustainable and preferably atom-economical as well. That’s what I was looking at with reactions catalyzed by titanocene (III) complexes.”

The project began when Flowers asked Fianu to develop a method of reducing carbonyls to alcohols using a titanocene reagent. It was up to Fianu to determine which of the many existing titanocene reagents could best facilitate the reduction.

Previously, Fianu had been studying the mechanism of a titanocene chloride-catalyzed opening of amino-epoxide derivatives to form indoles, which are basic structures found in a number of natural compounds.

“We did a lot of good work in that area and published really insightful articles,” says Fianu. “Dr. Flowers said, ‘Great, let’s see if titanocene chloride can reduce other functional groups such as carbonyls as well.’ It turned out that the titanocene chloride complex was not very efficient at reducing carbonyls to alcohol so I started digging to see what other titanocene complexes could do that.”

Fianu experimented with many titanocene-based reagents in hopes of finding one that could effectively reduce carbonyls to alcohol.

“We were trying to get things to work with a titanocene reagent because its precursor, which is titanocene dichloride, is readily available and cheap. A lot of our focus was to see what we could do with that particular precursor.”

In several months of research, Fianu met with many frustrations.

“A lot of the reagents that we thought should work, conceptually, did not pan out the way we’d hoped. We had to fine-tune our system and figure things out. Sometimes in research you hit a dry spell and nothing seems to work, and you’re left wondering if anything is ever going to go right. During these times, Dr. Flowers was very supportive. He encouraged me and gave me time to figure things out.”

Fianu finally determined that titanocene borohydride was the reagent capable of most effectively reducing carbonyls to alcohol.

“It turns out that if you use a different reagent to activate the titanocene dichloride, you get titanocene borohydride, which catalyzes the reduction of carbonyls to alcohols. Prior to our experiments with titanocene dichloride, [other researchers] would react it with a metal reductant like manganese or zinc and get a titanocene (III) chloride. And that’s what we were using to open epoxides and to do other chemistry.

“We learned that if you react titanocene dichloride with sodium borohydride, you get titanocene borohydride, which is an effective catalyst in the reduction of carbonyls to alcohols.”

In short, Fianu says, he and his group developed a new method which uses a relatively inexpensive and readily available titanocene dichloride precursor and which can be employed by industries that require the production of alcohols in aprotic media.

In his research, Fianu used several state-of-the-art instruments to determine the mechanisms and pathways of reactions. One of these was ReactIR, an infrared-based system that monitors the progress of a reaction in real time while providing specific information about the reaction.

“ReactIR allows you to see what’s happening during a reaction by monitoring the changes in vibrations of the molecules as the reaction is occurring,” Fianu says.

Fianu also used Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and SpectroVis, a portable visible light spectrophotometer with fluorescence capabilities.

Fianu, who grew up in Ghana, earned his bachelor’s degree from Principia College in Illinois before enrolling at Lehigh. His sister, Cynthia Fianu-Velgus ’08 M.S., is a research scientist in Lehigh’s chemistry department.

Since completing his Ph.D., Fianu has taken a position teaching chemistry at Moravian College in Bethlehem.

He says he is very happy with the education he got at Lehigh.

“I got a wide variety of experiences at Lehigh. I worked with a lot of people and learned the importance of knowing who to go to for help. When you’re an undergraduate student, you have a syllabus, you have a textbook, you have exams, you pass them, and you’re finished.

“As a graduate student, you have to figure out what’s happening, why it’s happening and who to talk with to help you understand.

“Lehigh has been a good experience for me. I am blessed to have an adviser, Dr. Flowers, who really cares about the success of his students.”

Story by Kurt Pfitzer

Posted on: