Two cities, two continents, one common concern

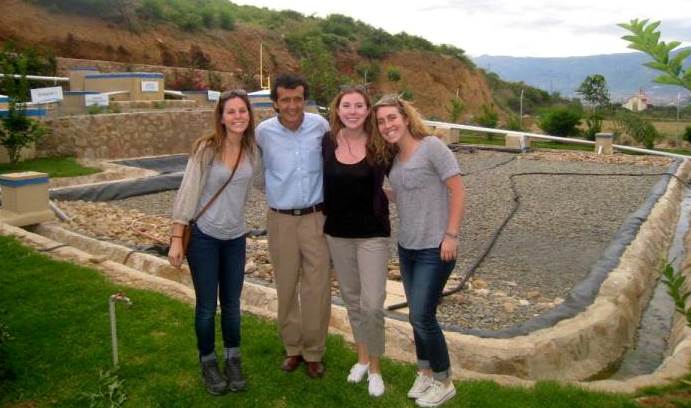

Megan Pulliam, Ellie McGuire and Liz Keenan (l-r) meet with Agua Tuya projects manager Renato Montoya at one of the Quintanilla cooperative’s water collection and purification sites.

Four thousand miles, the western Atlantic Ocean and portions of two continents separate Allentown and the city of Cochabamba in the center of South America. Differences in climate, culture and language also distinguish Pennsylvania’s third-largest city and Bolivia’s fourth-largest.

But the two cities share one important similarity, say four seniors in the Global Citizenship program. The governments of both have, in recent times, triggered public protest when they privatized their municipal water systems.

As their senior capstone project in the Global Citizenship program, Paige McDonald, Elizabeth Keenan, Ellie McGuire and Megan Pulliam are doing a comparative economic analysis of the water-privatization initiatives in Cochabamba and Allentown.

Their study, which included a two-week visit to Cochabamba in January, has been supervised by David Casagrande, associate professor of anthropology, and David Fine, assistant director of Global Citizenship. Funding has come from a Dale S. Strohl ’58 Award for Research Excellence in Humanities and Social Sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences.

In a recent presentation in the STEPS building, the four students compared and contrasted the histories of the two cities’ water-privatization initiatives and the reactions that they touched off. In both cases, the students said, municipal leaders were motivated by financial indebtedness.

In 2000, spurred by Bolivia’s large national debt, municipal leaders of Cochabamba sold the city’s water system, including some land rights, to the Bechtel Corp.

In April 2013, over heated public protest and to help pay its liabilities to the city workers’ pension fund, the Allentown City Council leased the city’s water and sewer system for 50 years to the Lehigh County Authority for $220 million plus royalties.

In Cochabamba, the students said, privatization caused water rates to spike by 400 percent. Residents of the central and northern regions of the city received service, but many in the growing southern sectors did not—a situation that continues today. Opposition groups formed a coalition, rioting broke out and the government reversed its decision.

“The government did not represent the people well,” said McGuire. “It tried to force a top-down solution and it had to back down.”

A view from the ground

In January, the students flew to Cochabamba and set out to investigate the water situation in the shantytowns on the city’s southern fringes, which have mushroomed in the last two decades as rural job-seekers flood into Cochabamba. Their trip was planned by the Foundation for Sustainable Development, which found lodging and hired a translator and a driver for the students.

“Cochabamba is a very cosmopolitan city, like San Francisco,” said Pulliam. “We stayed on the north side of the city with a well-off family. Twenty minutes away, there was no sewer service and there were houses made of tin scraps. It was the largest inequality I’ve ever witnessed.”

The students also encountered contradictions. Bolivia, they note, was one of the first nations in the world to declare water as a human right in its constitution, but while some neighborhoods in South Cochabamba are connected to SEMAPA, the city water system, many are not. A house that Bolivian president Evo Morales keeps on the city’s south side, for example, has service. Houses 500 feet away do not, and must rely on the cooperatives that have sprung up, many with support from Bolivian and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

Not all south-side residents have access to SEMAPA or the coops, however, and many must buy water from delivery trucks at prices that are up to eight times higher than those charged by SEMAPA.

The students spent much of their time with the Quintanilla water cooperative, which collects water running off the surrounding Andes Mountains, purifies it and pipes it to the homes of residents who pay to connect to the distribution system.

Like other cooperatives, the students said, Quintanilla gets advice from Agua Tuya (“Your water”), a consulting agency whose engineers help coops build, operate and upgrade their water systems.

“Agua Tuya is an NGO that gets international funding,” said Pulliam. “Their engineers design water systems for rural as well as urban areas.”

The students toured one of Agua Tuya’s water-purification facilities as well as the Quintanilla coop and a hydroelectric dam under construction near Cochabamba.

Noting that the dam has encountered delays and cost overruns, Keenan said many Bolivians hold the opinion that its purpose is “not to help with the water supply but with the reelection campaign of Morales.” A general election is scheduled for October.

The students said they found the level of civic involvement in water issues to be much more intense in Cochabamba than in Allentown. They attributed some of this to the relative scarcity of water, and the uncertainty surrounding its distribution, in Cochabamba.

“The most interesting thing about this project,” said Pulliam, “has been finding an issue overseas and bringing it back home, and using an anthropological model to study it.”

“It was really valuable for me to be able to apply everything we’ve learned in the Global Citizenship program to this project,” said McDonald. “I’ve proven to myself that I have the capacity to adopt a global perspective. That’s hugely rewarding.”

The Global Citizenship program is open to students in all major fields and in all of Lehigh’s undergraduate colleges. Students are required to take part in at least two overseas experiences. The other countries where McDonald, Keenan, McGuire and Pulliam have taken part in programs include Italy, China (Shanghai) and South Africa.

The students’ presentation in the STEPS building was sponsored by Lehigh’s Sustainable Development program, the Global Union, the Environmental Initiative, the World Affairs Club and the Latino Student Alliance.

Posted on: