The governors and the feds

The state capitol building in Montgomery, Alabama. The state’s governor, Robert J. Bentley, turned down an expansion of federal Medicaid funding provided by the Affordable Care Act. (Photo courtesy of iStock/mj0007)

Each of America’s 50 states depends on federal funding to support part of its budget. Using data from the 2012 U.S. Census, a nonpartisan public policy organization named State Budget Solutions calculated that state governments that year received an average of 31.6 percent of their general revenue from the federal government. Mississippi topped the list at 45 percent, while Alaska, with 20 percent, received the smallest amount of federal support.

It makes sense then that states utilize lobbyists to advocate for their interests at the federal level, usually related to funding and regulatory flexibility. Today, about half of all states have lobbying offices in Washington, D.C. In addition, governors are represented by their own national, partisan and regional associations.

What role do these lobbyists play?

Jennifer M. Jensen explores this question and more in The Governors’ Lobbyists, a book scheduled to be released later this month by the University of Michigan Press.

Jensen, an associate professor of political science, studies state politics and intergovernmental relations, interest groups, and political careers. She has worked in Washington in the House of Representatives and as an energy lobbyist.

Drawing on quantitative data, archival research and more than 100 interviews, Jensen details the political development of state advocacy organizations. Among these are the seven associations representing state governors: one nonpartisan group, the National Governors Association; two partisan groups, the Democratic Governors Association and the Republican Governors Association; and four regional ones, the Western Governors Association, the Southern Governors’ Association, the Coalition of Northeastern Governors and the Midwestern Governors Association.

One of the topics that fascinate Jensen most is the growth of these groups, particularly as the political landscape has become increasingly partisan.

“During the last eight years, for example, the Obama administration has had a hard time getting things done in Congress,” says Jensen. “This is one reason why interest groups that lobby officials and make campaign contributions are turning to governors and state policymaking.

“This in turn has helped fuel fundraising by the Republican Governors Association and the Democratic Governors Associations. Both the RGA and the DGA used to be much smaller, and they didn’t focus on fundraising. Now they are the largest state-focused 527 organizations [political advocacy groups with 527 tax-exempt status] in the country.”

Adds Jensen: “Governors have also become more ideologically divided in recent years, making it more difficult to get things done as a group. For example, in recent years, some Republican governors in particular have grown increasingly dissatisfied with the National Governors Association. There has been some exiting with feet.”

Proliferation and division

As Jensen investigated the growth of individual state offices and governors associations focused on federal advocacy, a story of proliferation and, at times, division emerged.

The first state to have a lobbying presence in Washington, D.C., was New York, she says. Opened in 1941, the office’s primary goal was advocating for private contracts for World War II. Connecticut followed soon thereafter, but state offices in Washington during this time were uncommon.

In fact, she says the explosion of governors lobbying groups really began in the 1960s. The urban renewal trend of the 1960s shifted federal funding from states to large cities. This was viewed by governors with some alarm, and the National Governors Association established a Washington lobbying office in response. The growth of governors associations and individual state offices in Washington continued into the 1970s and ’80s.

Among the reasons that governors open Washington lobbying offices is to place state issues on the congressional agenda that might not otherwise be included, such as earmarks—congressional spending directives to fund special projects. The lobbying offices might be needed due to opposing agendas by the governor’s office and that state’s congressional delegation. State senators and representatives may be less focused on supporting operations of the state than the governor would hope.

Jensen’s book addresses the question of interest group variation: Why, given the fairly clear material benefit a state draws from having a lobbying office in Washington, doesn’t every state have one? Governors’ lobbying offices, she says, enjoyed more robust staffing in the 1980s and 90s but are shrinking and being staffed by younger, less costly employees or contractors.

“We tend to think first of the financial costs and benefits of lobbying offices, but there are also political costs and benefits to consider,” says Jensen. “Governors are vulnerable to the political fallout from the existence of these offices—especially during election season. Opponents often frame a D.C. lobbying office quite negatively, using it to instill doubts about a sitting governor’s trust in the state’s congressional delegation, as proof of a governor’s national ambitions or as an example of excessive spending.”

In fact, Jensen says there have been instances when a governor has closed a Washington lobbying office to fulfill a campaign pledge, only to reopen it later after missing the benefits it brought.

A state might also choose to forgo a lobbying presence in Washington for ideological reasons or because of broader issues pertaining to a state’s political culture.

“Idaho and Wyoming are examples of states with constituents who are more sensitive to the idea of federal government interference in state affairs,” says Jensen. “Or a particular governor might be ideologically against having a representative in Washington. It’s a bit ironic that having a state office—which is there to protect a state’s interests in Washington—can make a governor seem as if he or she is cuddling up to the feds.”

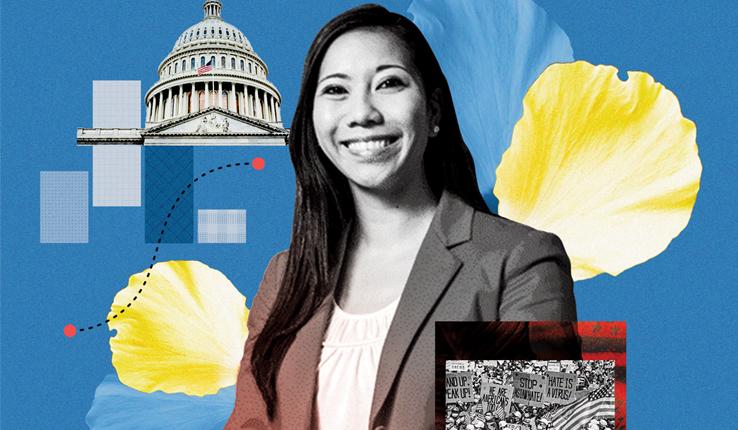

Political differences with Washington leadership may also factor into the decision. For example, in a state like Alabama, where Governor Robert Bentley famously eschewed federal funding for the expansion of Medicaid in protest of the Affordable Care Act, a Washington lobbying office may not play very well back home.

Jensen acknowledges that measuring impact is one of the greatest challenges in the field of interest group research, but says, “if D.C. lobbying offices are doing what they should be doing, they are worth having—somewhat for their ability to lobby on federal regulations, and mostly for earmarks and other funding. Just because there are fewer earmarks today than there used to be doesn’t mean that these offices aren’t helping the states with their bottom lines.”

Story by Lori Friedman

Posted on: