Years later, approaching his Lehigh graduation, Willoughby set his sights on California, where his brother was then living. He combed Lehigh’s printed alumni directories to find electrical engineers there and wrote to about 20 of them. “I said, I want to move to California. I’d love to get a job out there, to talk to you,” Willoughby recalls. One Lehigh alum who was working at TRW, now Northrop Grumman, helped him make a connection there, and the rest is history.

Today, Willoughby is paying it forward with the Sarah and Scott Willoughby Scholarship Fund at Lehigh. He also has spoken to Lehigh classes, met with other first-generation students like himself and led students on tours of the Webb telescope while it was under construction.

Do you remember the first time you learned about space? What got you hooked?

It’s an interesting question because a lot of people assume—I’ve been working in space for 32 years—that I grew up and I aspired to that. And the interesting thing was, I really didn’t. I always was a nerd about things, puzzle-solving. I like space. I watched Star Trek. I was always inspired by movies like that, but when I went to [Lehigh] to be an engineer, I wasn’t destined to be in space. I really just liked solving problems. ... My first days of work at TRW, which is now Northrop Grumman, the company I hired into, they put me on a space program. And at that moment in time, I was hooked.

What was it that kept you there and kept you excited about the work you were doing? I probably would have been voted by my friends, most likely not to be in a job for 32 years. I’m impatient or I move around a lot. I like to solve things, but I like trying different things, and to be in the same company for 32 years is pretty amazing. … I’ve actually had well over a dozen different jobs [at TRW and Northrop Grumman], so I didn’t have to leave the team, so to speak. But when I got into space, it seemed like this almost magical thing. The idea that I was building something that would just leave and go thousands of miles away from Earth and have to do its job, wasn’t going to return, no ability to service it, it puts a lot of pressure on you, and, for some reason, I enjoyed responding to that pressure.

Telescopes are sometimes referred to as time machines. Can you explain what that means and what makes the Webb telescope such a powerful time machine?

We love the term because it kind of captures you, right? The time machine. And we are looking back in time. People will look at me quizzically when I say that, and then they’ll ask me if I can look into the future. We can’t do that. But the reason it’s a time machine, and one of the easier references is, our own sun is about 93 million miles away from us, and we look at it, and we see the light. ... Even at the speed of light, that light that left the sun took eight minutes to get to our eyeballs because it still had to travel a distance, 93 million miles. So, in effect, we are looking at the sun as it was eight minutes ago. ... It’s like an archeological dig. When you find the dinosaur bones that have been under that earth because you dig deeper and deeper, you’re finding things as they were historically. Well, we do that with light out there in space.

A significant milestone in Webb’s journey was Jan. 8, when the final major deployment was completed. We saw a lot of clapping and high fives. So was that a different feeling for you than on launch day?

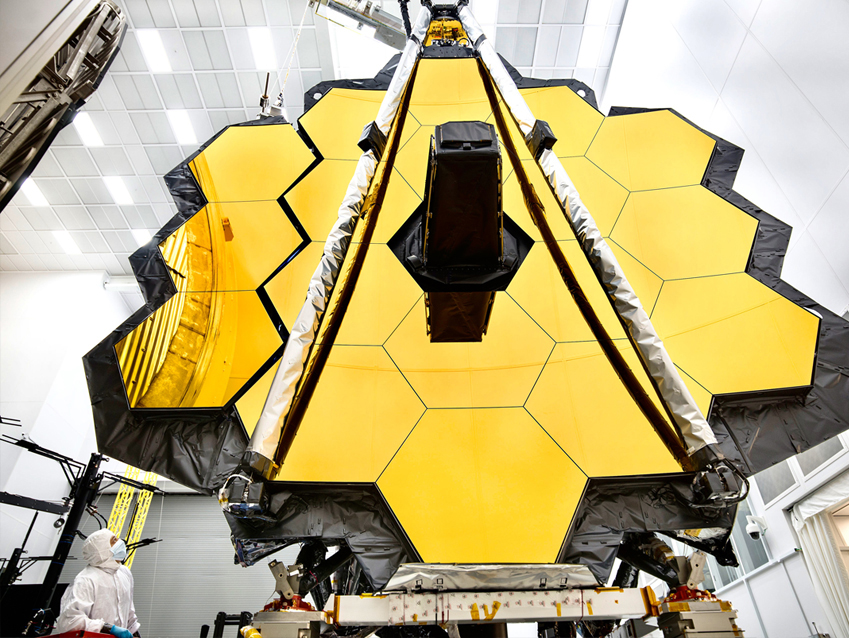

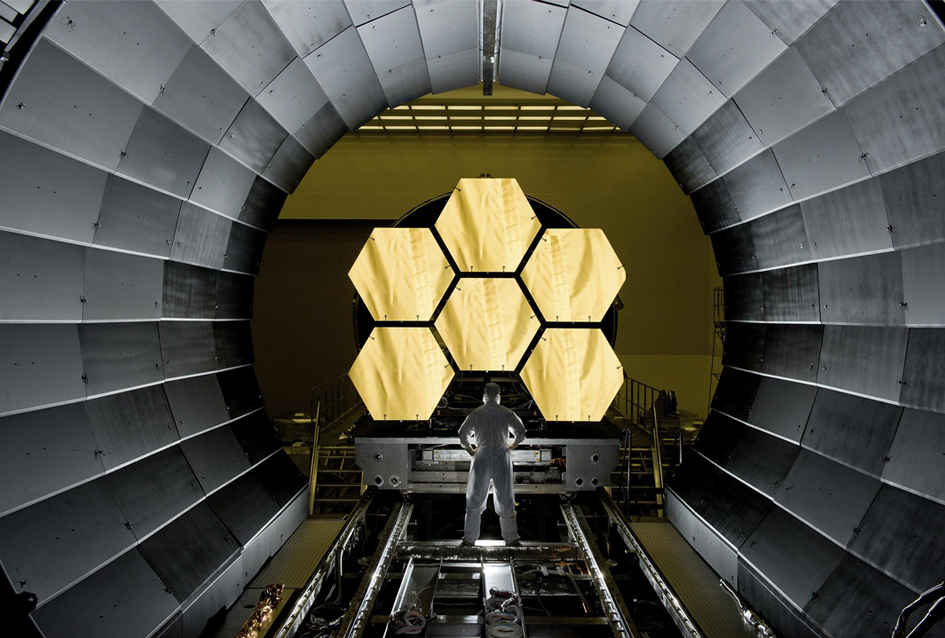

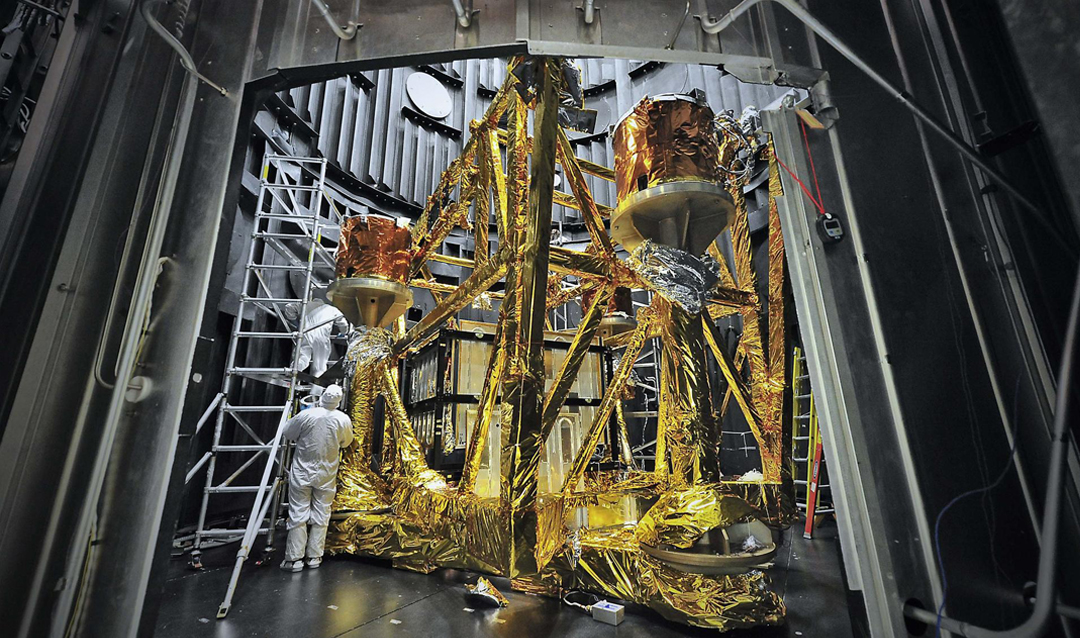

That had a bit more relief in it. I will say that at the rocket launch, it was that emotional feeling of, it’s gone. But it was also, we’ve now got to start the hard job. We need to deploy this in space. Of course, we’ve never done that before. We deployed it three times on the ground, and every one of those, we learn a little more lessons, a little more lessons, as we’re kind of taking the training wheels off, right? This was it. ...

Then for two weeks straight, you’re doing something that has never, ever been done in space before, something with 344 single-point failures, where landing Perseverance on Mars was less than 100, and everybody could tell how intense that engineering feat was. So every day there are mini successes. We fire these nonexplosive actuators, and we see something move—a cover moves, a mid-boom comes out, a structure moves out. That Saturday was the last major deployment. … That elation contained a whole lot of relief. It wasn’t that we were done, but we were done with some of the most complicated things that literally had to go right the first time. ... The most important thing I wanted to do was get into the room where my team was, [the people] who were in the headsets sending those commands, and say, You did it.

You’ve said that working on Webb taught you and your team how to collaborate on an engineering level, and a healthy tension can bring out the best in people. Can you expand on what it takes to be successful?

As engineers there’s a tendency to want to be the smartest person in the room, and it’s good, right? Your whole drive is to get 100 on that test, design something that somebody hasn’t. But what’s most important is to have a bit of humility in that. I always told folks, when you walk into my meetings, you check your ego at the door. You can bring your pride, and I want you to bring all the tools you have. ... But if you can’t hear maybe a different vantage point, then you know it’s hard to put you on this team, because there is no one engineer who can do this.

Willoughby graduated summa cum laude from Lehigh in 1989 with an electrical engineering degree. He went on to receive a master’s in communications systems engineering from the University of Southern California and attended the executive program at the UCLA Anderson School of Management.

Did you come to Lehigh as an engineering major?

I did. I came in as an engineer because I saw engineering as kind of agnostic to status. This was my perception, right? … I applied to engineering because I was good at math and science and I could solve problems. I was the person that if the phone broke, I would fix it. If the refrigerator door was on the wrong side, I would swap it. I could set the clock on the VCR. That used to be a major accomplishment back in my day [laughs].