An Eye for War

John Pettegrew's forthcoming book, Light It Up: The Marine Eye for Battle in the War for Iraq, examines how the U.S. military and aspects of popular visual culture work together to “stylize the eye and create a patterned experience of viewing and seeing war to encourage a large number of young Americans to do what the Pentagon itself believes is antithetical to human nature”—to kill.

"Human beings have this pesky thing called empathy,” says John Pettegrew, associate professor of history. “They have learned and find it valuable to put themselves in the shoes of somebody they don’t know. That is bad for killing, which makes it bad for war."

Pettegrew’s forthcoming book, Light It Up: The Marine Eye for Battle in the War for Iraq, examines how the U.S. military and aspects of popular visual culture work together to “stylize the eye and create a patterned experience of viewing and seeing war to encourage a large number of young Americans to do what the Pentagon itself believes is antithetical to human nature”—to kill.

During World War II, U.S. Army Brigadier General S.L.A. Marshall, an official Army combat historian, interviewed soldiers to determine the non-firing rate among American troops in combat. According to Marshall, up to 85 percent of American troops who had been trained to target the enemy and pull the trigger on their loaded guns did the opposite on the front lines: They either did not fire or aimed and deliberately missed.

“The act of killing is not in close keeping with predominant views of human nature,” says Pettegrew of this apparently innate hesitation. “The Pentagon wanted to overcome that point of hesitation, which it has successfully done since World War II.”

“We [the United States] haven’t fought a war on our own soil since the Civil War,” says Pettegrew. “So my basic research question was: How does the U.S. get a large number of men and women to leave their homes, travel across an ocean, land on foreign soil and, while staying in the line of fire, take the life of a perfect stranger? My answer is [in part] through the eye.”

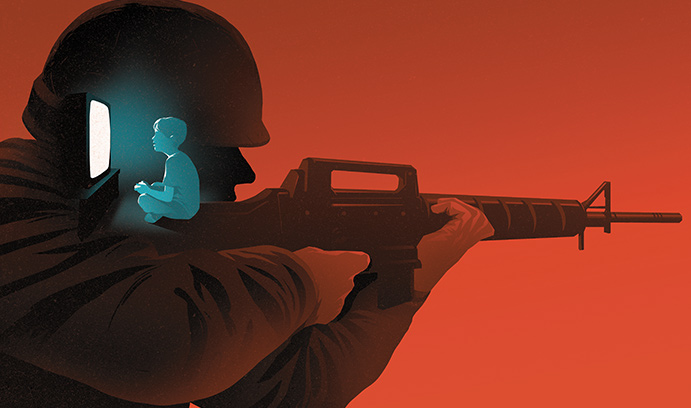

Pettegrew describes two patterns of seeing in combat. The first, he says, is the use of film and video games to create a sense of excitement and challenge in combat, making it seem a close and personal task that requires skill and courage. The second, he says, is to create distance in combat.

Establishing a heroic ideal

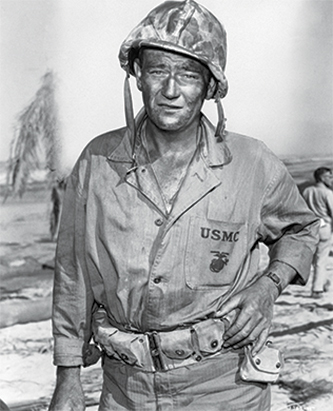

The modern pro-combat vernacular dates back to the post-Civil War era, when short stories, novels and other forms of fiction embraced the theme of martial heroism and the challenge to do in battle what others have done before. World War II brought about the birth of the combat-film genre, with John Wayne the archetype of the hyper-masculine American soldier. These films were “incredibly powerful in reaching into boys’ and young men’s lives at home, at the Saturday matinee, and in school, creating this larger-than-life ideal of the gung-ho warfighter,” says Pettegrew.

Today, he says, the Pentagon works closely with Hollywood in a mutually beneficial relationship that yields authenticity for war films and an opportunity for the Pentagon to communicate its heroic vision of military service.

Clint Eastwood’s recent film, American Sniper, which depicts the life and military service of U.S. Navy SEAL Chris Kyle, exemplifies this relationship.

“There’s no better example of how Hollywood—working with, in this case, the Navy SEALs and the Marines—creates this huge commercial recruitment poster for American military service,” says Pettegrew. “From my perspective, as a historian interested in how systems of violence serve nationalist ends, the primary act of war is not dying for one’s country; it is killing for one’s country. There’s no better example of that core truth than American Sniper. He is made a national hero for his ability—at great removal from his targets—to kill 140-some of the enemy.”

Beyond Hollywood films, Pettegrew also examines an amateur genre that developed during the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. During that time, many American soldiers began bringing handheld and helmet-mounted digital video cameras into battle, filming firefights and later using basic editing software to create videos of the experience. Pettegrew calls these videos “war pornography” because they are meant to reproduce the behavior being enacted on film. The videos, often set to heavy metal music, focus more on weaponry and maneuvers than violence and gore. Their creators first shared the videos via email or on websites developed specifically for regiments. The advent of YouTube in 2005, however, changed everything.

Pettegrew has spent months examining countless examples of these do-it-yourself videos and the thousands of comments posted by viewers.

“For me, as a historian, to be able to go through viewers’ descriptions of what they were feeling while watching war pornography was just invaluable,” says Pettegrew, describing how the comments on YouTube videos were more primary source material than he could ever handle.

“It’s not foolproof evidence, but for cultural history in the realm of the militarization of American society, I couldn’t pass it up. It’s very suggestive of the impact of popular visual culture on the sensibility of young people... As a historian that’s a crucial starting point in understanding how the eye is con-structed for fighting and killing in war,” he says.

Overcoming hesitation

Increasingly realistic, Hollywood-style first-person shooter video games provide an even more immersive experience for civilians and soldiers alike, blurring the line between simulated and actual warfare. Pettegrew says one such game, the Beirut, Lebanon-set Close Combat: First to Fight, is the result of a collaboration between a private commercial video game producer and the Marine Corps, whose goal was to train Marines for urban combat in Middle Eastern cities—a major institutional concern following the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, Somalia, as represented in the book and movie Black Hawk Down.

“The United States has the most powerful military in world history, but if it has to fight in the middle of a crowded urban space, boots on the ground in small teams are the only way to avoid heavy civilian casualties. The U.S. military needs to be able to train these men to work through city blocks, distinguish between civilians and combatants and work as a team to effectively kill the enemy,” says Pettegrew.

Close Combat, used in training for Marines in the lead-up to and early years of the Iraq War, was also released commercially for entertainment purposes. There is little difference between the two versions. As such, says Pettegrew, the commercial version serves as a way to develop among young players a yearning for military experience. It becomes a type of indirect recruiting tool and, for active-duty soldiers, an “important point of continuity between civilian and military life.”

Creating distance

The second pattern of seeing in combat, Pettegrew says, is, in a sense, the exact opposite of the first. The goal is to completely distance the act of killing, to separate the shooter from the target. For instance, drones, initially used for reconnaissance but now also used as weapons, provide this separation.

“Drones have become so central now to United States war making. [They] are the ultimate example of this second strategy of separating the shooter from the target,” says Pettegrew.

Pettegrew describes the ethical and philosophical study of drone warfare and the questions it raises: Is this even war anymore?

“War’s definition basically is that two groups of individuals put themselves into mutual risk. The only sort of ethical support for killing another person is that you are running the same sort of risk of that being done to you. If the person on the other side hasn’t done anything to you, and if you are in no way in danger, what is the ethical support for taking his life? It’s something other than the definition of warfare that the West has understood for centuries.”

A related form of warfare, which Pettegrew calls “fascinating and extremely bothersome,” is the development combat robots. He suggests that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan might be the last major conflicts in which the United States uses predominantly human force.

Pettegrew wrote Light It Up in close connection with the Veterans Empathy Project, an oral history of combat veterans’ experiences in the post-Sept. 11 wars. The project, which Pettegrew directs, aims to bridge the gap of understanding in the United States between civilians who have never served in the military and the many veterans who have by creating a context for understanding the realities of war.

“My next study is on love and peace,” says Pettegrew. “It’s a perfect balance to the past years of studying warfare.”

Illustration by Levente Szabo

Posted on: