A writer gets his due

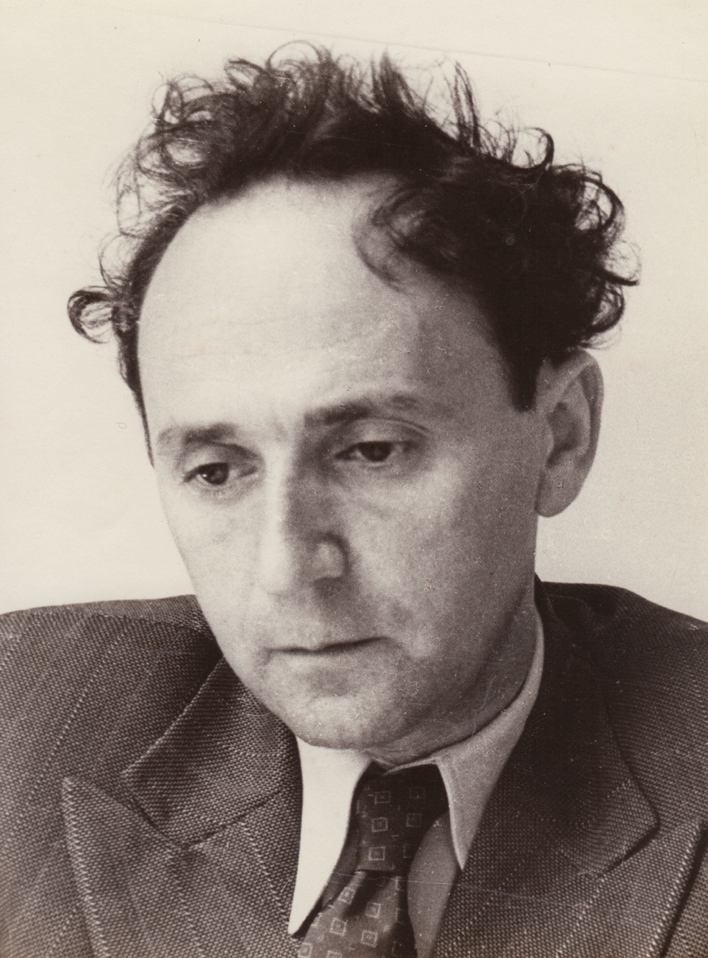

Israel Zarchi, 20th-century author, translator and Polish immigrant to Palestine who advocated a blend of cultural and political Zionism, is the subject of a forthcoming book by history professor Nitzan Lebovic.

The Internet’s search engines are usually more than adequate to the challenge of finding information sources.

Such, however, is not the case with Israel Zarchi, a writer and translator who divided his short life between Poland and Palestine in the first half of the 20th century.

At the top of the Google search results for “Israel Zarchi” is a Wikipedia article about his daughter, Nurit Zarchi, an award-winning Israeli poet and journalist. Zarchi himself merits scant attention. Two sites on the first screen of Google results list the Hebrew titles to some of his works. An author page in Hebrew is virtually empty. The last item on the screen links to a brief discussion about Zarchi in the Romanian translation of A Tale of Love and Darkness by the acclaimed Israeli novelist Amos Oz.

Otherwise there is nothing—no clue that Zarchi wrote six novels and seven collections of stories, no hint that he made a major impact on the literary life of Palestine in the 1930s and 1940s, no suggestion that his insights and observations might still be timely, seven decades after his premature death.

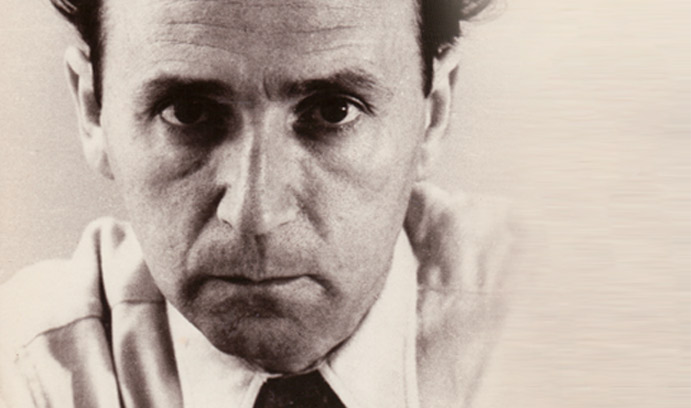

Nitzan Lebovic, assistant professor of history, hopes to give Israel Zarchi his due when his second book, Zionism and Melancholy: The Short Life of Israel Zarchi, is published later this year.

Lebovic, the Helen and Allen Apter ’61 Chair in Holocaust Studies and Ethical Values, was introduced to Zarchi’s works when a professor at the University of Tel Aviv recommended that he read the only one of Zarchi’s novellas that has been reprinted since the 1940s.

“That novella portrays German-Jewish refugees who escape from Germany and arrive to a small hostel in Jerusalem during World War II,” says Lebovic. “They are not able to speak Hebrew and no one around them speaks German. The novel is an amazing piece of literature.

“I was curious—why had this amazing author never been explored or analyzed? Why did no one know his name?”

Three years ago, Lebovic discovered Zarchi’s lost literary archives when the central literary archive in Israel was moved to a new location. Last year, with funding from a Humanities Center grant, he spent the summer examining the archives, which contained letters, diaries and unpublished manuscripts. The work was completed during a pre-tenure leave Lebovic took in 2013-14.

“Reading Israel Zarchi,” says Lebovic, who was born and educated in Israel, “you can gain a window into the life and culture of the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s. The Jewish world of that time was much more varied than we tend to believe. There was an open debate then, all parties participated.

“Certain ideas that seem really radical or even treasonous to us now—Jews and Palestinians living together in the same political structure—were possible, fine, in early 20th-century Palestine.”

A time of tumult and melancholy

Israel Zarchi was born in Poland in 1909 and immigrated in 1929 to what is now Israel and was then the British protectorate of Palestine. Like many Jewish immigrants to Palestine, he made his living doing physical labor—farming and building roads.

The late 1920s and 1930s were trying times for Jews: the Great Depression had started and fascism was ascending in Europe. The countries from which Jews were emigrating were becoming increasingly anti-Semitic. But in Palestine, says Lebovic, the hopes of many Jews would be dashed.

“The early settlers arrived to find a desert. There was no basis to the myth of a land of milk and honey. The immigrants received very little support from Jewish communities around the world. Many became desperate and sad. According to one historian of medicine, 10 to 12 percent of the Jews immigrating to Palestine committed suicide.

“At this time, Palestine had few cities. Jerusalem was poor, Jaffa and Haifa were mostly Arabic, and Tel Aviv was just getting started. There were not many options for the settlers. Either you worked the land or you lost out.”

Many Jews in Palestine, says Lebovic, suffered from melancholy, which he defines in Freudian terms.

“Freud, in a 1917 essay, described melancholy as a pathological version of mourning. Mourning itself is healthy; there are different stages you go through and you can differentiate yourself from what you have lost. Melancholy is the inability to separate the self from the lost object, which can be a person, a past life, something left behind.”

The Zionist demands on the Jewish immigrants to Palestine deepened their sense of melancholy, says Lebovic.

“One core demand of political Zionism was that immigrants leave behind traditional Judaism and stop their involvement with the old Jewish exilic life. Zarchi felt this—he was a Yeshiva student, educated in the traditional Jewish way. He had to secularize, to negate his past, to experience Freud’s definition of melancholy: if you cannot mourn the past and you have to suppress it, this causes a repetition of the pathological inability to separate from the past.

“At the same time, Zarchi made a major contribution to the creation of modern literature in Hebrew.”

The three sub-schools of Zionism

Complicating matters for Jews living in Palestine were the conflicting interpretations of Zionism, and the debates they triggered.

Zionism, says Lebovic, is defined by its adherents as “an ideology of finding the Jewish people a home in the historical territory of Palestine that is identified with the biblical Israel.”

Three “sub-schools” of Zionists existed in Palestine and persist today, says Lebovic. Political Zionism “strives to bring together the Jewish people, after 2,000 years of exile, and give them a national collective identity. The unofficial discourse claimed to make Israel ‘a nation among the nations,’ or to normalize Jewish existence on the basis of national, secular identity. However, that approach—identified with Theodor Herzl and David Ben-Gurion, the fathers of Zionism—has given way to a reactionary interpretation of Zionism.”

The second sub-school, says Lebovic, is a “right-wing revisionist interpretation of Zionism that seeks not just to bring Jews back to Palestine but also to fulfill the theological and prophetic promise of living in the Biblical territory of Israel—thus requiring the expulsion of the Arab population.”

Lebovic describes the third sub-school—cultural Zionism—as “a peaceful, peacenik attempt to bring back Jews collectively to Palestine on a confederative basis, with a binational parliament giving equality to the Zionists and to the Palestinian people.”

Zarchi, says Lebovic, advocated a blend of cultural and political Zionism and criticized the treatment of Arabs by Jews and more so by the British.

“Zarchi was very critical of any form of colonialism, especially British colonialism and those British colonial elements that transferred to political Zionism,” says Lebovic. “In 1946 he wrote a novel, And the Oil Streams Flow into the Mediterranean, that showed how colonialism robbed the indigenous population of its natural habitat and resources.

“The critics were really baffled by this novel; they didn’t understand what Zarchi was trying to achieve. I think Zarchi had a sense of the paradigmatic change—political and economic—that was about to occur. He foresaw the change as clearly or more so than the politicians of the time.”

Like Lebovic, who speaks Hebrew, German and English, Zarchi was a polyglot. He wrote in Polish, German and Hebrew, and he translated literary works from German and English to Hebrew.

Toward the end of his life, Zarchi battled both depression and cancer. But his final novel, which was published posthumously, ends optimistically, Lebovic says. It follows a group of Jews emigrating from Yemen who choose to live a life of “pseudo-mythological conditions” in Palestine.

“Their attitude was ‘love your stories, not your life; live the life of literary figures, not your actual life.’ According to Zarchi, Yemenite Jews never assimilated to secular Zionism…They kept their distinct mythology and their own folklore. For Zarchi, this opened up a new way to thinking about existence as a whole—you can live in your own literary mind.”

Lebovic’s first book, The Philosophy of Life and Death: Ludwig Klages and the Rise of a Nazi Biopolitics, explored the work of the 20th-century German philosopher and was well-received by critics in the United Kingdom, the United States and Germany.

“Lebovic convincingly shows the complexity of Klages’s work,” wrote The American Historical Review, “and even more importantly the complexity of the intellectual landscape in which it was situated.”

Story by Kurt Pfitzer

Posted on: