Dalai Lama book generates lofty conversations

On Wednesday evening, in a small room on the fifth floor of Packard Lab, over 20 first-year students discussed ideas and thoughts loftier than the rooftops visible from the classroom window.

Among the larger-than-life questions they asked and pondered were: What is a leader?

Is she a simply person in power, or does he compassionately care for and cultivate his followers?

What role should spirituality play in leadership and in daily life?

How should a person combat wrong in the world?

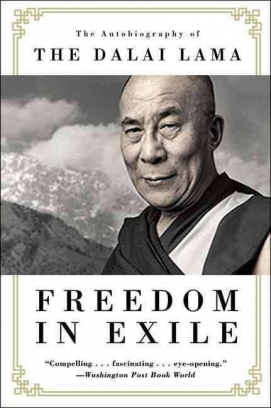

Similar thoughts were discussed all over campus as 50 groups of first-year students met on Tuesday and Wednesday evenings to discuss their summer reading, Freedom in Exile an autobiography of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, as part of their orientation program.

“Lehigh’s Summer Reading Program is such a wonderful opportunity for students to have a common, intellectual experience,” says Lehigh President Alice P. Gast. “To have an opportunity to read Freedom in Exile and to learn His Holiness’ life story, and then to welcome him to Lehigh in July 2008 for a series of teaching and a public lecture, is extraordinary.”

This marks the fifth year of the Summer Reading Program, which was created by Lori Bolden McClaind, Assistant Dean of Student Life, and Kathleen Hutnik, Director of Graduate Student Life. One of the program’s goals is to infuse academic discussion into the daily life of Lehigh students, says Hutnik, who also facilitated two book discussions Wednesday night.

Intellectual life outside the classroom

“I felt that sometimes those great discussions that you imagine having in college rarely happened outside of the classroom,” she says. “That’s such an important and vital part of college life—having the chance to develop an intellectual life outside of the classroom. I think this is one of those programs that helps contribute to that.”

Another facilitator, Brian Slocum, manager of Design Shops in the Design Arts Program, echoes Hutnik’s thoughts. “The most important thing is to get them involved and have open dialogue about the Dalai Lama,” he says.

The faculty and staff facilitators were assisted by orientation leaders, upperclass students responsible for helping first-year students adjust to college life. Dmitry Gurinsky ’09, a chemical engineering major, became an orientation leader because it was an opportunity to “give back to Lehigh,” to develop leadership skills, and to meet other students. He believes that the reading program lets “the freshmen have something in common with each other and for me, as an orientation leader, to connect with them and do different activities that incorporate this book,” he says.

During her orientation leadership training, Michelle Tillotson, ’10 a civil engineering major, was asked to write on a note card everything she knew of the Dalai Lama before reading Freedom in Exile. She wrote “nothing.”

After reading about the autobiography, she discovered that “I learned that I can view him as a political leader and a spiritual leader, but I do not have the same connection with him as a Tibetan Buddist,” Michelle says.

Freedom in Exile describes the Dalai Lama’s life. A series of signs led Tibetan Buddhists to believe that a two-year-old child was the most recent reincarnation of the previous 13 Dalai Lamas of Tibet and an earthly manifestation of Avalokiteshvara or Chenrezig, Bodhisattva of Compassion and the patron saint of Tibet. Bodhisattvas are enlightened beings who have postponed their own nirvana and chosen to take rebirth in order to serve humanity.

In 1950, under threat of invasion from China, the 15-year-old boy was enthroned as the leader of his nation. At 19, he assumed complete political and spiritual rule. In 1959, the People’s Liberation Army of China invaded Tibet, forcing the Dalai Lama and many of his people into exile in India, where he now resides. From Dharamsala India, he has peacefully fought for the freedom of his country and has educated the world about Tibetan Buddhism. His efforts earned him the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize.

Students reading the book were struck by how human the “god-king” seemed. Growing up, Dalai Lama described himself as a willful child, preferring to play rather than study.

Liana Diamond '11 realized that she did not want to repeat the Dalai Lama’s mistake. “He talks about how he wishes he had spent more time studying when he was younger and now he has a reaffirming vigor for knowledge and gaining as much as he can so that he can lead his country. We’re all in college, so we should take the opportunities to further educate ourselves as best as we can,” she said in her group discussion.

Other students were impressed with the Dalai Lama’s attitude toward other religions and backgrounds. They cited his teaching that “all religions aim at making people better human beings,” the Dalai Lama wrote. “I look on religion as medicine. For different complaints, doctors will prescribe different remedies. Therefore, because not everyone’s spiritual ‘illness’ is the same, different spiritual medicines are required.”

The Dalai Lama also wrote about “Universal Responsibility,” which he describes as “the responsibility we all have for each other and for all sentient beings and for all of nature.” In the book, he illustrates this belief through the tenderness he shows to his followers, his aversion to killing animals, and even in his attitude toward the Chinese.

Despite the cruelty of the Chinese, “I took note of the Buddha’s teaching that in one sense a supposed enemy is more valuable than a friend, for an enemy teaches you things, such as forbearance, that a friend generally does not,” the Dalai Lama writes, “if the Chinese oppressed us, it could only strengthen us.”

An inspiring book

Samantha Goldstein '11 hopes to adapt a similar attitude to her daily struggles. “The Dalai Lama was so positive about everything, even though China was taking over Tibet,” she said in her group discussion. “It inspired me to look past the negative things that might be happening this year, the struggles of being a freshman and looking past that and thinking in a broader light.”

To Garland Wong '11, the book had even deeper personal implications. “China was the cause of all this,” he said in his group meeting. “I’m Chinese. When I was reading this book, I felt like I was part of something that was responsible for all this, but at the same time, my grandparents and parents fled China at the same time Mao took power. It’s weird to think of myself as being part of this group that was responsible for all these people dying.”

He then began to wonder how, like the Dalai Lama, he could change history. “What can I do to influence Chinese politics today?” he asked.

President Gast recommends that all faculty, staff, and students take time to learn about Buddhism and the Dalai Lama.

“I encourage our entire campus community to read this book over the coming year,” says Gast, “as well as participate in the many events and opportunities throughout the academic year to explore Tibet, Tibetans and the many facets of their culture.”

Click here to hear quotes from a quartet of Lehigh first-year students taken directly from one of the Dalai Lama book discussion groups.

Becky Straw

Photo by Ryan Hulvat

Posted on: