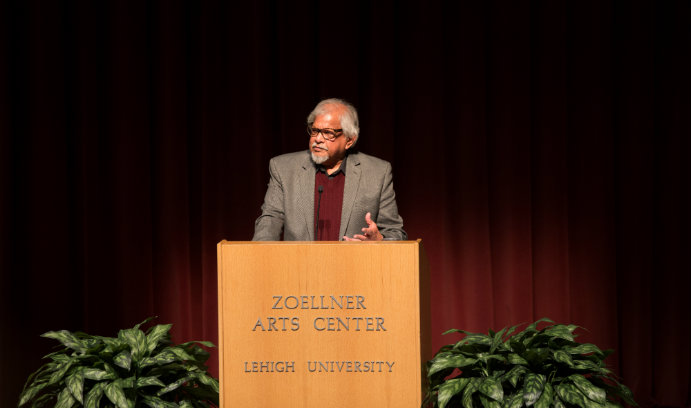

Peace Activist Arun Gandhi Shares With Lehigh His Grandfather’s Lessons

Arun Gandhi, the grandson of Mohandas Gandhi, spoke about nonviolence in a violent world at the 2017 Kenner Lecture on Cultural Understanding and Tolerance. Click here to see more photos from Gandhi’s lecture and his visit to Lehigh.

More than a century ago, Mohandas “Mahatma” Gandhi “found the world to be the same mess that we find ourselves in today: a lot of hate, a lot of prejudice and a lot of violence going on,” his grandson, Arun Gandhi, told a crowd of nearly 1,000 in Baker Hall Tuesday evening. “And that’s why he felt that it was time for the world to find a different way of resolving conflicts.”

Mohandas Gandhi presented his philosophy of nonviolence to the world in 1895. Regrettably, said his grandson, “we have not really learned very much from that philosophy.”

Scholars and practitioners, he said, have examined only the conflict resolution portion of the Gandhian philosophy of nonviolence. “The main part of that philosophy, about how to avoid conflicts, was forgotten altogether. And that’s why whenever we use nonviolence simply as a weapon of choice, it doesn’t always work the way it should.”

Drawing from lessons he learned from his grandfather and stories of their time together, Gandhi offered his thoughts on channeling the energy of anger, the roles of passive and active violence, and the true meaning of peace during his delivery of the 2017 Kenner Lecture on Cultural Understanding and Tolerance.

The Kenner Lecture Series in the College of Arts and Sciences was endowed by Jeffrey L. Kenner ’65. Kenner, who studied industrial engineering and business administration at Lehigh, established the lecture series in 1997. After a career as a management consultant with PricewaterhouseCoopers (then Price Waterhouse & Co.), he became involved in leveraged buyouts and venture capital. In 1986, Kenner formed his own firm, Kenner & Co. Inc. He served as a university trustee from 1995-2002, has long been a member of the university's Asa Packer and Tower Societies, and is a member of Leadership Plaza.

Arun Gandhi is the founder of the M.K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence and the Gandhi Worldwide Education Institute. He has written several books, including Legacy of Love: My Education in the Path of Nonviolence; The Forgotten Woman: The Untold Story of Kasturba: Wife of Mahatma Gandhi (co-authored with his late wife Sunanda); Grandfather Gandhi, a children’s picture book memoir about Mahatma Gandhi’s approach to peace and his influence over his grandson; and Be the Change: A Grandfather Gandhi Story, a companion to Grandfather Gandhi. He speaks worldwide about his grandfather’s lessons about nonviolence.

‘Channel the Energy of Anger Constructively’

Donald Hall, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, introduced Gandhi.

“Dr. Gandhi’s story is a perfect fit for the Kenner Lecture,” said Hall. “Growing up in apartheid South Africa as a person of Indian heritage meant racial confrontation with both blacks and whites. As a young boy, Arun was beaten up by black youths for not being black and by white youths because he was not white. To spare him the fate of growing up in that environment, his parents took him to live with his grandfather, Mahatma Gandhi, in India. It obviously made an impression. ...In a time of conflict, Dr. Gandhi’s message of hope and peace will undoubtedly spark a conversation.”

Gandhi described the anger he felt at being a victim of racial violence in South Africa during his childhood and the transformative power of the two years he spent living with his grandfather. One of the first lessons he learned, he said, was about understanding anger and how to use it “constructively and intelligently.”

“Unfortunately, we are so ashamed of anger that we don’t want to talk about it, we don’t want to teach it, we don’t want to learn about it, we ignore it completely. ... Grandfather said that anger is like electricity—it’s just as powerful and just as useful, but only if we use it intelligently. It can be just as deadly and destructive if we abuse it. So just as we channel electrical energy and bring it into our lives and use it for the good of humanity, we must learn to channel anger in the same way, so that we can use that energy constructively, rather than abuse it.”

At the advice of his grandfather, Gandhi wrote an “anger journal,” in which he recorded each day each time he got angry, not as a reminder of the incident but instead with the intention of finding a solution to the problem. This, he said, helped him learn how to constructively channel his anger.

Controlling that anger, Gandhi said, can have a tremendous impact on the amount of violence we experience. He emphasized the importance of the ability to control one’s mind in order to control anger.

“We think that education and filling the mind with knowledge is all that we need,” he said. “That is just like filling a computer with a lot of software, but if that computer is not capable of handling all that software, it’s going to crash. So our minds absorb all this knowledge, but because we have no control over the mind, we find that at any given moment our mind is wandering in different directions. … It’s only through having a strong mind that we can use the energy of anger constructively and intelligently.”

He described a daily exercise his grandfather taught him, in which he quietly focused on an object that gave him pleasure for a longer and longer period of time each day.

Eventually, he said, “whenever I wanted to focus on any one particular thing, I could focus on that and remove all the distracting thoughts that race throughout my mind.”

Passive and Active Violence

Another story, this one about a pencil, illustrated the depth of Mohandas Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence.

When the young Gandhi threw away the three-inch stub of a pencil, his grandfather explained to him the concepts of passive and active violence. When using natural resources to create an object like a pencil and then throwing it away, explained Gandhi, that waste constitutes violence against nature. Likewise, overconsumption of resources by affluent societies deprives others of those resources, which constitutes violence against humanity. Passive violence, he said, is “the kind of thing that we do every day and that hurts somebody, where we don’t use any physical force and yet it hurts: things like discrimination, oppression, suppression— economic, political, social, cultural, religious—and the hundreds of other things that we do, wasting resources and all these things, which have become so much a part of our life that we don’t even recognize it as violent.”

Mohandas Gandhi taught his grandson that this everyday passive violence fuels the fire of active violence in its victims, who seek justice in a more physical way.

“So logically, if we want to put out that fire of physical violence, we have to cut off the fuel supply. And since the fuel supply comes from each one of us, we have to become the change we wish to see in the world. If we don’t examine ourselves and our attitudes, we will never be able to create peace. Because peace has to be created within ourselves before we can create peace outside,” explained Gandhi.

The Trouble With Tolerance

Gandhi explained how relationships in a nonviolent society are based on respect, understanding, acceptance and appreciation.

“We are interdependent, interconnected and interrelated, and we have to respect that,” he said. “... Each one of us is here for a purpose, and we have to find out what that purpose is. At the very least, our purpose is to make this world a little better by our existence. And when we understand that purpose in life, then we will be able to accept each other as human beings and not identify people by all the labels we have put upon ourselves. Today we have so many labels: gender labels, religious labels, economic labels, national labels, you name it, and we have a label. And every time we put a label on somebody, we are creating a wall between that person and us. And every time we create a wall between people, we are creating potential for conflict. So we have to remove those labels and begin to look at each other as human beings and respect each other as human beings.”

Gandhi also emphasized respect over tolerance.

“We have been talking about tolerance. And tolerance is not what we need between human beings. Tolerance means that I still consider myself to be superior to you, but I’m going to tolerate you because I have to. And that’s not the kind of relationship we want between people. We want a relationship which is based firmly in mutual respect. And it’s only when we are able to do that that we will understand our own humanity.”

The Meaning of Peace

Gandhi closed with a favorite story of his grandfather, about an ancient Indian king who wanted to know the meaning of peace. An old sage gave him a grain of wheat and told him it was the answer. The king eventually learned that by allowing the grain to interact with all the elements rather than hiding it away, it would grow into a field of wheat.

Likewise, Gandhi explained, “if somebody has found peace and they keep it locked up in their hearts, it will perish with them. But if they let it interact with all the elements, it will sprout and grow and very soon we could have a world of peacemakers.

“So I come here today to give you the grain of wheat that I got from my grandfather. And I hope that you won’t let it drop and perish, but let it interact so that all of us together can make this world a better place for future generations.”

Photos by Christa Neu

Posted on: