A long memory, a longer road to reconciliation

Meline Toumani’s visit to Lehigh was sponsored by the department of international relations and the Visiting Lecturers’ Committee.

April 24 will be a day of remembrance for Armenian people across the world as they mark the centennial of a genocide that took the lives of countless thousands of their ancestors in a land where Armenians had lived for 2,000 years.

For Meline Toumani, April 24 promises to be another day of mixed emotions, of seeking without finding, of questions without answers.

Toumani wonders if it is possible for ancient adversaries to reconcile when each clings to a different version of history. What is the value of political memory? And what happens to a person who searches for the truth beyond the confines of the clan that has nurtured him?

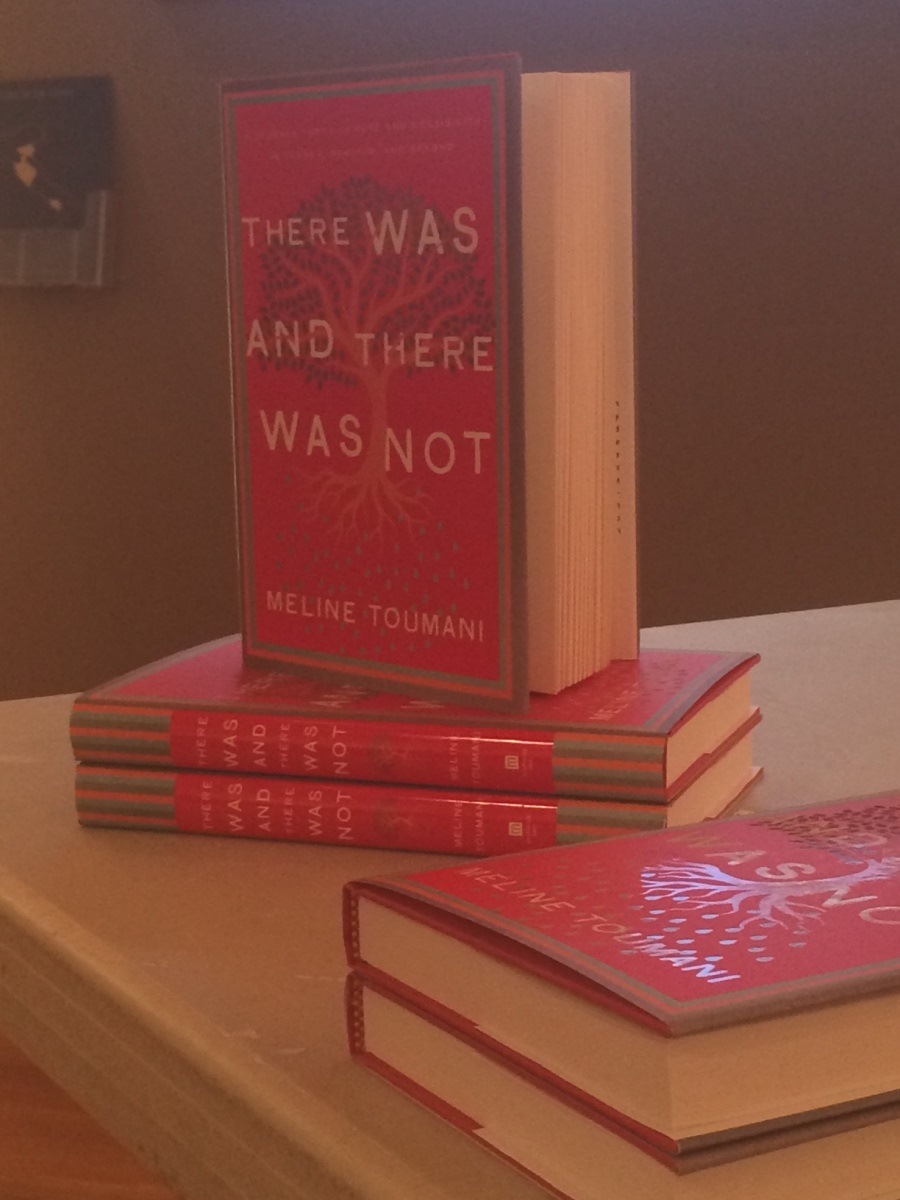

Toumani, an Armenian-American writer, addressed those questions last week when she came to Lehigh to discuss her first book, There Was and There Was Not: A Journey Through Hate and Possibility in Turkey, Armenia and Beyond. Published in November by Metropolitan Books, the book was a finalist for the 2014 National Book Critics Circle Award.

She began her talk by reading from the opening chapter of her book. From 1915 to 1923, she wrote, between 800,000 and 1 million Christian Armenians living in what was then the Ottoman Empire and is now southeastern Turkey “were killed outright or driven to their deaths on the watch of a government that was supposed to protect them. Another million or so survived deportation to the Syrian desert or fled just in time to avoid it.”

Combined with smaller pogroms that occurred in the 1890s and in 1909, the massacres and deportations reduced the Armenian population in that region from 2.5 million to about 200,000 people.

A campaign for recognition

Toumani noted that the Turkish government holds to a different account of the events, asserting that far fewer Armenians were killed by Turks during the Ottoman era, that Turks were killed as well by Armenian gangs, and that the massacres occurred in the context of World War I, when some Armenians supported Russia, which was fighting the Ottoman Empire.

In the century since, Armenians around the world have lobbied for governments to recognize the events of 1915-1923 as genocide. Many nations have granted this recognition but the United States has refrained, out of fear of antagonizing Turkey, which is a member of NATO.

During her childhood, Toumani said, the topic of conversation at Armenian summer camp, at parties and at family gatherings all too often turned to the genocide and the campaign for recognition by the Armenian Diaspora.

“I wondered whether our obsession with genocide recognition was worth its emotional and psychological price,” she wrote in the conclusion to her book’s first chapter. “I wondered whether there was a way to honor a history without being suffocated by it, to belong to a community without conforming to it, a way to remember a genocide without perpetuating the kind of hatred that gave rise to it in the first place.”

A personal burden

The conscious and strenuous act of remembering, she said in her talk, has had another effect.

“It says to every Armenian, no matter what your occupation is, ‘You have a personal burden to fight for recognition.’ I’m not opposed to the recognition of the Armenian Genocide, but for me as a writer, if I’m going to write about Armenian identity, I can’t do that without feeling that whatever I write would be either good or bad for the cause.”

As she wrestled with doubts about the usefulness of her community’s long political memory, Toumani said, she also wondered what motivated Turks to persist in their belief that the genocide had not occurred. A simple question—“Why couldn’t they admit it?”—drove her to move to Turkey in 2005 and learn the Turkish language.

“I wanted to see if I could interact with Turks without being confrontational. I wanted to connect with them personally and not based on what had happened in 1915,” she said. “My intent was to push for a kind of soft, personal reconciliation.”

Toumani stayed in Turkey for two and one-half years but returned home frustrated. She made Turkish friends but few wanted to discuss the genocide. Only one, a sociology professor, asked Toumani how it felt to be in Turkey. The professor acknowledged the personal difficulty for Toumani in making the journey and warned that she was not likely to achieve “soft reconciliation.”

“I realized that if we could not agree on what had happened,” Toumani said of the friends she made in Turkey, “the barrier between us was too great to overcome.”

A place for forgiveness

A dozen people asked questions after Toumani concluded her talk. One audience member asked if the reconciliation Toumani sought would require forgiveness by the victims. Toumani said she had not studied forgiveness and then related the following anecdote.

Not long after she took up residence in Turkey, she said, she met five Armenian Christian women making a pilgrimage to the town of Marash, now Kahramanmaraş in southern Turkey, where several thousand Armenians were massacred in 1920 following the defeat of French military forces by Turkish National Forces during the Turkish War of Independence.

“This was not the first time I had seen Armenians in this part of Turkey,” said Toumani. “But the previous Armenian groups I met had been full of bitterness and anger; they were antagonistic and unpleasant.

“This group of women, who were Protestant Christians, brought the impulse of forgiveness. There was nothing hateful in the way they spoke or behaved in front of their grandparents’ [former] houses.

“This was very moving. It really impressed me to see the spirit and intention of forgiveness and the contrast it presented with much of the Armenian nationalist movement.”

Toumani’s talk was sponsored by the department of international relations and the Visiting Lecturers’ Committee. She was introduced by Arman Grigoryan, assistant professor of international relations.

Noting that Armenia had produced large numbers of chess grandmasters, astrophysicists, writers and composers, and that the country was renowned for its cuisine and its brandy, Grigoryan asked if it was healthy for Armenians in the Diaspora “to make victimhood the national brand.

“You are a courageous human being, Meline,” he said to Toumani. “Thank you for not avoiding the good fight.”

Photos by Lori Friedman

Posted on: