Nick Dykstra Ventures Forward

From the “Rex” conference room at the Intellectual Ventures corporate offices in Bellevue, Wash., Nick Dykstra ’73 has a spectacular view of the snow-capped Olympic Mountains beyond the downtown Seattle skyline. That Dykstra arrived here, as a senior finance director at the privately held invention capital company, after an extensive and successful career in accounting and finance, surprises even him a bit.

“You go to a business school and are taught a lot about strategy, planning and control, but most of my career steps were results of being improvisational and recognizing unpredicted opportunities that arose,” he says, with a wide grin. “Very few of the things I’ve done could have been planned out far in advance.”

Dykstra, who majored in accounting at Lehigh, went to work for Arthur Andersen in New York City after graduation. Those were some of the darker days in the city’s history, when crime was rampant and the city’s finances were bleak, and he longed to widen his horizons and move to the West. When the opportunity arose, he relocated with the accounting firm to Seattle in 1980.

Once there, Dykstra applied extractive industries expertise gained from client experiences in New York to help advise a U.S. District Court special master appointed to mediate disputes among 12 corporations created as part of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. Signed by President Richard Nixon, the act extinguished aboriginal land claims in exchange for specific regional corporation grants of land and cash. Dykstra spent a lot of time in Alaska over a two-year period as he helped develop policies and procedures to implement the act’s provisions for sharing income from oil, timber and minerals extracted from the granted lands.

In 1983, Dykstra changed paths by becoming chief financial officer of a Seattle venture-financed startup company, Panlabs, which applied emergent technologies of molecular biology to create an extensive collection of analytical tools useful in the discovery and evaluation of new therapeutic and diagnostic products. Just a decade after finishing Lehigh, he was now working in a company that was based on a technology and business model, and using computational tools, that had not existed during his college years.

While Dykstra believes his upper-level courses were critical to landing a job after graduation, he found that most of the specific technical knowledge was soon obsolete. However, he says, the wide distribution of courses that Lehigh required in his first two years had provided social, communication and analytical skills that were adaptable to unexpected and diverse opportunities.

“It was those foundational skills you obtained in the first two years that provided a map for managing whatever came next,” he says.

For Dykstra, what came next was managing a sale of Panlabs to MDS, a Canadian health sciences company. Panlabs formed the basis for the Pharma Services division at MDS, eventually becoming a full-spectrum product development partner for bio/pharma companies, with 3,500 “white coat” employees in labs in North America, Asia and Europe.

“I worked with very interesting people in and outside the company,” Dykstra says, “and I got to travel all over the world.”

In 2007, through some original Panlabs connections, Dykstra joined Confirma Inc. as chief financial officer. The Seattle medical-software company developed and marketed a system for creating 3D color renderings of MRI scans that physicians use for diagnostics and treatment management. In a return to “early stage,” Dykstra and the company’s CEO sat side by side in the center of an open-plan office, “a very West Coast tech experience.”

Confirma was acquired by Merge Healthcare (later a part of IBM Watson) in 2009. At a post-deal lunch with an investor, Dykstra was told he might provide some venture capital experience to Intellectual Ventures (IV), the invention and intellectual property “factory” created by Nathan Myhrvold, the former Microsoft chief technology officer.

“An IV-managed fund was preparing to launch a startup company based on one of its proprietary material science technologies, and I thought a six- or nine-month advisory role there would be a really interesting transition into retirement,” Dykstra says. “But that was eight years ago now; IV is a never-ending source of ‘the next thing’ to learn about and work with.”

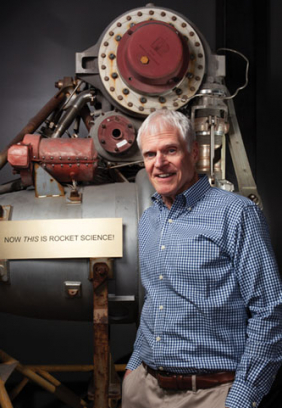

Now Dykstra is enjoying not only his job but his surroundings. Intellectual Ventures’ corporate office reflects founder Myhrvold’s personality and broad interests. Some of the collectibles on display include a life-size T-Rex prop from the movie Jurassic Park and shelves of mechanical calculating equipment, some more than a century old. At the nearby lab, the lobby ceiling is “decorated” with a binary encoding of Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica. Also on display is a working model of Charles Babbage’s 19th-century Difference Engine, a definitely-not-portable mechanical calculator for solving polynomial equations.

With a fulfilling career, Dykstra also serves as a mentor at the University of Washington Foster School of Business. One question he poses to students (as well as job interview candidates) is, would they gravitate toward blackjack or poker tables at a casino?

“The answer is very revealing,” he says, as it provides insight into whether someone likes to play the odds against an indifferent system (like the stock market) or strategize against an active opponent (as with a litigation lawyer). “Having one inclination but being in a job requiring the other,” Dykstra says, “is not a path to happiness.”

Posted on: