How do you want to learn?

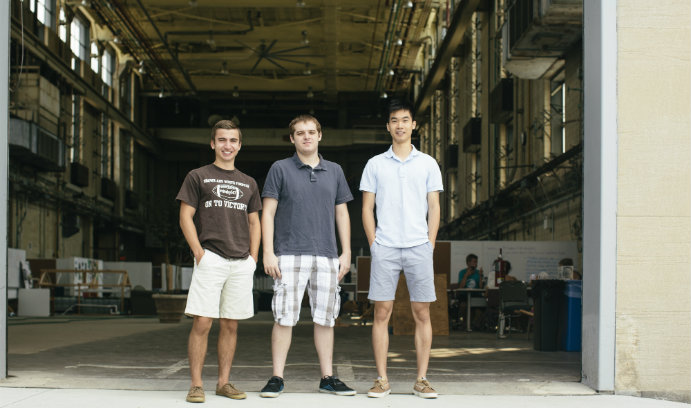

From left, David DiFrancesco, Chris Buglione and Jason Wu of Project Mathete.

When David DiFrancesco ’15 pitched his idea for a Mountaintop project that would explore how students live and learn, he quoted the Chinese thinker and philosopher Confucius, who expressed the belief that people must experience something themselves in order to really understand it.

“I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.”

And so it is with Project Mathete (pronounced MAH-theh-teh), as DiFrancesco and fellow teammates Chris Buglione ’15 and Jason Wu ’15 set out to explore and to demonstrate how students learn best.

Using Mountaintop as backdrop and inspiration, the team has been surveying students and professors about educational issues, asking each other difficult questions, envisioning the classroom of the future and developing a classroom project to test their theories on learning.

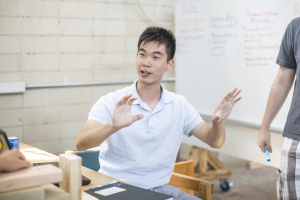

“Our project is based around the idea that there’s some sort of disconnect between the way you learn in class and the way you learn in the real world,” says DiFrancesco. “And we kind of boiled that whole concept down to a few things. First off, we think that the way you learn in the real world is by doing.

“And that’s the way everyone’s learning up here, by doing,” he says, glancing at the Mountaintop space. “So we kind of theorized, everything that everyone learns up here, they’re going to remember for a long, long, long, long time. It’s an experience that’s embedded in them.”

The students also are looking at the effectiveness of technology in the classroom. “Everything we do today, as students at least, is immersed in technology,” he says.

The project gets its name from the Greek word “mathete,” which means “to learn.”

When DiFrancesco was writing the proposal, he settled on the name as a way to spark interest and conversation among fellow students engaged in Mountaintop projects, while also knowing that the Greeks gave the world great teachers in the likes of Plato, Socrates and Aristotle. Besides, he says spiritedly, Project Mathete “sounded pretty awesome.”

The project teams up DiFrancesco, who is studying mechanical engineering in the Integrated Business and Engineering program; Buglione, a computer engineer; and Wu, who is studying mechanical engineering and product design in the Integrated Degree in Engineering, Arts and Sciences program.

The Mountaintop space is a fitting laboratory for the trio. Wu says Mountaintop facilitates learning because students are “exploring their own way out” of problems. “There’s a lot of autonomy….That way you actually learn by doing it yourself and making mistakes and learning from those.”

At the start, the trio surveyed students both at Mountaintop and online to assess the way students believed they were motivated to learn – whether by a thirst for knowledge, by change, by recognition or by a means to an end, like getting good grades and ultimately landing a job.

“Why does anyone learn anything?” asks Buglione. “Why do you go to class? What’s the reasoning behind it?

The top survey answer was “thirst for knowledge.”

However, over concerns whether students’ answers would truly reflect their motivations, and at Buglione’s urging, the team also asked an open-ended question in the initial survey – what inspires you? – then classified the students’ answers. And that’s where the survey results diverged.

“A lot more people are inspired by a means to an end than they would like to actually admit,” Buglione says.

Another survey gauged the effectiveness of technology in the classroom. Many of the students who responded didn’t think technology would help them to learn, while professors felt the use of technology in the classroom would help their students to learn more.

Surprised by the students’ responses, since it conflicted with their theory about the value of technology, the team conducted follow-up interviews. Students who didn’t think technology would help them told them that they had seen it implemented poorly.

“Technology for the sake of technology is a bad thing,” says DiFrancesco, who, like the other team members, felt the survey responses were somewhat skewed because of students’ bad experiences.

With the surveys done, the students now want to assess whether a “doing” activity and technology would facilitate learning, particularly in engineering. They plan to focus on a single course, MECH 102 (Dynamics) and a difficult and confusing concept taught in the course—Coriolis acceleration, the apparent deflection of moving objects when viewed in rotation.

“Can we teach this course better?” asks Buglione. “Or, can we add things to this course to make it better?”

The students will set up four mock classes: one as control group, another with technology added, one with a “doing” activity, and one with both technology and a “doing” activity added. Then, the students will test both comprehension and retention among participants.

And what happens if their theories on learning don’t pan out?

“One of the big things about this project,” says Buglione, “is that even if we don’t find anything, or if all of our preconceptions are wrong, it will still be a worthwhile result because we will have found out that all our preconceptions were wrong.”

Says DiFrancesco, “Everything we’ve done has led us to this point…If it doesn’t matter where you end, there are not mistakes to be made really. It’s just things you can figure out how to do better.”

Photos by Christa Neu

Story by Mary Ellen Alu

Posted on: