Q&A: How Recent Wage Laws Could Impact Tipped Workers

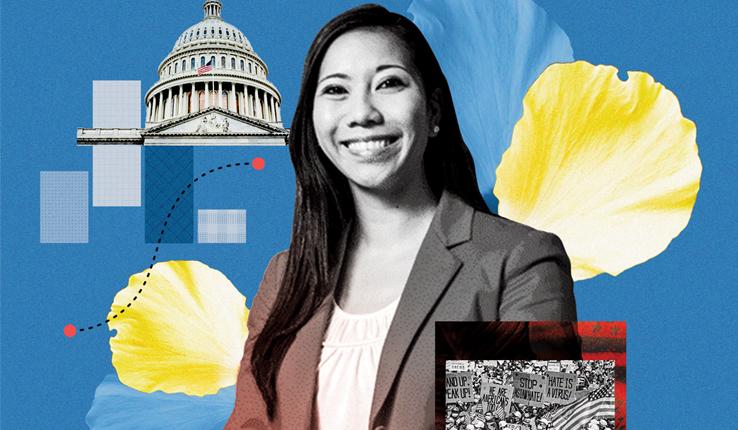

For her book, Holona Ochs, associate professor of political science, interviewed 425 people in more than 50 occupational categories about their experiences as tipped workers.

In December of 2017, the Department of Labor proposed a rollback of an Obama-era federal wage law banning “tip-pooling,” which forces workers to share tips with non-tipped employees and business owners.

A compromise reached by the government's top labor official and a Senate Democrat stopped this rollback before it happened. The deal added a provision to the U.S. Congress' $1.3 trillion spending bill—signed into law by President Donald Trump last month—explicitly forbidding restaurants and other employers from pocketing employees' tips. However, the provision does allow employers, in some circumstances, to share tips with dishwashers, cooks and other back-of-the-house employees who have traditionally been underpaid compared with their counterparts in the dining room.

For her book, Gratuity: A Contextual Understanding of Tipping Norms from the Perspective of Tipped Employees, Holona Ochs, along with her co-author Richard Seltzer, interviewed 425 people in more than 50 occupational categories about their experiences as tipped workers. Ochs, an associate professor of political science, shares her perspective about the potential impacts of recent wage law proposals on tipped workers.

1. Can you tell us what you learned about the experiences of tipped workers while researching the book?

Trust is a central feature of the work environment. Leadership and management play a huge role in either mitigating or contributing to emotional labor costs for tipped employees. Tipping rituals are race-gendered and not equalizing mechanisms. Race and gender are central factors in the experiences of tipped employees. Women and people of color regularly receive lower tips and are often treated with less "respect" and more hostility.

Social class is another factor that regulates the tipping ritual. People who are seen as occupying lower social status positions in society receive lower tips. For example, a young person working in the service industry through college receives generally higher tips than a middle age woman working at a diner.

2. If employers were permitted to keep workers’ tips, how could that impact tipped employees?

"Trust" and "honesty" were consistently mentioned by interviewees. A sense of trust, other regarding behavior—such as opening a door for someone carrying a heavy item—and the belief that "it all evens out" are mechanisms that people who work for tips rely on to deal with the uncertainty and risk in work environments in which their livelihoods depend largely on strangers with only limited situational information about them. A rollback of the 2011 regulation governing tipping would have undermined those mechanisms. This would have increased the uncertainty and risks of service work and increased the emotional costs of their labor.

People working for tips would likely have seen a reduction in their total compensation. People working for tips would also likely be less satisfied with their work. Many of the people we interviewed liked their work because it gave them a sense of control, that they can make more by working harder. This proposal threatened to undermine their sense of agency.

3. What do you mean by “emotional costs”?

Research on organizational behavior operationalizes emotional labor as satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, stress and mood. Research in psychology conceptualizes emotional labor as "holding someone in mind" or "thinking of the needs of others." The work context, work content and the emotional state of the individual interact and affect how taxing the job is on the psychological well-being of the individual.

The most straightforward way to understand emotional labor is that it is the way we feel about our work, the extent to which we feel our work is valued and the amount of energy it takes to "think of the needs of others”—which also means suppressing our own needs sometimes.

4. How could customers have been impacted by a law allowing employers to keep workers’ tips?

Americans tip at an exceedingly high rate. Over 90% of Americans tip service industry workers. This suggests a strong attachment to the ritual, so it is likely that the ritual will persist. However, people will eventually become resentful if they believe that employers, owners or others are profiting from the tips and not the worker.

5. What do you think people should know about the people who serve them for tips?

People who work for tips are more vulnerable to harassment and sometimes feel they are expected to tolerate it. People who work for tips experience the tip as a measure of how much customers value them, not necessarily just how much their work is valued but how much they are valued as people. The tip amount and the process of actually giving the tip—for example, in a very showy manner, highly transactional fashion, or subtly—can reinforce social status in a manner that can reward a person or insult them.

People who work for tips encounter a lot of different kinds of people and often have a lot of intuitive knowledge about how to manage conflict and strong emotional intelligence.

Posted on: