Low Birth Weights Tied to Coal Power Plant Emissions

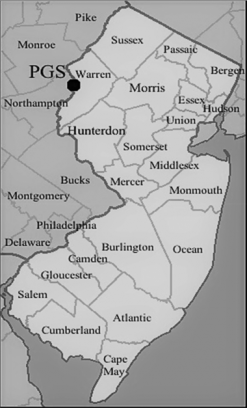

This photo of the Portland Generating Station’s coal-fired power plant in Pennsylvania’s Northampton County was included with the petition filed by NJDEP with the EPA in 2010. Economists from Lehigh and the University of Pennsylvania studied the effects of emissions from the plant on birthweights in nearby New Jersey counties.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has studied the effects of coal-fired power plant emissions on premature mortality, nonfatal heart attacks, hospital visits, acute bronchitis, respiratory symptoms, aggravated asthma, and absence from work and school.

A new study details the effects of the emissions on a previously unexplored area: fetal health.

The study—led by Muzhe Yang, associate professor of economics—is the first to probe the impact on birth weight of prenatal exposure to a uniquely identified large polluter. Drawing on evidence from a Pennsylvania power plant, the researchers studied live singleton births that occurred from 1990 to 2006 in several New Jersey counties that lie downwind of the plant.

They found that infants born to mothers living as far as 20 to 30 miles downwind from the power plant were 6.5 percent more likely to be born with a low birth weight (i.e., less than 2,500 grams) and 17.12 percent more likely to be born with a very low birth weight (i.e., less than 1,500 grams).

The study, titled “The Impact of Prenatal Exposure to Power Plant Emissions on Birth Weight: Evidence from a Pennsylvania Power Plant Located Upwind of New Jersey,” was published in early April in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. It was also featured in an article in The Washington Post titled “Wealth didn’t matter. Pollution from a coal-fired plant, carried miles by wind, still hurt their babies.”

Coauthors include Shin-Yi Chou, professor of economics; Rhea A. Bhatta, data analyst in the department of pathology and laboratory medicine at the University of Pennsylvania; and, Cheng-I Hsieh, associate professor in the department of bioenvironmental systems engineering at National Taiwan University.

“Identifying this causal effect is not only necessary for proposing regulatory policies on plant emissions, but also essential for inferring the long-term health impacts of such policies,” says Yang. “A robust association has been found in the literature between birth weight and outcomes during adulthood, such as health, educational attainment and earnings.”

In the United States, emissions crossing state borders complicate the regulation of power plants. While each state has the statutory authority to regulate plants within its boundaries, regulatory incentives between upwind and downwind states are not necessarily aligned. The results of this study illustrate the impact that transboundary power plant emissions that remain uncontrolled for years can have on public health in the absence of a proper regulatory structure.

The study is based on a unique empirical setting, in which a power plant located on the border between two states has polluted the downwind state for years with its pollution spillovers scientifically proven by the downwind state and also by the federal government.

Specifically, two petitions filed by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) with the EPA against a Pennsylvania power plant—the Portland Generating Station (PGS)—show that sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions from the plant have reached four New Jersey counties as far as 20 to 30 miles away. The EPA eventually ruled that the emissions from the PGS plant alone caused the violations of the SO2 national ambient air quality standards in the downwind state, New Jersey.

According to a 2007 report by the Environmental Integrity Project, the Portland Generating Station was ranked fifth among the 50 “dirtiest” power plants by SO2 emission rate. The first of the two NJDEP petitions, according to the researchers, shows that the 30,465 tons of SO2 emitted by the plant in 2009 was more than double the SO2 emissions from all power-generating facilities in New Jersey combined. The plant stopped burning coal in 2014.

“In addition to identifying the impacts of the emissions from this particular coal-fired power plant on fetal health, the usefulness of this study’s identification strategy is its potential application to other studies examining the impact of upwind states’ power plant emissions, which have been the target of a series of environmental regulations, such as the EPA’s Cross-State Air Pollution Rule,” says Yang.

Story by Lori Friedman

Posted on: