Lehigh and China: The Untold Story

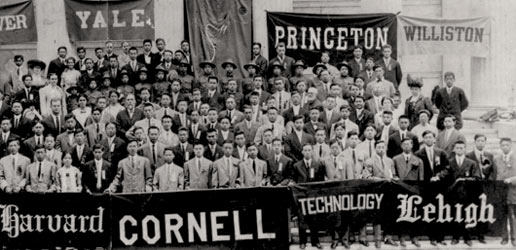

A gathering of the first Chinese Students Club of Lehigh University, founded in 1909. Lehigh President Harry S. Drinker, seated, was named an honorary member.

Tiedan Huang weaved her way through a small crowd of students, staff, and faculty peering into glass cases in the lobby of Fairchild-Martindale Library. She paused at a small black-and-white photograph that caught her eye.

I had no idea he went to Lehigh, said Huang, surprised to discover a recognizable name.

The photograph that caught her attention was of Ho Chieh, a 1914 Lehigh graduate student who went on to direct the department of Geology at Peking University, one of the first departments of modern geology in China.

Through a collection of images alongside Chieh's photo, the historic ties between Lehigh and China began to unfold. Each display case in Fairchild-Martindale contained images and biographies of Chinese pioneers of railroad engineering, astronomy, and geology-all of whom had studied at Lehigh beginning in the late 19th century.

These people made significant contributions to China's industry and also to many academic disciplinary areas, said Huang, a doctoral candidate in educational leadership and a native of China.

The exhibit kicked off the start of a celebration of the long-standing relationship between Lehigh and China, which marked its 130th anniversary during the 2009-10 academic year. Uncovering this relationship has become a personal passion for Dong-Ning Wang '98 Ph.D., who has been researching this facet of Lehigh history for nearly three years.

Early Days of Study Abroad

In the summer of 2007, a doctoral candidate at Cambridge University e-mailed Wang requesting information on two Lehigh students who were funded by China's first iron and steel company, Han Yeh Ping, at the beginning of the 20th century.

With the help of Ilhan Citak, Lehigh's librarian of archives and special collections, Wang located the students in student directories from 1918 through 1929 along with 10 other Chinese students likely sponsored by Hanyeh Ping.

We're not clear how they are connected with Lehigh or who sent them, Wang said, but their presence at Lehigh sparked her curiosity.

Wang began working at the Compound Semiconductor lab in 2004. In 2007, while working as an application engineer, Wang also served as a visiting scientist with Michael Notis, now professor emeritus of materials science and engineering, on several projects examining ancient artifacts.

Later that summer, Wang came across a Chinese documentary, titled You Tong (Little Kids), which retold the story of China's first study abroad program. Intrigued, she bought both the book and its associated film.

The documentary chronicled the lives of 120 boys, who were around 12 years old in 1872 when the Qing government sent them to preparatory schools in the Connecticut River Valley area. The students attended American high schools and entered college, but their studies were abruptly curtailed in 1881 after relations between China and the United States deteriorated. Before returning to China, the students enrolled at prestigious colleges, such as Harvard, Yale, Cornell-and Lehigh, which had been founded only 14 years earlier.

You Tong mentioned that at least one Chinese student enrolled at Lehigh in 1879, but more might have come. At that point, my heart started pumping, Wang says and she remembers thinking, This is something I need to look into.

Wang returned again to Lehigh's special collections, where she found a directory indexing every student enrolled in Lehigh until 1879. The list included not one but five students who matriculated in 1879 and cited their homeland as China. Looking at their names, Wang realized that she had found her next research project, a project her mentor, Notis, began 30 years earlier.

A Door Opens

In 1949, the People's Republic of China rose to power, formed a partnership with the Soviet Union, and severed all relations with the U.S. and other Western Nations.

Almost 30 years later, in 1978, a new era in U.S.-Chinese relations dawned, when Deng Xiaoping, the de facto leader of China, declared an open-door policy with the West. Although the policy was primarily an economic agreement, it also applied to academic institutions.

In 1979, Notis traveled to Beijing to present a lecture on ancient Asian metallurgy at the Beijing University of Iron and Steel Technology. He returned three times to speak at the beginning of the Use of Metal and alloys Conferences, the first of which was held in 1981.

While he was overseas, Notis met with several members of the active Lehigh University alumni Club in China. In 1986, his curiosity in technical history led him to research the contributions of Lehigh University's alumni to Chinese metallurgy. Through his queries, he discovered Jin Wang '15, a chemical engineering major.

After graduation, Jin Wang (no relation to Dong-Ning Wang) achieved renown as a scientist in China, where he served as dean at two major universities: the College of Sciences at Southeast University and National Central University in Nanjing. He developed China's first analytical chemistry lab, founded several Chinese scientific societies, and was editor-in-chief of China's research journal, which is equivalent to Science or Nature.

Although Jin Wang had died before Notis learned of him, Notis met and interviewed his nephew, sister, and brother-in-law. Videotapes of Notis' interviews include discussions on Jin Wang's life at Lehigh, his courses, his work in chemistry, and even his religion, which mingled elements of Confucianism, Buddhism, Protestantism, and Judaism.

Two years ago, Notis gave Wang the filmed interviews and related materials he collected. In December, Wang also met with Jin Wang's nephew, who is also a well-known scholar in China, and further inquired about his uncle's achievements and how Jin Wang's education shaped his choices.

Dong-Ning Wang has uncovered other alumni of renown, including an alumnus who led China's railroad industry, rose to a high position in China's government, and was appointed as a diplomat. Another built China's first observatory and a planet was named in his honor. One alumnus, Shengbai Cai, was one of the most successful entrepreneurs of the Chinese textile industry in the early 20th century and was known as the King of Silk.

Lehigh has so many tremendous contributions to modern Chinese history. We don't know about it. That's really amazing to me, Wang says.

Research at Lehigh

Wang, who still conducts materials research at Lehigh, has been working to uncover and publicize the role Lehigh's alumni played in Chinese history and technical development. She is assisted by a group of 10 to 15 volunteers, most of whom are graduate students from China.

The team is unraveling the lives of Lehigh's oldest Chinese alumni by painstakingly translating texts, comparing dates and names, and combing through copious historical documents. The graduate students are not historians. They spend most of their days, and often nights, in engineering and physics laboratories, and yet they devote four to eight hours a week to Wang's project. Their only recompense is pizza, the occasional Chinese meal, and the satisfaction of knowing that they are helping Wang and bolstering Lehigh's reputation in their hometowns.

We're going to get a Ph.D. from Lehigh anyway, so we hope this university will be more famous in China, explains Cheng Chen, a doctoral candidate in electrical engineering.

Jie Deng '09 Ph.D. also conducted research during his time at Lehigh. He related to the alumnus he researched, Zhong Liang Huang, who was one of the Chinese students dispatched by the Qing government. Although he never graduated, Huang became one of China's foremost engineers, attaining a high position in the country's largest mining company and directing China's railroad construction. He later accepted a position of diplomat to San Francisco, Calif.

I didn't sail for one month, like he did. I took a flight for 14 hours, Deng says. Still, there's some common sharing of experience. We both went into a new culture and had culture shock, and we had to learn advanced technology.

Huang's story could not have been retold until recently. Such research had been barricaded by the Chinese government's heavy restrictions on historical documents, but new standards of transparency have granted Wang access to fresh information.

Although reduced restrictions revealed many connections between Lehigh and China, the researchers have encountered unforeseen obstacles, including issues with the translation of Chinese characters and multiple spellings of surnames.

In addition, many of the educated Chinese had 'style' names as well as given names, which could be transliterated in several different ways depending on the person's native dialect, says Constance Cook, professor of Chinese and one of five project investigators for Lehigh's Chinese bridge Project.

Despite these difficulties, Wang and her fellow researchers discovered enough information on Lehigh's well-known Chinese alumni to provide biographical sketches on a Web site, which they continue to expand.

A Leader in Global Relations

The biographical sketches represent only half the story. The researchers must also discover why the earliest Chinese students selected a fledgling university instead of more well-established institutions such as Yale.

We have no idea why the very first students came, Wang says. She hopes to find leads in a collection of donated books found in a library in Rhode Island.

The researchers do have some hunches as to why Chinese students attended Lehigh at the turn of the 20th century. Notis theorizes that Lehigh's mining engineering program drew students hoping to enter China's expanding mining operations. As evidence, he cites the large proportion of Lehigh's Chinese alumni who entered the iron and coal industry.

Lehigh's facilities and location at the time-near Bethlehem Steel and Pennsylvania coal mines-gave it an advantage over other engineering schools. The 1912 edition of the Bulletin of the American Institute of Mining Engineers describes in elaborate detail Coxe Mining Laboratory and Fritz Engineering Laboratory's top-of-the-line mining and milling equipment. It concludes, Lehigh has commonly been regarded as a coal-mining school; [sic] but the present equipment places it among those schools which also emphasize the metal side of the mining industry.

The facilities were built under the watch of Henry drinker 1871, Lehigh's fifth president, and the first Lehigh graduate with a degree in mining engineering. Drinker also helped found the Chinese student club in 1909, believed to be the first Chinese student club in the U.S. Last year marked the 100th anniversary of the club.

Notis suspects that drinker might have had a more active role in bringing Chinese students to Lehigh during his tenure from 1905 to 1920. Drinker's parents were missionaries in Hong Kong, where he lived for seven years and learned Chinese. I cannot imagine anything [of this magnitude] at Lehigh taking place without the university's president signing off on it, Notis says.

Lehigh has been a leader in global relations since the very beginning, Wang says.

Chinese students continued to enroll at Lehigh after Drinker's tenure. Although political disagreements between the People's Republic of China and the U.S. barred Chinese students from entering the U.S. for 30 years, they have returned to Lehigh since the open door policy was instituted in 1978. Today, 250 Lehigh students-more than half of Lehigh's international students-come from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. In fact, about 98,000 Chinese students are studying at U.S. colleges and universities today.

Wang's research provides these students a sense of belonging at Lehigh and the knowledge that others from their land have also passed through some of the same hallways. In addition, her discoveries have sparked conversations with people from universities in China. These conversations may generate greater Chinese interest in Lehigh, while opening more ways for Lehigh students to spend time in Asia.

If you build a bridge from Lehigh to China to connect past and current students and actively bring them together-that would be a significant impact, don't you think? That's what I'm trying to do, says Wang.

Bridging History and Culture

As Wang continues to construct her theoretical bridge, a related project is underway at Lehigh that will honor this heritage and strengthen the existing ties between the university and China. Dubbed the Chinese bridge Project, the program will draw from the university's three undergraduate colleges to bridge cultures and disciplines through a major academic effort.

A $300,000 grant from the Henry Luce Foundation is helping to bolster the Asian Studies program at the university and cultivate a cohort of students who will gain a significant understanding of the language, history, and culture of one of the world's most influential nations.

New courses from the Asian Studies program began this spring, including Explorations in the History of Science and Technology in China and Survival Chinese, which provides a basic understanding of the Chinese language. An intensive East/West design work shop will be taught in 2011 by Anthony Viscardi, professor of architecture.

Wang and Norman Girardot, religion studies professor, both project investigators for the Chinese bridge Project, are instructing a digital bridges course that expands the Web site that honors the Lehigh-Chinese heritage as well as documents and films the progression of the project.

The Chinese bridge Project cohort will also have the opportunity to immerse themselves in Chinese culture this summer. The annual Lehigh in Shanghai program will be adapted to offer students an intensive program on Chinese language and culture, followed by a four-week series of workshops in which they'll begin to develop an understanding of bridge building as well as the historic significance of Chinese science and technology. The students will participate in a specially designed summer session at Tongji University in Shanghai and the University of Science and Technology Beijing.

The Chinese bridge Project will extend a time-honored tradition of global inquiry and cultural exchange between China and Lehigh that began in the early 20th century and continues with students like doctoral candidate Tiedan Huang.

In China, says Huang, we have this saying: History is the mirror. If you don't look back into history, you don't know the glory and the sorrows. And this is the glory.

Posted on: