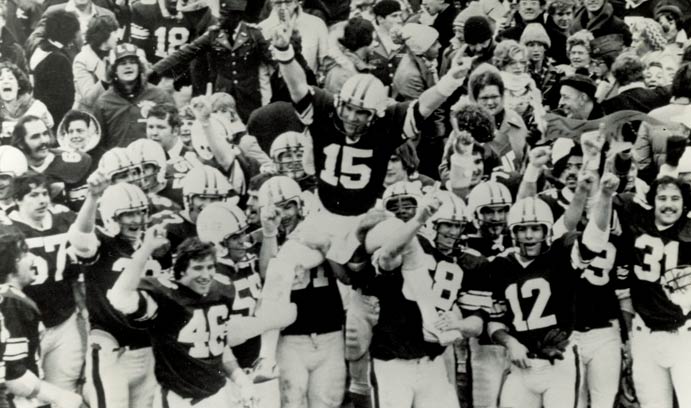

A Team to Remember—And Celebrate

In 1977, the Lehigh Engineers surprised pretty much everyone by winning the national championship. It’s a feat that no other Lehigh team, in any sport, has ever replicated. This fall marked the 40th year anniversary of that momentous game.

The 409-mile bus ride from Bethlehem to Berea, Ohio, was long by any measure. Today, 40 years after the greatest football team in Lehigh history suffered through it, accounts of its duration vary from seven hours to 11.

No matter the true time, there’s no debate about this: The ride back to Bethlehem was even longer.

The Engineers, as they were then called, opened the 1977 season by crushing Connecticut, 49-0. A week later, the team headed west to face Baldwin-Wallace, a Division III opponent. Confidence was high. Despite coming off a disappointing 6-5 campaign in 1976, Lehigh returned a host of experienced players. The team felt it could play with anyone in Division II, and the dominant win over UConn only seemed to confirm that line

of thinking.

“We didn’t have a lot of stars, but we had a tight knit group of guys,” says Greg Clark, a senior defensive end on that 1977 squad. “I don’t know that anyone thought we had a shot at the national championship, but we felt we had a shot at doing something special.”

To outsiders, however, those expectations must have appeared delusional after the Yellowjackets of Baldwin-Wallace (coached by Lee Tressel, the father of former Ohio State coach Jim Tressel) scored two touchdowns in the first five minutes en route to a stunning 28-16 win.

The loss placed Lehigh at a clear crossroads.

Coach John Whitehead was in his second season, and his team hadn’t yet fully adjusted to his no-nonsense style. If he’d smiled once since the Ford Administration, most of his players hadn’t seen it. And certainly not in the wake of that loss in Berea.

“We were reminded out there in Ohio of something maybe we had forgotten,” Whitehead said after the loss. “You can’t just walk out onto the field and expect to win. You need a hundred percent effort—mentally, physically, every other way—to get the job done.”

On the solemn journey home players were riddled with doubts. Was another season destined to slip into mediocrity?

“It was a rude awakening,” recalls linebacker Jim McCormick. “We went in a little bit too cocky and we got whipped. It put things back in perspective. It was a long bus ride home.”

Much longer, it turned out, than the jubilant plane that same team would take back to Pennsylvania from Texas three months later.

The story of Lehigh’s 1977 season actually begins two years earlier.

Led by coach Fred Dunlap, the 1975 squad was a talented one that went 9-2, earning a playoff berth and the Lambert Cup, awarded to the Division II team judged to be the best in the East. Although it lost in the first round of the D-II playoffs to New Hampshire, the outlook for 1976 was bright. Big things were expected from the boys from Bethlehem.

But under first-year head coach Whitehead (Dunlap had departed for Colgate), the Engineers limped to a 6-5 record, which included a loss to hated Lafayette.

“Coach Whitehead was new, and he went through a lot of learning,” says center Rick Adams. “It wasn’t any fun at all. He changed the program around a lot from what we all were used to with Coach Dunlap. There was a lot of resentment. But the spring [of ’77] was a lot different. He had a different attitude, and he ran practice different. That brought a lot more hope.”

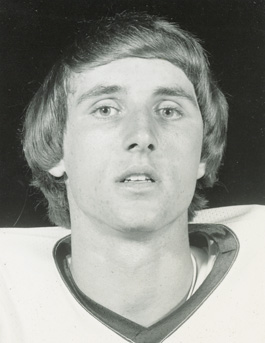

There were a couple other reasons for hope, too: most notably, quarterback Mike Rieker’s arm, and receiver Steve Kreider’s hands. A former signal caller himself, Kreider suffered a back injury and was moved to wideout in 1976. The position shift proved fortuitous for both player and team.

The chemistry between the two was evident from the earliest moments of the ’77 season. Lehigh scored its first points of the year on a 79-yard touchdown pass from Rieker to Kreider; it was the first of 19 scoring connections they would make that year.

“He just had a way of getting open,” Rieker says of his favorite target. “His speed was deceiving, plus no one ever thought that I could throw the ball as far as I could. With Stevie’s speed and my length, he got behind defenders and they just were never used to running 50 yards down the field thinking that they had to keep running. Stevie would just blow by them, and I was given enough time, because we had a tremendous line that was seasoned from the year before. He always seemed to make the catch.”

However strong the bond between thrower and receiver was, on this team, the relationship was not necessarily unique.

To a man, members of the team recount how close they were on and off the field.

“Coach Whitehead always said that he would have to punish us all if something happened up on the Hill, because he knew 10 or 15 of us would be together,” running back Lennie Daniels says.

“To me the most important thing was we had a bunch of guys who banded together,” McCormick says. “Whether it was offense or defense, we all got along, we all enjoyed each other. We appreciated each other not only as football players, but as people.”

With a 1-1 record after the Baldwin-Wallace loss, the team relied on that camaraderie during a difficult week of practice leading up to a game against Penn.

“That was a key turning point,” says Murray H. Goodman Dean of Athletics Joe Sterrett, a graduate assistant coach on the 1977 team. “That game gave us the exposure to what it was going to take.”

With good reason, too. After all, Penn had for years looked at Lehigh as a cupcake—an almost guaranteed win. From 1889 through 1974, the Ivy League school won 34 straight games against the Engineers. But on this day, Lehigh emerged victorious. Kreider caught five passes for 131 yards, including a 73-yard touchdown from Rieker, and scored on a 58-yard punt return.

“From the coaching staff to the players, I think we reacted quite well [to the Baldwin-Wallace loss],” says Walt Whitehead, defensive line coach and John’s son. “There was some very strong leadership all over the place, not just one guy or two guys or anything like that. It was spread all around.”

Victories over Davidson and Rhode Island upped Lehigh’s record to 4-1, but a 20-0 loss to Rutgers slowed the Engineers’ momentum.

“I can remember our seniors coming back into the locker room after that game and in practice the next week, and they were adamant: That’s it, we’re not going to lose anymore,” Sterrett says.

A week later, Lehigh hosted Division I Virginia Military Institute before a Parents’ Day crowd of 13,000. Rieker completed 14 of 24 passes for 229 yards and two touchdowns in a 30-20 win that established the Engineers as a force to be reckoned with in Division II. (Two weeks later, VMI beat the University of Virginia.)

“After that, all of a sudden it was like, ‘Hey, we’re good,’” Adams says.

In a 47-13 rout of Bucknell, Rieker set a school record for most passing yards in a game, with 384. Easy wins over Gettysburg and C.W. Post led into a showdown with archrival Lafayette.

A tight three-point game in the third quarter became a blowout when Rieker threw touchdown passes of 14, 21, and eight yards. The scoring passes gave him a season total of 23, eclipsing former quarterback Sterrett’s school record by one.

“We knew we had to beat Lafayette to have even a chance to get in [the playoffs], because they only took eight teams,” Rieker says. “We had a giant crowd. To do it at home, it was everything that it’s always made up to be. That one had a lot more on the line than any before it or any since, so it was sweet.”

Nine games after losing to a D-III school, Lehigh was named the eighth seed in the eight-team Division II playoff tournament. Its march toward history was about to begin.

A native of Summit Hill, Pennsylvania, John Whitehead graduated from East Stroudsburg State College, and came to Lehigh as offensive line coach in 1967. Even when he got the head job following Dunlap’s departure, he kept his position coaching duties.

“He was an incredibly passionate man, and yet on the surface he didn’t reveal much affection,” Sterrett says. “He maintained a pretty stoic external appearance. If he got loud, it was to chew somebody out or to remind people of what the expectations were. But he was as good as anybody I’ve met in my career in athletics at having intuition about individuals and teams, and what they’d be ready for mentally.”

Players noticed a subtle change in their usually stern coach once the regular season ended.

“Once we beat Lafayette, he let us know that the rest of the season was ours,” Rieker says. “Practices were a little shorter, it wasn’t as rigorous. He wasn’t as demanding during the playoff run. Obviously, he did the right thing.”

Lehigh’s first-round opponent was Massachusetts, and as they did during 11 regular season games, Rieker and Kreider brought their magic to the stadium. The game’s first play saw the two hook up for a 71-yard touchdown, the first of three such connections between them. Lehigh jumped out to a 23-point lead, then held on for a 30-23 win.

It was the school’s first-ever playoff victory.

Next up was a cross-country trip to face the University of California at Davis. Lehigh faced a daunting task: Cal-Davis had won 20 straight home games over four years. Dubbed the Rockne Bowl, the game was televised; one of the announcers was legendary former Notre Dame coach Ara Parseghian. From the outset the game was a shootout, but the quarterbacks actually had little to do with the outcome. Lehigh rushed for 235 yards, while Cal-Davis only managed 25 yards on the ground. The Engineers outlasted UCD, winning 39-30, and with that victory Lehigh was headed to the Pioneer Bowl in Wichita Falls, Texas—home of the Division II national championship game.

“The coaches almost treated things as a reward for a great season,” linebacker Bill Bradley ’78 says. “Not that we didn’t work hard, not that everyone wasn’t serious about it, but there wasn’t this pressure that if you lose this thing you’ve blown it all. We were a very loose group. We were serious and we worked hard, but I don’t remember feeling any kind of tension or pressure. We just wanted to go out there and have fun and play football.”

When the team arrived in the Lone Star State for its matchup against Jacksonville State University, it was met by a surprise: winter.

“All we packed was T-shirts and warm weather gear, because we thought we were in Texas,” McCormick says. “When we woke up and looked across the street and saw the bank thermometer, it was crazy. It was 19 degrees with extremely high winds. We knew it was going to be a defensive-type game.”

All season Lehigh had relied on the potent Rieker-to-Kreider connection to spark its offense, but the gusty winds and frigid temperatures wouldn’t allow for that on championship Saturday. So when the game started, the Engineers threw a wrinkle at their opponent from Alabama: an option offense that the team hadn’t run all year.

The strategy proved to be a brilliant one. Jacksonville State had no answers for a Lehigh offense that racked up 305 rushing yards on its way to a 33-0 shutout, the first ever in Pioneer Bowl history.

“That team demonstrated that they were a complete team,” Sterrett says. “They could win games throwing the ball, they could win games running the ball, and they could also win games with defense.”

Four decades later, the memories still resonate with the members of Lehigh’s first NCAA championship team—perhaps the most searing being the look on Whitehead’s face when the clock showed zeros.

“I was a ball boy in ’61 when he had an undefeated team in Middletown, New York, and I played for him in 1965 when we were undefeated at Carlisle High School,” Walt Whitehead says. “The [Pioneer Bowl] was the most animated and excited I ever saw him.”

“He was not a smiler,” his widow, Bernice Whitehead, says. “But he smiled. That’s all I can say.”

After the game, the team returned to its hotel for a post-game celebration that did not stop for days, and a party that started in Texas and continued all the way back to the Lehigh Valley International Airport, where throngs of fans had gathered to greet the team.

They were champions—the first, and only, football champions Lehigh has ever had.

“My experience with Lehigh and Lehigh football is in its 46th season this year,” Sterrett says. “We’re not the kind of institution that is going to compromise values or academic standards in order to achieve athletic success—we make it harder on ourselves. Not only did the ’77 team win games, but they won it all. That team stands as a reminder to every team that has come after them of what’s possible when you commit yourself fully. It can be done.”

Every five years the team reassembles at a reunion to reminisce about the best football season in Lehigh history. The players may walk a bit slower, their waistlines might have expanded, and their stories may grow a wee bit taller with every telling, but one thing never changes: what they accomplished, together.

“They say right before you die all these scenes flash in front of your eyes, and one of the scenes that I’ll see is standing on the sideline looking toward the scoreboard, seeing my parents,” Adams says. “There’s 33 seconds left to a win in the national championship. At that moment, I knew we were the best in the United States. It was the most incredible high I’ve ever had in my life.”

Forty years later, he hasn’t come down.

Story by Mike Unger

Photos courtesy of Lehigh University Special Collections

Posted on: