If you completed the sentence, “I am ________” 20 times, what would you say? Would you describe your hair color, gender, frame of mind? Where you earned a degree? What sports team you’re a fan of? Your race, health status, role in your family, or a musical instrument you play?

Social psychologists use this “20 statements” technique to gain insight into various components of people’s identities. Most people’s responses can be sorted into categories: individual levels of the self, like stable personality traits or temporary states of being or feeling; relational levels, defined by your relationship to others; and collective levels that describe the self as a member of a category you feel is important to who you are.

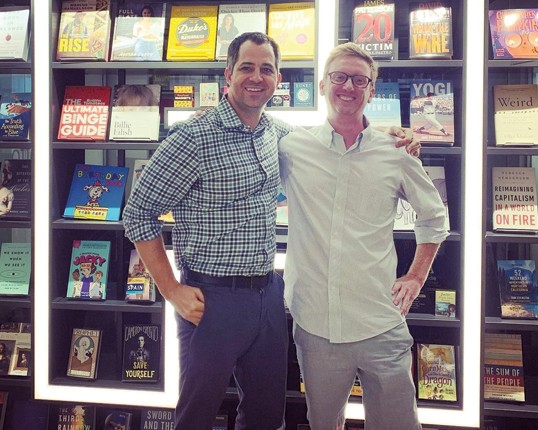

Researchers Dominic Packer, professor of psychology at Lehigh, and Jay Van Bavel, associate professor of psychology and neural science at New York University, are interested in what such answers tell us about social groups, identity, how they impact us and how they transform society.

They explore the topic in a new book, The Power of Us: Harnessing Our Shared Identities to Improve Performance, Increase Cooperation, and Promote Social Harmony, published by Little, Brown Spark.

“As social psychologists, we study how the groups that people belong to become part of their sense of self—and how those identities fundamentally shape how they understand the world, what they feel and believe and how they make decisions,” they write. The book explores how the dynamics of those shared, social identities can divide a world into “us” and “them,” produce conflict and cost lives—as well as foster cooperation, boost organizational performance and promote social harmony.

From Conflict to Cohesion

Packer and Van Bavel started their journey together as students navigating their own distinct identities. They began as office mates and graduate students in the Department of Psychology at University of Toronto: Packer, urbane, fond of wearing suit jackets, who arrived in Toronto by way of Montreal; and Van Bavel, from a small rural town in Alberta, sporting flip-flops and ironic tees, who earned the ire of his office mate by storing a smelly bag of hockey equipment in their shared sub-basement space. In the beginning, the cohesion wasn’t there.

One afternoon, gathered at a catered meet-and-greet with colleagues and influential scholars, Van Bavel choked on a cheese cube appetizer and was unable to breathe. Packer quickly performed the Heimlich maneuver, saving him from choking, as well as from the mortal embarrassment of expiring in front of a room of peers and visiting guests.

The traumatic episode created a different and unique shared identity for the colleagues. They were no longer just office mates who barely tolerated each other—they were a pair of young scientists who’d resolutely survived a near-death experience. The incident set them up to become a scientific team that collaborated on ideas, experiments and data. Their bond strengthened as they both went on to become postdocs at Ohio State University, social psychologists, professors at East Coast colleges, parents and now book authors. All roles that became key parts of their identities.

Their book explores the power within that feeling of “us.” It’s the power of knowing not only who you are, but understanding how that identity is shaped and transformed by the social groups in your world—and how you influence the identities of those around you.

With chapters on individual and shared identities, bias, echo chambers, dissent and leadership, the researchers explore with readers: “What causes people to develop a social identity? What happens to people when they define themselves in terms of group memberships?”

Pandemics and Politics

The COVID-19 pandemic is an example of an event that created shared identities and also revealed conflicting identities.

“The pandemic was a paradoxical event because on one hand, it is a truly global phenomenon, probably more global than anything most people alive have ever experienced,” Packer says. “On the other hand, people’s lived experiences of the pandemic were intensely local.” People experienced the pandemic, from illness to societal disruption, in vastly different ways around the world and within their homes and communities.