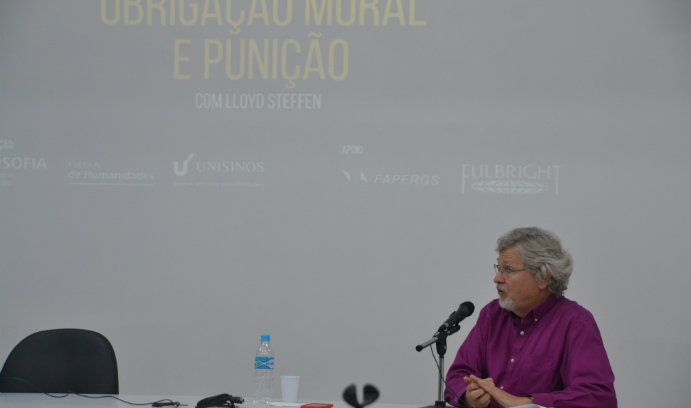

Dr. Lloyd Steffen, University Chaplain and professor of Religion Studies, traveled to Brazil during the fall semester to serve as a Fulbright Specialist. While there, he delivered a week-long seminar grounded in philosophical scholarship entitled Moral Obligation and Punishment at Universidad do Vale do Rio dos Sinos and then repeated the seminar at Universidade Federal de Pelotas.

Professors Evandro Barbosa, Department of Philosophy at the Universidade Federale de Pelotas in Pelotas and Denis Coitinho Silveira, Graduate Program in Philosophy, School of Humanities, Unisinos University in Sao Leopoldo, sought to attract an American professor with roots in philosophy to provide a seminar on the subject of punishment for an audience of graduate students, colleagues and community members. They reached out to the Fulbright Specialist program from the Department of State, which promotes links with scholars from the United States at host institutions overseas.

Steffen was named a Fulbright Specialist in the area of peace and conflict resolution earlier in 2018. Soon after being rostered, Steffen learned of the faculty members' search for an academic with his background to visit their campuses.

Steffen’s work in ethics and religion studies has intersected heavily with criminal justice issues. He proposed a theory of just punishment in his book Ethics and Experience and authored the book Executing Justice: The Moral Meaning of the Death Penalty.

While a public conversation on the subject of the nation’s criminal justice system has reached the highest levels of government in the United States, that’s not the case in Brazil. There are stirrings of activism among former inmates and others who are seeking reform of the harsh conditions in Brazilian prisons, but most Brazilian citizens are not focused on the issue.

“The professors who proposed the seminar see how Brazil punishes those who commit crimes as an important issue. There’s a lot of work to be done getting mass incarceration and criminal justice reform on the national agenda there,” Steffen said. “They wanted to raise intellectually and educationally invigorating discussions around the issue that could spur research and dialogue. That’s where academics can have an impact.”

Steffen said that Brazilian citizens are aware that things are not good in the prisons, but even among those engaged enough to attend his seminar, few had any direct experience. One attorney from the region told him that a local prison built for 1,500 inmates was housing nearly 5,000. Gangs, black markets and violence are common as a result.

“With the lack of resources, inmates without nearby relatives to bring them basic necessities are in a dire situation,” noted Steffen.

Steffen believes the academy has an obligation to do research that will raise issues and start public discussion. “That’s what happened here in the U.S. with criminal justice reform. Criminologists, social theorists, ethicists and others began focusing research on the impact of the war on drugs and mass incarceration on African American communities in particular,” he said. “Authors like Michelle Alexander continued the conversation in the public sphere and now the issue is at the forefront of our national politics.”

Steffen’s direct experience of the American prison system gained through leading Lehigh’s prison tutoring program added experiential connections to the theoretical material he discussed. He said it seemed a similar program would be very difficult to set up in Brazil, yet people wanted to learn more.

During his visit, Steffen also had the opportunity to share his experience as Lehigh’s chaplain with community members. He was invited to speak to a group interested in learning about the role of spirituality in the American university setting.

“When I applied to serve as a Fulbright Specialist, I thought my chaplain work might detract from my scholarship in philosophy, but it turned out to be an asset,” he said.

Since returning, Steffen has stayed in contact with Professors Barbosa and Silveira and hopes to continue to forge deeper friendships. He said the cross-cultural discussions he engaged in may have an impact on his own future research.

“We dove into some very interesting issues about forms of retributive justice where people are held responsible and accountable without ruining their lives,” he said. “Retribution doesn’t necessarily mean an eye for an eye.”

Story by Hillary Kwiatek