A transformative experience

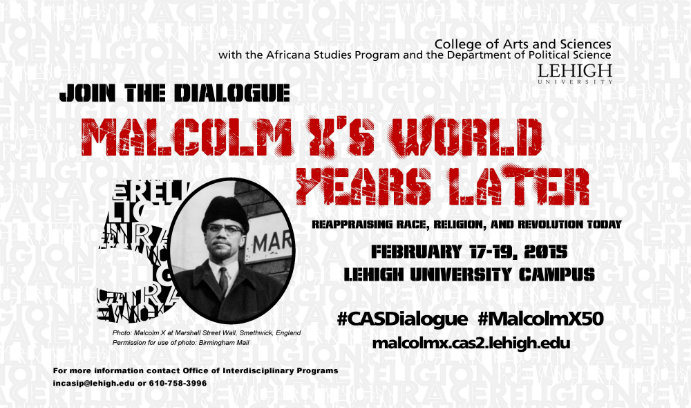

For three days last week, internationally renowned scholars and activists examined the life and legacy of Malcolm X. “Malcolm X’s World 50 Years Later: Reappraising Race, Religion and Revolution Today,” hosted by Lehigh’s College of Arts and Sciences, the Africana Studies program and the political science department, commemorated the 50th anniversary of the human rights activist’s assassination and provided an opportunity for meaningful dialogue.

The conference’s final panel featured the reflections of Lehigh faculty on both Malcolm X and the conference held in his honor.

Donald Hall, dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, thanked the panelists and conference participants.

“Who could have imagined a better exchange than what we had here? Certainly a conference is only successful if participants join in the dialogue that our College of Arts and Sciences exemplifies, and the discussions that took place over the course of the past three days have certainly been thought-provoking and enlightening. Your participation was the lifeblood of the conference,” Hall said.

Saladin Ambar, associate professor of political science, conference co-chair and author of Malcolm X at Oxford Union: Racial Politics in a Global Era, discussed the role of Malcolm X’s legacy today.

“Malcolm X was a spokesperson for the underground, a spokesperson for people from below,” he said. “We need to figure out how to honor that but also recognize who those spokespersons may be in our own time … As Malcolm X was misunderstood in his own time, who are we misunderstanding now? Who is speaking in that same voice—although in our time—in this new century?”

Ambar reflected upon the impact of Malcolm X’s life and death on leadership and the state of political movements today.

“In many ways, Malcolm’s death—along with later the assassinations of King, RFK, the Black Panthers, and so many Latin American, Asian and African heads of state, by covert and not-so-covert means—are all signifiers of a world in which a certain kind of leadership was to be denied,” he said. “And I think what that says to me is in many ways, Malcolm’s murder was tantamount to the beginning of a kind of leaderless movement that we’ve been in … I think what Malcolm’s death suggests to us is how we all have to identify our own—quoting [historian and activist Tariq] Ali— ‘authentic revolutionary’ spirit, and become self-actualized players in this drama called the struggle for human dignity.”

Standing in front of two projected images—the first of Malcolm X beside a photograph of a slain black man on a Los Angeles street in 1962 and the second of the body of Michael Brown on a Ferguson, MO street in 2014—Amardeep Singh, associate professor of English, described an event chronicled in Manning Marable’s book, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention.

In a disputed incident outside a Los Angeles mosque in April 1962, seven unarmed members of the Nation of Islam were shot by Los Angeles police officers. Ronald Stokes, a friend of Malcolm X, was killed. Stokes reportedly had his hands up and was shot in the back.

Malcolm X’s response to Stokes’ death, Singh said, was “an unusual, if not singular event:” He solicited volunteers to exact revenge for the killing by assassinating LAPD officers.

“[This] reminds us that Malcolm X, who so powerfully and memorably gave a voice to black anger and alienation, was also subject to human fallibility. In a moment of passion and anger he asked his followers to do something that was out of character and may have diminished his legacy.”

However, Elijah Muhammad, the leader of the Nation of Islam, instructed Malcolm to stand down. Malcolm complied, but this marked his increasing commitment to “the idea that the way forward for the black community was going to be through struggle [and] through civil rights activism.”

“The uncanny parallels between what happened to Ronald Stokes and what happened to Michael Brown—down to the non-indictment of the police officers involved—reminds us that the police relationship with the black community hasn’t really changed. Excessive and unwarranted police violence is still very much with us, the bodies of young black men are still on the pavement, we’re still watching and looking at their photographs, frustrated that justice is not being done,” Singh said.

Monica Miller, assistant professor of religion and Africana studies, described the relationship between Malcolm X’s legacy and hip hop as especially important for a generation that doesn’t necessarily read autobiographies.

“In thinking about the legacy of Malcolm on hip hop, I can’t help but to actually focus on the opposite. That is, what is the legacy of hip hop on how Malcolm X is learned in that historical remaking of Malcolm? [Many people] learn about Malcolm and many great others through hip hop,” Miller said.

“This thing called historical memory becomes a remix and a kind of reevaluation of what notions of freedom, truth, independence, and social action and political imagining look like for the current historical moment. Hip hop, in my opinion, especially for many youth disconnected from history but yet victims of history, keeps history in all of its complexities alive and well and culturally specific. Hip hop’s legacy for a wide variety of communities helps us to navigate the world and make sense of who we are through a certain kind of selective remembering and a selective strategic forgetting … Hip hop, much like Malcolm X and others, finds unique and brilliant ways to underscore the nightmare through the hopes and the dreams.”

James Peterson, associate professor of English and event co-chair, also addressed the role of Malcolm X’s legacy in hip hop culture.

“The autobiography of Malcolm X shapes rap music in many, many different ways. Rap music doesn’t just sample the content of Malcolm X’s speeches, it’s also deeply invested in the form of the autobiographical narrative itself … What Malcolm X does for hip hop culture is he functions as an engine through which the music continues to be important to the African American community and to the global community that listens to it,” Peterson said.

Peterson closed with some thoughts about the conference and its impact on Lehigh, noting in particular a conference presentation by Kashi Johnson, associate professor of theatre and Africana studies, and Darius Omar Williams, assistant professor of theatre and Africana studies.

“[To] walk into the space and see [Johnson and Williams] in the front exchanging poetic lyrics and powerful ruminations on ideas central to the themes of this conference was one of the most moving moments in the conference, but being in that space was really powerful for me as well because I realized that they had transformed the space,” Peterson said.

“We have world-class scholars here and people doing all kinds of incredible work around Malcolm X, but that moment for me was yet another highlight, a powerful sort of testament to the ways in which artistry and activism and critical work can all come together in the same space and be transformative for our community.”

Story by Kelly Hochbein

Posted on: