Lehigh Philosophy Conference to Focus on Early Modern Women Philosophers

The Fifth Annual Lehigh University Philosophy Conference will be held Thursday and Friday, Oct. 19-20, in Linderman Library. (Photo by Christa Neu)

If you go to an internet search engine and type “Susanna Newcome, philosopher,” a mere five results appear. One takes you to eBay and one to Amazon, where you can purchase Newcome’s book, An Enquiry into the Evidence of the Christian Religion.

The third result leads to a book about Jonathan Edwards, the 18th-century American theologian and Christian revivalist. On page 100, we learn that Newcome published Enquiry in England in 1728 as “an attempt to demonstrate the reasonableness of Christianity.” We can only know God, Newcome argued, “through observation of things in nature, which exist because of a chain of causation originating with the First Cause.”

Beyond Enquiry, however, the book says that “no details of Newcome’s life have been located.”

The fourth and fifth results of your search are more fruitful; they lead to the Fifth Annual Lehigh University Philosophy Conference. Titled “Women in Early Modern Philosophy,” the conference takes place this Thursday and Friday, Oct. 19-20, in Rooms 200 and 342 of Linderman Library.

Sponsored by Lehigh’s department of philosophy, this year’s conference features presentations in two concurrent sessions by more than 30 scholars from the United States, Canada, England, Romania, Germany, Austria and Lebanon.

The conference, say two of its organizers, will focus on more than a dozen women philosophers, including Newcome, who lived in the 17th and 18th centuries.

“This conference represents a kind of recovery project,” says Patrick Connolly, assistant professor of philosophy. “Some of these philosophers have never been seriously discussed. They have been marginalized or belittled for a long time. But they were serious philosophers in touch with the key issues of their time.”

“These philosophers,” says Roslyn Weiss, the Clara H. Stewardson Professor of Philosophy, “published a significant amount of work but were ignored with no justification.”

The 17th and 18th centuries came on the heels of the Protestant Reformation and were a time of intellectual ferment, says Connolly.

“With the exception of Jewish and Muslim philosophers, philosophy had adhered closely to the traditional Catholic understanding of philosophy. This way of doing things fell apart after the Reformation.”

Advances in science, especially in physics, astronomy and mathematics, also influenced early modern philosophers, says Connolly.

“Isaac Newton, Francis Bacon, Galileo and other scientists obligated philosophers to reconsider their previous conceptions and make sense of a new world view,” he says. “As a result, some philosophers portrayed themselves as starting over. …They were trying to build a system that captured new scientific discoveries.”

Early modern women philosophers corresponded with, and were taken seriously by, their more famous male counterparts, including René Descartes, John Locke and Benedict Spinoza, says Connolly. Men and women alike were concerned with the same issues.

“Women were responding to the same issues that men of the time were writing about. For example, ‘Does God exist?’ and ‘Is the human mind different from the human body?’”

The women philosophers of the time, says Weiss, also wrote on topics that were considered feminine, such as friendship, spirituality and moral psychology, which was a category that included subjects like sentiment, emotions and the passions.

“Men were not writing about these topics,” says Weiss, “and that could be part of the reason that women philosophers were marginalized.”

Women philosophers faced some challenges not encountered by most men, says Connolly. They were less likely to have a formal education or to be educated in other languages, especially Latin, the language in which much philosophy was still being written. Women had limited access to publication and faced financial obstacles, especially if they were not married or were living in a religious convent.

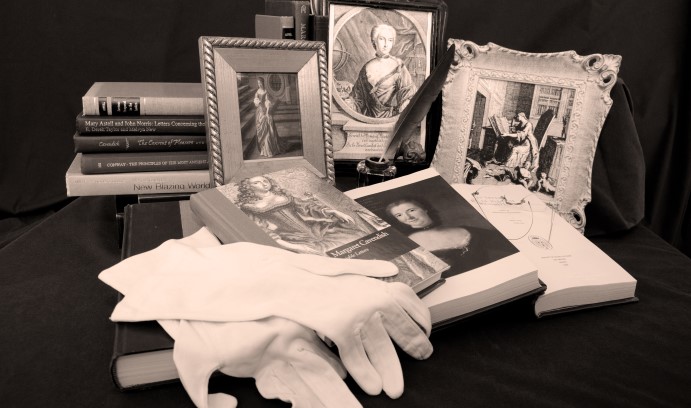

In addition to Newcome, the conference program will include presentations on Mary Astell, Anne Conway, Émilie du Châtelet, Margaret Cavendish, Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, Sor Juana, Mary Wollstonecraft, Catherine Trotter Cockburn, Jacqueline Pascal, Mary Shepherd, Johanna Charlotte Unzer and Marguerite de Navarre.

The topics to be covered include virtue, motion, optics, substance, perception, knowledge, matter, dignity, the mind-body problem, happiness, mereology and friendship.

The conference features two keynote addresses, both in Linderman 200. At 1:30 p.m. on Thursday, Karen Detlefsen, associate professor of philosophy and education at the University of Pennsylvania, will discuss “Émilie Du Châtelet on Methodology in Natural Philosophy.” At 1:30 p.m. on Friday, Marcy P. Lascano, associate professor of philosophy at California State University at Long Beach, will discuss “Cavendish’s System of Nature.”

Faculty members from Lehigh’s department of philosophy and department of religion studies will chair the sessions. Connolly will give a presentation titled “Susanna Newcome’s Cosmological Argument,” which will discuss the proof of God’s existence that Newcome proposed in An Enquiry into the Evidence of the Christian Religion.

“No one has really done anything on Susanna Newcome,” says Connolly. “She was very much interested in the scientific discoveries and the writing of the time, and she referred to Newtonian physics in her writing.”

The annual Lehigh University Philosophy Conference is held every October and funded through an anonymous gift by an alumnus.

The topics of the first four conferences were “The Last Chapter,” “Philosophy Unbound,” “Metaphors in Use,” and “Nineteenth-Century Philosophy.”

Posted on: