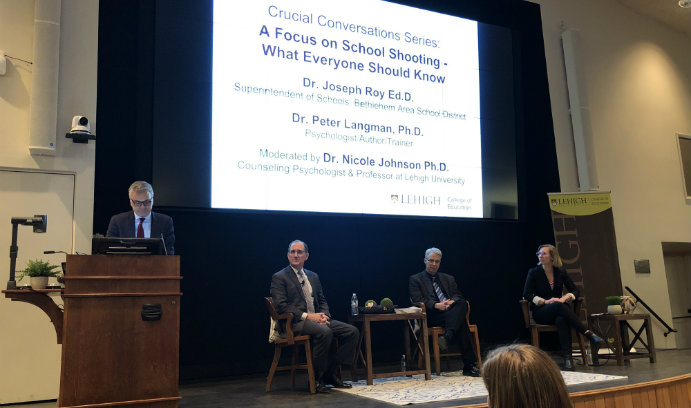

The College of Education hosted a “crucial conversation” with the community Tuesday on a troubling and challenging issue in education—gun violence in schools.

Two Lehigh alumni, Bethlehem Area School Superintendent Joseph Roy ’09 Ph.D. and psychologist and author Peter Langman ’00 Ph.D., offered their expertise in a 90-minute dialog with the program’s moderator and the audience, including teachers and school administrators.

“I truly wish that we did not have to have this conversation tonight about gun violence in schools,” said College of Education Dean William Gaudelli. “I wish that it could be some other focus, something more constructive rather than destructive, an idea that gives us hope rather than filling us with despair.

“But this is what is before us, thrust into prominence by a 24-7 media focus and catastrophes in schools too numerous to bear,” he said. Even one school shooting is one too many, he added.

Questions at the event centered on perceptions and frequency of school shootings, possible warning signs, prevention, and lessons learned, including from the 2018 attack that resulted in the deaths of 17 students and staff at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Florida.

In an exchange with moderator Nicole Johnson, assistant professor of counseling psychology, Roy and Langman offered some hopeful perspectives.

“Overall, schools are the safest places our kids can be,” Langman said. In his talks, he often makes the point that “when it comes to school safety, prepare, but don’t panic.”

Langman said that people’s fears are often magnified and distorted by statistics that can be alarming. Getting accurate data can be complicated, he said, because the definitions of mass school shootings differ among people and groups.

He cited statistics that put the number of school homicides in the country at one-tenth of one percent. “There’s not the epidemic that a lot of people perceive about school shootings,” Langman said. “Some people say, it’s not a matter of ‘if,’ it’s a matter of ‘when.’ No. Most schools will not have school shootings in our lifetime.”

In addition to the perceptions about the depth of the problem, Roy said, people’s perceptions of who commits school shootings can also sometimes run amok. (In the aftermath of the 1999 attack at Columbine High School in Colorado that left 13 people dead, for example, there were concerns about young people who wore trench coats like the shooters did. )

“We don’t want to be putting labels on kids they certainly don’t deserve,” Roy said.

Langman has identified three psychological categories of school shooters—psychopathic, psychotic and traumatized—but he said there is much diversity among those who commit school shootings and no simple answers. Overwhelmingly, however, they are male.

In the aftermath of recent school shootings, Roy said, school safety has become big business. He frequently gets sales pitches for items such as safety glass and metal detectors. But those items, he said, don’t necessarily make schools safer. He said money can be better spent on improving school culture and training staff and teachers on how to better identify attackers.

Langman said that warning signs can sometimes be explicit—students tell friends they are planning an attack, or they write about it or make videos. He said people need to come forward with what they know, and those receiving the information have to take the threats seriously. Often, Langman said, as was seemingly the case in the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School attack, there is a significant breakdown in communication.

“If you see something, say something,” Roy said. He pointed to the state’s new “Safe 2 Say Something” tip line, which has funnelled thousands of tips to a round-the-clock call center in the state attorney general’s office in Harrisburg, as an effort to keep schools safe.

“Schools are a reflection of their communities,” Roy added. As communities across the nation increasingly deal with such issues as mental health and opioid addiction, he said, school officials and teachers are helping students manage those societal challenges. While it’s important to create a healthy place for students in schools, he said, it’s also important to talk about creating healthy communities for students to grow up in.

In response to a question from an audience member, Roy said it would be “completely ridiculous” to arm school employees, such as is proposed in the Tamaqua Area School District, as a way to deal with gun violence in schools. Such a step will create a school culture opposite to what is needed, he said.

Langman pointed to the Police Foundation in Washington, D.C., which has created databases to identify lessons learned from both attacks and averted attacks. The organization lists among its findings: Students should be trained to recognize threats of violence, as well as instances of depression or suicidal signs; parents should be vigilant and monitor their children’s social media accounts, and parents should keep all guns locked and secure.

Langman said everyone in a community has something to contribute in keeping schools safe. In encouraging students to report a safety concern, he said he understands that some young people might express concern about being “a snitch” or getting their friends in trouble.

He said it’s important for parents and school officials to help young people think through those issues so that they can recognize that identifying a potential act of violence is not being a tattle-tell but being a hero, much like the person who identifies a terrorist attack against the country. Also, if students know about a potential attack and don’t report it, he said he points out, that would be “an incredible burden” for them to carry the rest of their lives.