David Brooks has spent a lifetime as a journalist, from the police beat in Chicago to the op-ed pages of The New York Times and national TV news programs such as PBS NewsHour. But in a lecture Tuesday in Iacocca Hall on the Mountaintop Campus, his vocabulary was heavy on seemingly "touchy-feely" words such as kindness, respect, consideration, humanity, morality.

To Brooks, being a good and thoughtful person and making connections with others is imperative in order to combat the state of division in the country.

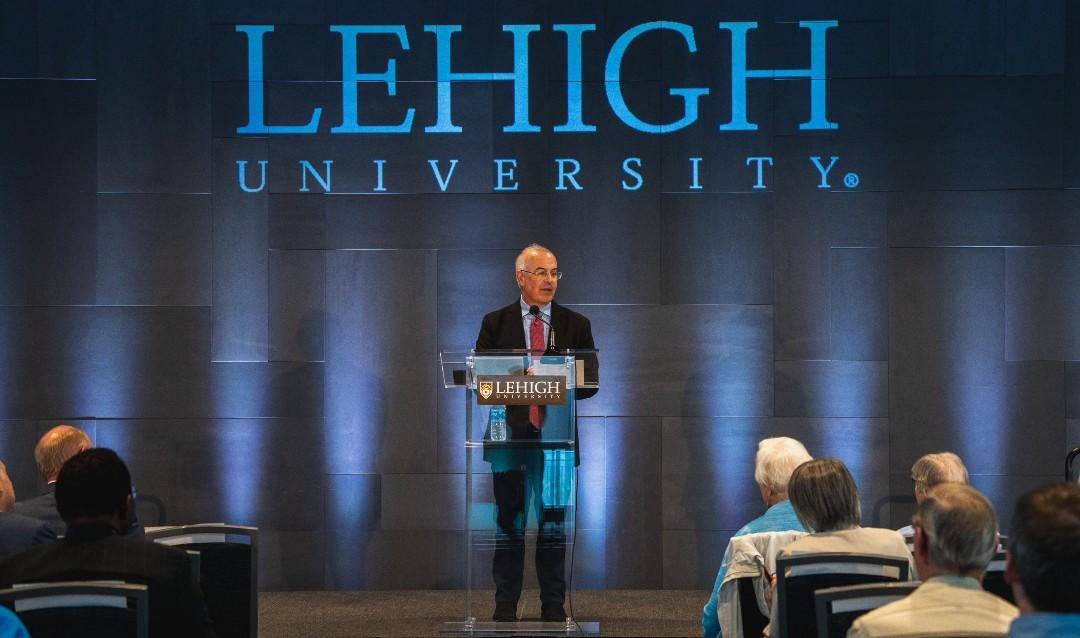

So it's not surprising that Brooks was tapped to deliver the 2024 Hagerman lecture hosted by Lehigh’s Center for Ethics. In his introduction, Michael Gusmano, center director, said Brooks was the perfect speaker, with his combination of “honor, insight and quiet passion.”

Brooks began his visit with a Q&A with Lehigh students and ended with a signing of his newest book, “How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen.”

With his signature low-key and earnest style of wisdom and wit, Brooks held the full house rapt for an hour. He provided a lesson plan for civility and quoted heavily from big thinkers in education, religion, philosophy and science, including Einstein, Tolstoy and Martin Luther King. He told some of the stories of kindness detailed in his book. Some were realized as part of his organization Weave: The Social Fabric Project at the Aspen Institute, whose mission is “to promote the building of connection and weave a rich social fabric in schools, workplaces and throughout every part of life.”

“The topic I was given is ‘Character, Ethics and Politics,’ and my main goal tonight is to argue that these three things can go together,” Brooks began, the audience responding with a collective chuckle. “I’m going to talk about how we can be considerate to each other given the complex circumstances of life.”

Brooks explained that he is not the type of person for whom having social grace and being “morally upright” came naturally, given his upbringing in a Jewish family that was not the “warm and huggy” “Fiddler on the Roof” type. “I come from the other kind of Jewish family. The culture in our family was ‘think British, act Yiddish,’ he said.

He said his early years were spent in New York City, where a teacher said, “David doesn’t play with other kids. He just watches them.” He attended high school in the affluent Philadelphia suburbs, then college at the University of Chicago, where he said he had a double major in “history and celibacy.” He gained mainstream recognition when he was hired as a conservative columnist at The New York Times.