A new language for racial inequality

Columbia University author Carl Hart and UCLA psychologist Phillip A. Goff spoke here last week as part of the Martin Luther King Committee lecture series.

Michael Brown, an 18-year-old black man, was unarmed when a white St. Louis County police officer shot and killed him on August 9 in Ferguson, Missouri. The circumstances that led to the shooting are disputed and are the subject of a grand jury investigation. The violence of the protests in the St. Louis suburb that followed the event, and the aggressive nature of the police response to those protests, have become the focus of national attention.

As part of the Justice Department’s response to Brown’s death, Attorney General Eric Holder in September announced the launch of the National Initiative to Promote Community Trust and Justice. Holder named Phillip A. Goff, associate professor of social psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles, as one of the leaders of this initiative, which is designed to build trust between law enforcement and the communities they serve.

Goff, currently a visiting scholar at Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government and co-founder and president for research of the Center for Policing Equity at UCLA, spoke to an enthusiastic crowd at noon Wednesday in the University Center.

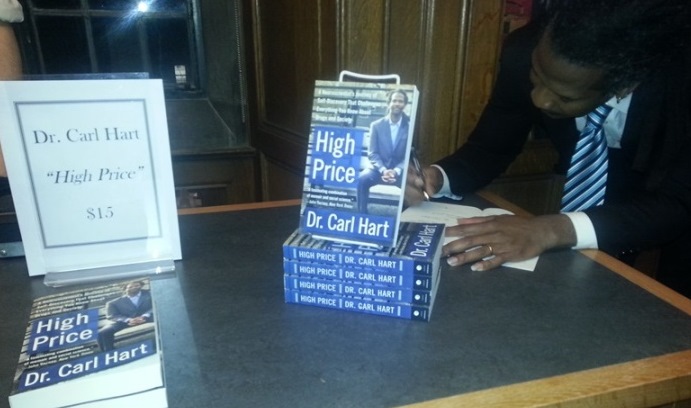

Goff’s lecture, titled “The Science of Preventing the Next Ferguson: Race, Policing and American Democracy,” was one of two addresses given at Lehigh that day as part of the Martin Luther King Committee lecture series. At 4 p.m., in Linderman Library, Carl Hart gave a lecture titled “High Price: Thinking about Drugs with a Social Conscience.”

Hart, an associate professor of psychology at Columbia University, also signed copies of his recent book, High Price: A Neuroscientist’s Journey of Self-Discovery That Challenges Everything You Know about Drugs and Society. The book was the 2014 winner of the PEN/E.O. Wilson Literary Science Writing Award.

Declining prejudice, changing data

Goff, in his lecture, argued that the way people understand discrimination and bias sheds light into how they understand an event like the shooting of Brown.

“How do we make sense of this?” Goff asked. “The way we make sense guides behavior, so changing the sense that we’re making changes the sets of solutions that are available to us.”

Goff examined his foundational research question, which asks what causes discrimination. The notion that bad people cause discrimination, Goff said, doesn’t fit the data because things have changed.

Referring to the Princeton Trilogy, a series of three studies that examined whether traditional social stereotypes had a cultural basis, Goff said prejudice in the United States has declined since 1933. However, increasing rates of infant mortality, unemployment and poverty among the nation’s black population indicate that “the more things change, the more they stay the same.

“How do we understand a world where we have persistent or increasing racial inequality but we have declining prejudice? We don’t have a good developed language for what happens when we have inequality but the inequality cannot be easily traced to racist actors,” Goff said.

Fast and slow traps

The language we need, Goff argued, is that of identity traps.

Goff believes that fast and slow identity traps are the contemporary context of the racial disparities in the U.S. today. A fast trap is an automatic or uncontrolled response such as an implicit bias. Within a fast trap, said Goff, “women become emotional, Latinos become illegal, and blacks become criminal.

“You don’t have to believe [these things] in order to have the associations,” he said. “The reality is, that is the case for the vast majority of those who’ve just been paying attention to their social worlds. You don’t have to be a bad person to think that. But the consequences say things about the character of our society. That’s where the problem is.”

Conversely, a slow trap is self-directed, ruminative and conscious. For example, a self-threat—something a person sees as a threat to a belief he holds about himself—is a slow trap. Goff said masculinity threat, one type of slow trap, could be a contributing factor in the racially disparate use of force by police officers.

Black men, Goff said, are stereotyped as hyper-masculine. And police officers who are assigned to predominantly black neighborhoods, he said, are rewarded for “doing more macho things.” If an officer feels he needs to demonstrate his manhood, he said, racial disparities can result not because that officer is prejudiced towards black people but because he perceives a black man as hyper-masculine. A confrontation between the two creates an “ecology of contested masculinity.

“If you have an identity-based threat in an area, there will be group inequality and it doesn’t matter if the identity-based threat is for the subordinate group or the more powerful group,” said Goff.

“This is not bigotry. This is human psychology. This is a universal feature of being a human being.”

Goff stressed that bigotry does still exist. It should not, however, be the only tool available to understand and solve the problem of inequality.

“We’ve gotten good at using big data to solve little tiny problems, but we haven’t gotten good at using big data to help us live in concert with our values. I think that’s how we start to make sense of this. If this was a problem of character, it would be an easy solve. But we know it’s not an easy solve because even in places where people of good character have tried, they have not been universally successful. So we need a different tool set, and I suggest to you that traps can be a part of that tool set to make it work.”

Focus on “structural causes”

Hart, in his talk, said politicians were misleading the public about the extent of drug abuse.

“There has never been a drug-free society in the history of the world, and there never will be,” he said, “but we pass drug-free legislation.

“The public has constantly been misled to increase budgets for law enforcement, treatment providers and research. Crack has been blamed for high murder rates and for grandmothers having to raise the new generation. Why? In order to avoid dealing with the real problems of poverty, unemployment, substandard education and poor nutrition.”

Hart was also critical of mentoring programs.

“President Obama declared January as National Mentoring Month,” he said. “But mentoring is beguiling. It creates the impression that you are doing something without dealing with the structural causes of societal ills.”

Hart advocated the decriminalization of drug use, the creation of “meaningful employment opportunities,” and an end to what he called the “racial segregation of the workplace.”

Goff and Hart both spoke as part of a Martin Luther King Committee lecture series titled “The Price We Pay: Crack, Cops and the Cost of Bias.”

The event was sponsored by the Africana studies program; the cognitive science program; the Council for Equity and Community; the department of English; the Health, Medicine and Society program; the office of multicultural affairs, the department of psychology; the Social Justice Scholars, the department of sociology and anthropology; the South Side Initiative; and the office of research.

(Kurt Pfitzer also contributed to this article)

Posted on: