It was at the end of February, when Italy became a COVID-19 hot spot that Charles Stevens first realized the novel coronavirus was going to deal a major long-term blow to the business world.

“Business has faced other pandemics in the past decade or so—SARS, Ebola, H1N1—but they’ve all tended to be fairly localized,” says Stevens, an associate professor of management at Lehigh. “They could make temporary adjustments, compensate for a temporary downturn in one part of the world, but otherwise carry on with only relatively minor course corrections.”

This was different.

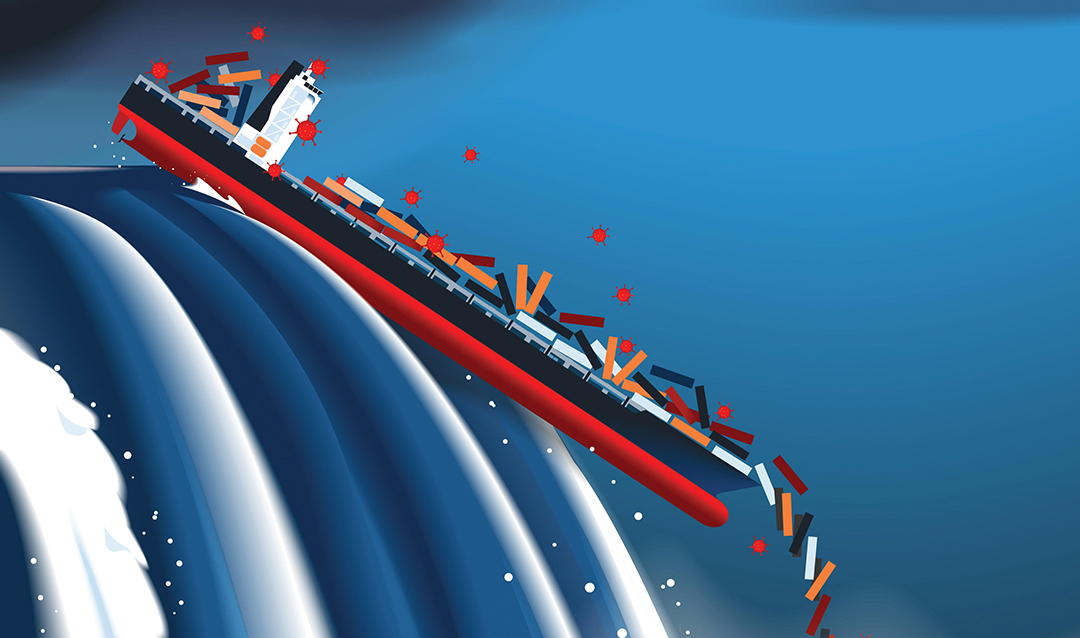

“It’s like a pilot of a plane who sees a thunderstorm ahead—no big deal, just fly around it,” Stevens says. “Until the pilot realizes that there are thunderstorms everywhere and no way around and has to figure out the best and safest and hopefully fastest way through.”

In less than a year, the pandemic has ravaged families and communities around the globe, wrecked economies and cost the jobs of millions of Americans.

As everyone continues to navigate a volatile time, questions abound. How will the pandemic affect businesses, their employees and supply chains in the foreseeable future? Will employers curtail travel? Will white-collar workers continue to work from home? Such uncertainties are complicated by the efforts of American companies to thread the needle of U.S.-China relations in light of the pandemic, the trade war and China’s crackdown on Hong Kong.

Ahmed Rahman saw signs that business supply chains would be seriously altered when Wuhan, China—the major industrial trading hub where the virus originated—was locked down on Jan. 23.

“Seeing the drone pictures survey a completely deserted Wuhan in January augured a troubled future for international business relations,” says Rahman, associate professor of economics at Lehigh.

Images of Wuhan hit home with David Peng, who is originally from China and chairs the new Department of Decision and Technology Analytics (DATA) in Lehigh’s College of Business.

“You could see how bad it was. They were building so many new hospitals because the hospitals and health care providers were completely overwhelmed,” Peng says. “If China is shutting down, it affects the U.S.”

Even before the coronavirus, globalization had already hit pushback from the trade war between the United States and China. The U.S. placed certain tariffs and other trade barriers on the Chinese in 2018 and the Chinese retaliated.

“That was already starting to make it more costly and more difficult to trade goods and services across borders,” says Stevens. “One of the big questions will be: After COVID, what attitudes will people take? Are they anxious and excited to get out and reconnect with the world and travel and look for opportunities around the globe, personally, professionally and otherwise? Or do people retreat back into their shells a little bit and say, ‘Let’s be more cautious about reengaging with the world?’

“It's going to be bumpy going forward,” says Stevens.

Big Data to the Rescue

Fortunately, “big data” can act as a kind of high-tech crystal ball to help countries and companies navigate all the uncertainty.

“This pandemic is going to accelerate the digitization of business,” says Peng, the DATA chair. “With increased digitization, a growing amount of data becomes available to organizations.”

Vast amounts of data are generated from business transactions, smart devices, industrial equipment, cameras and sensors. This data comes in a variety of formats, ranging from structured data such as relational databases to unstructured data in the forms of text documents, emails, videos, audio and images. This data can be used to solve problems and support decision-making in areas ranging from supply chain management to health care, and beyond.

Few companies have revolutionized supply chains more than Walmart, which has invested billions in the technology infrastructure needed to track inventory and forecast demand. While numerous retail giants like JCPenney and Stein Mart have filed for bankruptcy since the pandemic hit, Walmart is going strong, with its online sales in the U.S. jumping 74% in the first quarter of 2020. To meet that demand, data analytics will be even more vital to a nimble supply chain, coping with everything from border closings and state-mandated shutdowns to distressed suppliers.

Real time demand data, along with other data sources not transitionally utilized, such as social media sentiment data, enables retailers to sense the demand much more rapidly and accurately than traditional forecasting techniques, such as time series forecasting, says Peng. “Analyzing large amounts of real time or near real time data also allow companies to have greater visibility into the supply chain,” explains Peng. “This is critical for the supply chain of personal protective equipment in fighting the pandemic.”

“If you find a shortage or disruption, you can respond quickly,” Peng says.

In the fight against coronavirus, researchers are learning more about the symptoms of the disease through information provided by more than 4 million users of an app called the COVID Symptom Tracker. It has helped scientists recognize the effects of the virus on patients with such pre-existing conditions as diabetes and obesity, according to The Scientist Magazine. As a way to speed research efforts, the National Institutes of Health is using analytics from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative database. The Collaborative database allows credentialed researchers to see vast amounts of clinical data culled from electronic medical records of people tested for the novel coronavirus or those who had related symptoms—all while protecting patients’ identities.

Inevitably, information sharing and efforts like COVID contact tracing spark questions about privacy.

“There are examples of countries like China that go through the extreme of mandatory tracing,” Peng says. “That’s effective but it’s not in our value system.”

In searching for a balance between respecting privacy and curbing the pandemic, Google and Apple developed an app for contact tracing that used Bluetooth rather than cellular systems to collect data about whom a COVID-19 patient had been in contact with, but without identifying that patient’s whereabouts. “With the responsible use of technology and big data,” says Peng, “we can carry out contact tracing that successfully balances privacy and public welfare.”

Future with China

Over the summer, Beijing enacted a new national security law, which pro-democracy activists say aims to stamp out opposition in Hong Kong to China’s ruling Communist Party. The law further constricted civil liberties in the former British colony and put more muscle behind squelching political protests.