A Civil Action

From a Workshop on Syria to a conference on Malcolm X to visiting lecturers such as Madeline Albright and Eugene Robinson, the College of Arts and Sciences' Dialogue Toward Understanding gives students a variety of venues in which to converse critically and constructively about the issues of the day. (Photo by Christa Neu)

Growing up in the Birmingham, Ala., region in the 1960s, Donald E. Hall was witness to what he calls "the real cultural fallout of people who did not understand each other or work toward some sense of mutual social vision and tolerance."

So as he surveys the nation's increasingly polarized and poisonous political landscape, Hall, who became the Herbert and Ann Siegel Dean of Lehigh University's College of Arts and Sciences in 2011, sees the product of a decline in our sense of common purpose and engagement in civil, respectful discourse that stretches back a half century or more.

"This is not new," Hall says. "We are in an era of particularly vitriolic, heated political rhetoric. Part of it's because we're approaching a presidential campaign, but part of it is a real deterioration in terms of the civil discourse that's used through mass media, on television, through blogging, and through the sound bites that are promoted through Twitter, etc. This is a longstanding problem."

And Dialogue Toward Understanding, a signature initiative launched by Hall in 2012, may offer a blueprint for the solution.

The initiative, which includes a series of high-profile public events called Join the Dialogue, reflects not only Hall's personal experiences and research interests in gender and sexuality studies, but one of the core values that has long distinguished Lehigh University, and the College of Arts and Sciences in particular: Instilling in students a deep understanding of how bringing different perspectives across disciplines to bear on a question leads to better answers.

"We are deliberately trying to have conversations that are constructive, respectful and smart," says James Peterson, director of Africana Studies and associate professor of English. "They can get heated. They can be intense. But we as a university community are invested in public discourse that is constructive and critical but not nasty and poisonous.

"We're trying to model for our students how you can have tough, critical, sensitive conversations in a way where you don't have to disparage your discursive opponent. You don't have to talk nasty about them or talk down to them. We can be critical and still be constructive," he adds.

As the college's Join the Dialogue Web page states: "Within the College of Arts and Sciences, our best work is driven by and enhanced through our eager participation in an expansive dialogue that values diverse opinions and differing perspectives, and through which we gain a better understanding of the complexity of social, scientific, and cultural questions, as well as our own blind spots."

Learning to recognize our own blind spots is especially important, Hall says, because holding onto the sanctity of your own worldview leads to "arrogance and dismissal of other people"—traits that are all too evident in today's culture.

"No single one of us holds answers that are so complete that they can't be enriched through the perspectives of others," he says. "What comes from this interchange of different perspectives in a well-functioning civil society is enhanced understanding. We better understand the nature of the problems that we're facing—globally or nationally or regionally. We better understand what divides us and we better understand what unites us."

Challenging Perspectives

A Dialogue Toward Understanding has become central to the College of Arts and Sciences' identity. It is one of the main points Hall talks about with prospective students and their parents.

"We're equipping them to not only be successful in their professional pursuits, but I hope that we're equipping them to be successful as members of a civil society," he says.

The initiative is called a Dialogue Toward Understanding because the College of Arts and Sciences recognizes that attaining complete understanding is a process that has no end.

"But we can make the attempt, and the attempt is what matters," Hall says.

Over the past three years, several large, public events have been held under the Join the Dialogue campaign, which seeks to engage students in conversations that showcase differing viewpoints on major issues. The ideas for the conferences, workshops and lectures "come up organically from what we're already doing," Hall explains

For example, a conference last year marking the 50th anniversary of the assassination of civil rights activist Malcom X was co-chaired by Peterson and Saladin Ambar, an associate professor of political science who authored the critically acclaimed book, Malcolm X at Oxford Union: Racial Politics in a Global Era (Oxford University Press, 2014). The conference attracted an array of internationally renowned scholars, activists and religious leaders to Lehigh's campus for four days to explore the life and legacy of Malcom X.

"What we try to do is tap into the extraordinary expertise of our faculty to make connections to those global conversations and to help draw some of that attention to what we're doing," Peterson says.

Other public events have included a Workshop on Syria in 2013, with a keynote address by Anne C. Richard, Assistant Secretary for Population, Refugees, and Migration at the U.S. Department of State, and a discussion on race and diversity by Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson.

Another key part of the initiative is the Kenner Lecture Series on Cultural Understanding and Tolerance, an endowed lecture series of the College of Arts and Sciences established in 1997 by Jeffrey L. Kenner ‘65. Speakers in the series have included Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, the husband-wife team who co-authored the best-selling books Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide and A Path Appears: Transforming Lives, Creating Opportunity, discussing economic inequality; former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright; National Public Radio host Michele Norris talking about The Race Card Project she started, which asks people around the world to distill their thoughts, experiences, or observations about race into one six-word sentence ; and, this spring, former U.S. Senator and NBA Hall of Famer Bill Bradley.

In addition to the thousands who have attended the Join the Dialogue events, many thousands more have participated through live streaming, with people from as many as 30 to 40 countries around the world joining in.

"I feel that we're contributing to international conversations about social justice, equity, equality, diversity and policy," Peterson says. "And what's beautiful about it is not only are we reaching beyond the room in the actual event itself through media and technology, but these conversations and debates are being extended well beyond the actual events into the university community."

The events are linked back to the classroom through readings and discussions, and those discussions carry over to the residence halls and lunch tables on campus. And each of the events includes opportunities for students to interact directly with high-profile speakers and scholars.

"What we're realizing is that our students have an extraordinary capacity to critically engage," Peterson says. "It's not like these are all lovefests. Students are challenging these speakers, they are asking the tough questions."

Walk the Talk

As director of the Eckardt Scholars Program, a highly selective honors program in the College of Arts and Sciences, Heather Johnson has been in a position for the past five years to recommend students to take part in small group and even one-on-one sessions with high-profile speakers on campus.

"Those moments happen all the time. Most people are unaware of them," says Johnson, who is also an associate professor of sociology. "The opportunity to have these meaningful, one-on-one dialogues is just invaluable. There's no semester-long course that could replace that experience for a student."

As the only faculty member who actually lives on campus, Johnson has a unique perspective on the Dialogue Toward Understanding. She has lived in Sayre Park Village with her husband, Braydon McCormick, twin sons Kyle and Owen, and daughter Meera, since 2012, so she spends a lot of time around students outside of the classroom.

"I see what they're grappling with," Johnson says. "I have this really first-hand look at the way kids live."

Her classroom teaching and research focuses on such admittedly contentious topics as inequality, mobility and immobility in today's society, social class and race, —including how race and class intersect—so Johnson has a lot of experience engaging students in civil and respectful discussions on challenging topics. But for Johnson, modeling that behavior in the classroom isn't enough.

"Doing it in the classroom is really important, and at a residential university like Lehigh, doing it outside the classroom is just as important, if not sometimes even more important. That's why I'm so passionate about living on campus," she says. "Because students need to see that a professor does this not just when they're teaching in front of the class, but when they're living their life."

Living on campus has also led Johnson to believe that the stereotype of students today being unable to communicate because of their constant connection to their cellphones is unfair and inaccurate.

"I don't think it's as negative as people think," she says. "In some ways, they're really connecting. They're actually having dialogue toward understanding, believe it or not, through SnapChat and texting because it allows them to say things to each other they probably wouldn't say face-to-face. I think they're really communicative, it's just not in the way we have been and that we think is ‘right.' I think in some ways, they're actually connecting a lot more than my generation did. And in some ways, they're less cylindered, less siloed, than people think they are."

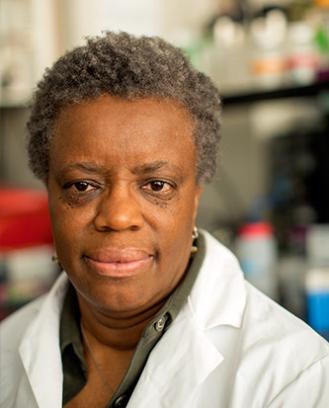

Vassie Ware, professor of molecular biology and co-director of Lehigh's Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) program, also has considerable contact with students outside the classroom as an adviser to the STEM Live Lehigh residential community and the RARE (Rapidly Accelerated Research Experience) program for students majoring in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM), and as a Faculty Fellow at Umoja House, a residential community established to enhance the campus atmosphere for underrepresented students of color at Lehigh.

And what she sees is a place where "young people learn how to address their differences. I don't think it's that they're avoiding the discussion. I think it's that they accept that this is your background, this is how you were shaped. We are now here at Lehigh. This is what we have in common. There's a strong bond in many instances among people as a result of the Lehigh experience."

That represents a "radical difference" from Ware's own first days on campus as a new faculty member in the 1980s. "There was a time when, in all honesty, I didn't think I would stay because it was not an environment that was friendly. Early on, I had some pretty unpleasant experiences with students. Not in the classroom, but on campus and feeling not safe. I don't feel that way anymore."

Ware describes the climate on campus at the time as "somewhat bound. Bound in conversation, limited in conversation. I think there wasn't enough diversity for people who were diverse to feel that comfortable. The environment felt restricted in ways that have clearly changed. If I could say that there was something more dramatic than 180 degrees that would in fact be the case. I've seen that evolution."

And Ware has also seen the difference in campus culture made by Lehigh's HHMI programs, which promote interdisciplinary teamwork.

"You have to be able to anticipate seeing cross-connections and how that's going to change fields and advance knowledge," she says. "I think our students have really benefited from this."

Accepting the Challenge

The College's new sense of mission is clearly making a difference, as it attracts the largest first-year classes ever. It also has caught the eye of two major national funders.

Lehigh's Africana Studies program was recently awarded a prestigious $500,000 challenge grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, an independent federal agency that funds high-quality research, education and public programs at colleges and universities, museums, and other institutions across the United States.

The funds will be used to create an endowment to expand the Africana Studies program at Lehigh, including enhancing curriculum, increasing public humanities initiatives and strengthening the program's community partnerships to further explore public concerns and social justice issues related to race, politics, gender, religion and other areas. The three-to-one matching grant, announced in December 2015, requires Lehigh to raise $1.5 million over the next five years.

Additionally, an $800,000, three-year grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation announced in January 2015 funds the college's efforts to integrate emerging digital media with community engagement. The Mellon grant backs Engaging Undergraduates with the Local Community through the Digital Humanities, an initiative to support faculty and student work telling Bethlehem's story using new digital media. Like other American cities, Bethlehem confronts issues of immigration, education, religion, economic hardship and revitalization, and the Mellon grant supports chronicling the common issues of social justice and a city's evolving history.

"I think there's a real excitement now around our college that comes out of a sense of common purpose and an ability to talk about what a liberal arts education and an education in the College of Arts and Sciences really does for students and for their long-term prospects, whether it's their vocational aspirations or just the way they will be successful citizens," Hall says.

Posted on: