Best known for her 1982 National Book Award-winning novel The Women of Brewster Place―which was adapted into a beloved TV miniseries that was produced by and starred Oprah Winfrey―Naylor stands among the most influential contemporary American authors. She authored numerous novels illuminating aspects of the experiences of African Americans, particularly African American women, including Linden Hills, Bailey’s Cafe and Mama Day.

There is evidence that Naylor hoped for “Sapphira Wade” to be a capstone of her literary career, report researchers Suzanne M. Edwards, associate professor of English at Lehigh and Trudier Harris, University Distinguished Research Professor of English at The University of Alabama, in an upcoming paper. In the paper, Edwards and Harris write about Naylor’s plans for “Sapphira Wade”―gleaned from the author’s notes, interviews and personal correspondence―and, for the first time, publish excerpts from Naylor’s 131-page manuscript. The paper, titled “Gloria Naylor’s ‘Sapphira Wade’: An Unfinished Manuscript from the Archive,” was just published online and appears in the winter issue of African American Review. The complete manuscript of “Sapphira Wade” is currently being digitized and will be available through the author’s archive in 2020.

“Perhaps the most striking feature of the material in the archive is that Naylor wrote privately about Sapphira Wade across more than twenty years,” said Edwards, who is also director of the Humanities Center and core faculty in women, gender, and sexuality studies at Lehigh.

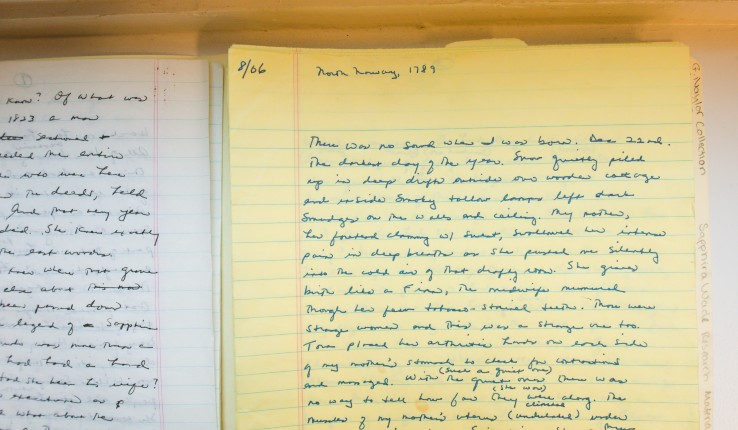

Sapphira Wade is a character in Naylor’s acclaimed 1988 novel Mama Day. She is the great-grandmother of the novel’s title character, Mama Day, the matriarch of the fictional community of Willow Springs, an island off the coasts of Georgia and South Carolina. In the novel, Sapphira’s life is both legendary and mysterious to her ancestors on the island. She is known to have been sold to Bascombe Wade in 1819 and, in some unknown way, to have gained the deed to Willow Springs from him before he died in 1823. It is at that point that the island became an autonomous community of free African Americans during the pre-Civil War era. The manuscript represents the planned novel’s opening chapter and details the early life of Bascombe Wade in Norway, from his birth to his departure for England with plans to travel to India as a Christian missionary.

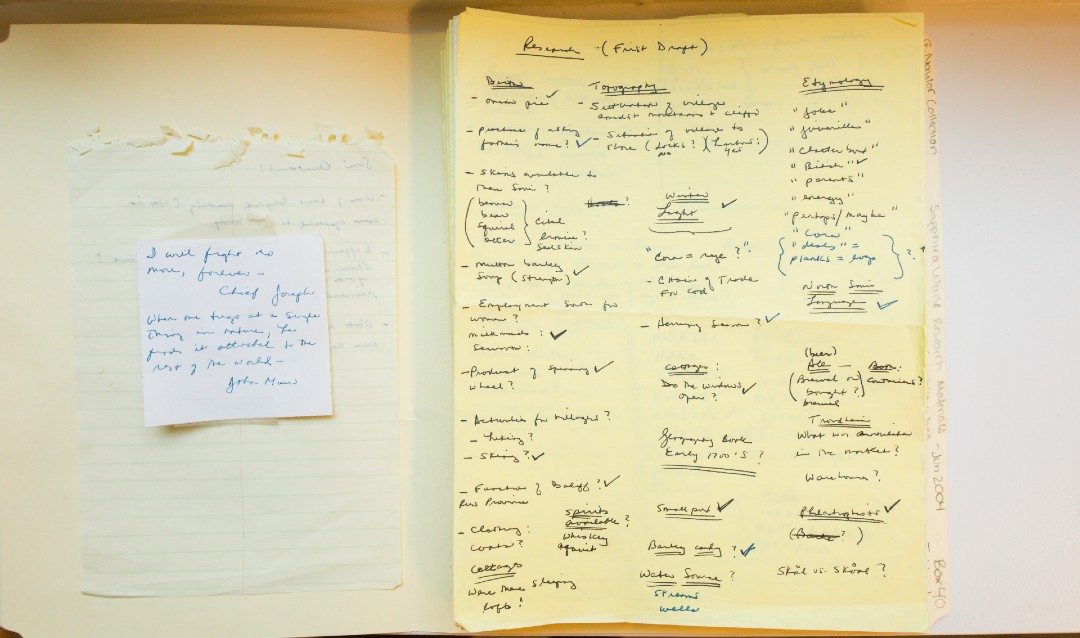

According to Edwards and Harris, Naylor said in a 2000 interview that her intention for the novel “Sapphira Wade” was to tell the story leading up to Sapphira’s acquisition of the land following Wade’s journey from Norway in the 19th century, and Sapphira’s journey from Senegal leading up to their meeting in Savannah, Georgia.

About the unfinished manuscript, the authors write: “How that 35,000-word narrative, dated 2006, may have connected to the events of 1823, when ‘a man named Bascombe Wade sectioned up the island and deeded the entire thing to the black people who were [there] with him,’ remains unknown…”

Though scholars and readers may be disappointed to find that the character Sapphira Wade does not appear in the manuscript’s pages, the authors note: “Naylor’s published interviews as well as the letters, journal entries, and research materials in the archive at Sacred Heart University offer some hints about ‘Sapphira Wade’ beyond Bascombe’s story.”

Still, says Edwards, while what is missing from the manuscript is striking, what the manuscript does contain is also striking.

“The narrative covers almost 20 years of Bascombe Wade's life and fleshes out a character from Mama Day in unexpected ways,” says Edwards. “We are introduced to a man who crosses cultural, linguistic and religious barriers between a Norwegian island settlement and the indigenous, nomadic Sami before journeying to the urban center of Trondheim on his way to missionary work abroad.”

“After completing her book tour for Bailey’s Cafe in 1992,” write the authors, “Naylor turned her attention to ‘Sapphira Wade,’ which she anticipated would be her next novel. In a letter dated June 1, 1993, she speaks to her research agenda: ‘I’m going to Africa in July—Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Gambia to attend a writer’s conference and then to travel a bit with research for my new novel, Sapphira Wade’ (Personal correspondence). Over the years, Naylor took more trips to Africa and Norway as part of her ‘intensive research’ for the novel: ‘I had to physically go to the place in order to walk the terra firma...to breathe the air with this novel’...”

The manuscript, they write, “...stands as a monument to a mysterious, restless genius who traveled halfway around the world to ensure that her conception of a character and his origins was as substantive as history and culture would allow.”

Sapphira Wade Was Naylor’s ‘Muse’

Though the manuscript is dated 2006, Edwards and Harris note that the earliest reference to “Sapphira Wade” among Naylor’s papers is in a journal entry from 1981, when Naylor was a master’s degree student at Yale University. In it, Naylor ruminates about the future, writing: “...After Willie and Lester will come Mom Day and somewhere after her Sapphira. And probably many more in between…”

In a 2006 letter to author Julia Alvarez, Naylor refers to Sapphira as her “muse” and alludes to why she may have put the writing of the novel aside, writing: “I have lived with this story a long time. This woman’s face first came to me when I was working the midnight shift on a hotel switchboard back in the late 70s. I drew it and put it away, knowing that she was my muse. I believe that she has guided me all these years; protected me when I couldn’t protect myself. And I have tried to protect her: that’s why I put away all of my material in 1996 and wrote the Men of Brewster Place…”

Naylor wrote at length about Sapphira in the 2006 letter to Alvarez, write Edwards and Harris: “Describing her sense of obligation to the character, Naylor explains that she could not begin to write Sapphira’s story without first restoring her own ‘sense of self’ after the challenges detailed in 1996: ‘She deserved to have her story told in language that was the best I could find.’ Poetry, Naylor enthuses, has allowed her to begin access to that language…”

Naylor refers to a series of poems she has been crafting that could assist her in accessing that language and concludes, “[F]or now, I’m living one of the lines of my poem”:

A woman must tell stories

To save her life (Letter to Alvarez)”

Though the manuscript and the archives do not answer the question of how the white slave-owner Bascombe Wade―born a “bastard” and fathered by “God”―and the enslaved Sapphira came together and how the land was eventually deeded to her, it does offer biographical details of Bascombe Wade that serve to humanize him for readers.

Edwards and Harris write: “In ‘Sapphira Wade,’ Naylor eschews the Africa-to-North America pathway and invites readers to consider a different kind of potential slaveholder. Certainly, African American narrators occasionally mention English or Irish slaveholders in their narratives, but there is no information about how those foreigners were developed socially and culturally or how they came to enslave human beings. With Bascombe Wade, Naylor makes clear that he is simply a boy and a man, shaped by his illegitimate status (which might influence his nonslaveholding attitude as well), and who exhibits limited interest in politics or the social conditions of Norway beyond what affects his village...As Bascombe embarks on the trip to England, he is essentially a clean political and social slate on which the requirements for practicing slavery would have to be written (if that were possible). At this point, however, he is a likeable, talented young man with whom readers sympathize without qualification.”

The archive does contain some clues about Naylor’s plans to explain how Bascombe Wade and Sapphira meet. Still, the details surrounding Sapphira Wade’s history remain mysterious. Edwards and Harris reveal that the archives contain some written fragments that apply more directly to Sapphira, including these sentences: “Sapphira accepted that she loved this man. The moonlight that coated the wisps of his golden hair. The thin line that ran down the outer edge of the lips that caressed her neck. And she accepted the dagger that lay under her pillow which she could reach back and stiffen his life’s blood with. Sapphira had arrived”

Despite the absence of the completed version, the authors conclude that “... ‘Sapphira Wade’ succeeds in a crucial way. It extends the respect that Gloria Naylor has earned as an artist who was devoted unconditionally to her craft, who produced solid work, and who challenged herself down to the minutiae of that creativity.”

Naylor’s collected papers offer insight into the process of this influential author who wrote in a 1981 journal entry, prophetically given the unfinished work she left behind: “...I will die with a pen in my hand.”